![]() Neal Carter (14 Dec 1902 – 15 Mar 1978) was a mountaineer and early explorer of the Coast Mountains primarily in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Highly skilled as a mountaineer, Carter also excelled at cartography and surveying which he used to map the vast unnamed and unexplored mountains of BC. He named a staggering number of mountains, peaks and glaciers as well as making 25 first ascents of mountains, many of which surround what we now call the Whistler Valley.

Neal Carter (14 Dec 1902 – 15 Mar 1978) was a mountaineer and early explorer of the Coast Mountains primarily in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Highly skilled as a mountaineer, Carter also excelled at cartography and surveying which he used to map the vast unnamed and unexplored mountains of BC. He named a staggering number of mountains, peaks and glaciers as well as making 25 first ascents of mountains, many of which surround what we now call the Whistler Valley.

Neal Carter Mountaineer

- Neal Carter Mountaineering Highlights

- First Ascents by Neal Carter

- 1920: Black Tusk North Pinnacle

- 1922: Second Ascent of The Table

- 1923: Carter/Townsend Expedition

- 1932: Mount Meager Expedition

- 1933: To the Cradle of Toba River!

- 1934: Mount Waddington Tragedy

Carter recalled his first impression when he first saw it in 1923, “..the skylines seen from their main valley in which Alpha, Nita, Alta, and Green Lakes lie. Alpine features beyond those skylines were pretty sketchy on maps, and few had names.” A few weeks later he and Charles Townsend would spend two weeks exploring these mountains, nearly all unclimbed, unnamed and very challenging. A skilled mountaineer, surveyor and cartographer, he compiled much of the data that went into the first official topogra

1932: Meager Expedition

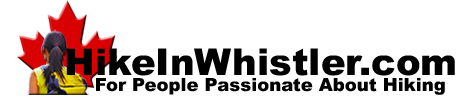

August 8th-20th, 1932 Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Mills Winram and Alec Dalgleish went on a spectacular mountaineering expedition up the headwaters of Lillooet River to Mount Meager. On day 5 Carter recalled, "the toe of a likely looking ridge at an elevation of 1750 feet opposite some hot springs on the bank of the creek was reached." The hot springs they saw are now well known as Meager Hot Springs. In the following days they climbed all six of the volcanic peaks of the Mount Meager massif and named the five unnamed ones. Mount Job, Capricorn Mountain, Devastator Peak, Plinth Peak and Pylon Peak were named. Beyond Meager, unknown peaks stretched to the ocean and another expedition was planned. Continued here...

1932: Mount Meager Expedition

Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram

1932: Mount Meager Expedition

Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram

The Mount Meager massif is a collection of volcanic peaks that can be seen in the distance, to the west of Pemberton Valley, 150 kilometres north of Vancouver. Mount Meager produced the largest volcanic eruption in Canada in the last 10000 years when it had a huge eruption 2400 years ago. In recent years it has produced another type of hazard, debris flows. The last one happened in 2010 when more than 48 million square metres of debris cascaded down from Capricorn Glacier. It was the largest debris flow ever to occur in Canada. In 1932 Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram went on a two week expedition into the mountains at the source of Lillooet River. Two years previously Tom Fyles caught a distant glimpse of the unexplored peaks from Gargoyle Peak. Fyles described the area of ice and snowfields far exceeding that of the Columbia Icefield. The 1932 expedition was photographed and Neal Carter wrote a detailed article, ‘Exploration in the Lillooet River Watershed’ in the 1932 edition of the Canadian Alpine Journal. This is the article Carter wrote which details their amazing journey into the unknown. Date headings in blue have been added for clarity. The black and white photos from the article have also been added and some have been colorized a little or a lot.

EXPLORATION IN THE LILLOOET RIVER WATERSHED

By NEAL M. CARTER

That section of the British Columbia Coast range of mountains which covers the 1500 square miles between latitudes 50°30’-51°00” and longitudes 123°30°-124°30° is practically unknown from a mountaineering standpoint. Large scale maps of the Coast utilize this area for title and legend, which, in an alpine region is a direct invitation for exploration.

Parties which have penetrated comparable watershed areas such as the Mt. Waddington district and the mountains north of Bute inlet have shown that such exploration is well rewarded by the finding of peaks of unexpected height and panoramas of snow and ice reminiscent of the last throes of an ice age. The possibility of similar surprises in the region just described seemed quite likely in view of the fact that it is known to feed four large glacial rivers; the Southgate flowing into Bute inlet, the Toba emptying into Toba inlet, the Lillooet which joins the lower Fraser River, and the Elaho, a main tributary of the Squamish flowing into Howe Sound.

Distant views of this region had been obtained by Mr. T. Fyles’ party which ascended Gargoyle Peak in 1930 and by Major F. V. Longstaff’s party when at the headwaters of the Bridge River. The latter reported that the area of ice and snowfields seen far exceeded that of the Columbia Icefield. Four members of the Club, Messrs. Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish, Mills Winram and the writer, discovered a fortnight of coincident holidays in August of this year and decided the occasion was opportune for investigating what lay behind this tantalizing skyline which all had seen from some angle or other.

August 8th, 1932 Day 1: Vancouver to Pemberton

Leaving Vancouver on the morning of August 8th, the ever pleasurable journey by boat to Squamish and past Garibaldi Park on the P.G.E. train brought us late that afternoon to Pemberton, where the railway crosses the Lillooet river. It was up this river that we had decided to journey in our effort to reconnoiter the high peaks on the watersheds at its source. Twelve miles upriver by auto left us at a farm near the edge of civilization, where we literally “hit the hay” for the night.

August 9th, 1932 Day 2: Bert Perkins

Next morning, we placed ourselves in the care of one Bert Perkins, trapper of marten and packer extraordinary. What Bert didn’t know about the river systems of this part of the country wasn’t worth knowing, but he confessed that neither he nor anyone else could state what lay above and between the Lillooet and Toba rivers. If we would point out where we wished to go, however, he promised to do his best to get his three horses and our packs as far up as possible, and he did!

For twenty more miles up the south side of the Lillooet River we travelled over trail, swamp, gravel bar and quicksand, stopping overnight at a small cabin near South creek. The Lillooet changes its course so frequently that settlement of its wide and fertile upper valley has been found impracticable, much to the sorrow of some who made the experiment. Near the confluence of several of its tributaries the main stream had shifted since Bert’s last visit and we were left to negotiate delightful beaver swamps and devil’s club thickets while he waded channels with the horses. Occasionally an ice-cold, raging torrent with its load of water-borne boulders would prove too much for us on foot and the pack-horses would be requisitioned as ferries. Because of the steep sides of the main valley, very little of the surrounding mountains could be seen; our attention being chiefly centered on two peaks which lay far up the valley in the approximate position given for Meager Mt., the only named mountain shown on Government maps of this vicinity.

Mills Winram, Alec Dalgleish, Tom Fyles and Neal Carter

August 10th, 1932 Day 3: Meager Creek

By three o’clock in the afternoon of August 10th we reached Bert’s winter trapping headquarters, a well-equipped cabin some two miles below the junction of Meager creek, or south fork of the Lillooet. Here, at an elevation of approximately 1200 feet we paused to take in our surroundings. A wonderful stand of huge red cedars made the area almost park-like, a pleasing variation of the succession of nondescript forest types we had encountered. Besides cedar, the Lillooet valley supports a certain amount of cottonwood, white pine, Douglas fir and hemlock; the undergrowth consisting chiefly of snow bush, elderberry, devil’s club, high bush cranberry and young willow and alder. At higher elevations the cotton-wood and cedar give way almost entirely to the amabilis and Douglas fir and hemlock, which in turn is replaced by the usual alpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) intermingled with wild rhododendron.

It was now necessary to decide from what direction we should approach our objective, tentatively chosen as the group of peaks lying between Meager creek and the Lillooet. Only by climbing to some vantage point could this question be settled. So up we went, taking only our sleeping bags and overnight provisions, after promising to return by ten o’clock the following morning to allow Bert to get us across Meager Creek before the afternoon high water. A steep ridge immediately behind the cabin provided good going and by 8 p.m. we crossed timberline at 6000 feet and made camp after a fashion.

August 11th, 1932 Day 4: Beyond Meager Creek

Early next morning Fyles and Dalgleish crossed a glacier and ascended an 8000-foot rocky peak, while Winram and myself remained on the lower ridge where we established the first camera station of the photographic survey which had been planned by the writer. Unfortunately, rising mists from the valleys obscured much of the view. The general direction of the higher mountains was ascertained, however, and after a headlong descent of the steep ridge we reached the cabin on time and were able to inform Bert that our route appeared to lie up Meager Creek. That afternoon the southeast bank of the creek was followed until a cut-bank forced a crossing. The horses experienced considerable difficulty in finding a footing among the rolling boulders of the stream bed and we had some misgivings as to the condition of the river on our return, should the weather clear up and become hot. Bert’s little dog “Scotty” which we had met at the cabin got left behind here, since he refused to swim the torrent and the horses were not equal to an extra return trip for him. Some three miles up the creek, camp was pitched for the night.

Crossing Meager Creek - 11 August 1932

August 12th, 1932 Day 5: Hot Springs

On the morning of August 12th, the toe of a likely looking ridge at an elevation of 1750 feet opposite some hot springs on the bank of the creek was reached. Here we expected Bert would leave us with his blessing, to return six days later. But not Bert. He disappeared for a while and returned with the news that he thought he could get the horses up that ridge. It was a mighty task; but windfalls, hornets, rhododendron bush and rock slides were slowly left behind (except in the case of the hornets) and a camp finally established on a flower strewn bench just at timberline (5665 feet).

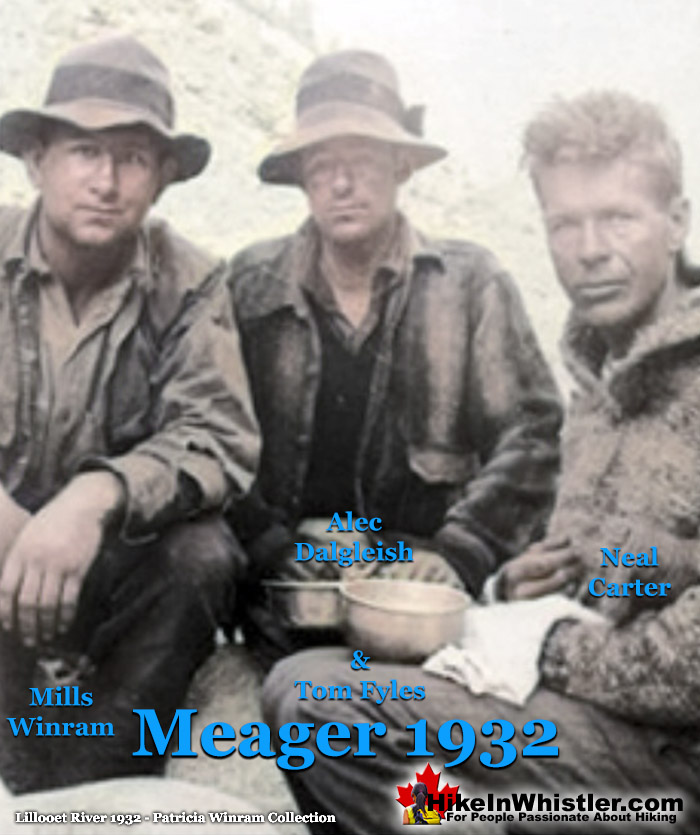

August 13th, 1932 Day 6: Mt Capricorn

The weather for our first climbing day was disappointing and only four days’ climbing was available. With no definite knowledge of how our ridge was connected with the high peaks we had seen two days previously, we decided to tackle the foggy heights immediately behind camp. The ridge grew more arête-like and on a sharp pinnacle of rock we halted for a bite to eat at 7850 feet, hoping the fog might lift. When it eventually did, pinnacle after pinnacle appeared dimly before us, each higher than the last, until we wondered when the procession would cease. It was soon evident that we had chosen the wrong approach to the high, rocky pyramid in which our ridge culminated, so retracing our steps we descended to a glacier below and skirted the base of the ridge. This glacier proved most tractable in providing a fine crevasse-free bench which was to become a necessary matutinal and evening promenade each day as the easiest route to the mountains beyond.

Projecting from a snowy dome at the head of the glacier was a most startling series of grotesque pinnacles of rock. Here we spent an hour waiting for the fog to lift, climbing the more solid towers and inspecting three remarkable rock “windows” which pierced the base of one mass. We named this group “The Marionettes” from their diversity of form. The generally volcanic nature of the region justifies the belief that they are the remains of a volcanic rim, a most interesting vertical section through breccia, basalt and fused ash containing nodules of banded quartz being visible.

The fog had now lifted but the dullness of the day did not encourage an attempt on the rocky peak which rose above us, accessible apparently only by means of a steep snow couloir. We accordingly descended 700 feet to a snow pass and made the first ascent of an easy, snowcapped summit which gave us our first glimpses of the lay of the land. Swirling clouds discouraged a prolonged stay and we left the summit confident that we now knew how to best utilize our three remaining climbing days. The name chosen later for this 8440-foot mountain was Mt. Capricorn, a variation of the all-too-common appellation “Goat” applied by Bert to the stream which drains the Capricorn glacier at its base. A lusty shout before commencing an exhilarating 500-foot glissade down a snow bank just behind camp informed Bert that it was time to put on the kettle, and we retired to the accompaniment of pattering raindrops.

Neal Carter on Capricorn Summit Surveying - 13 August 1932

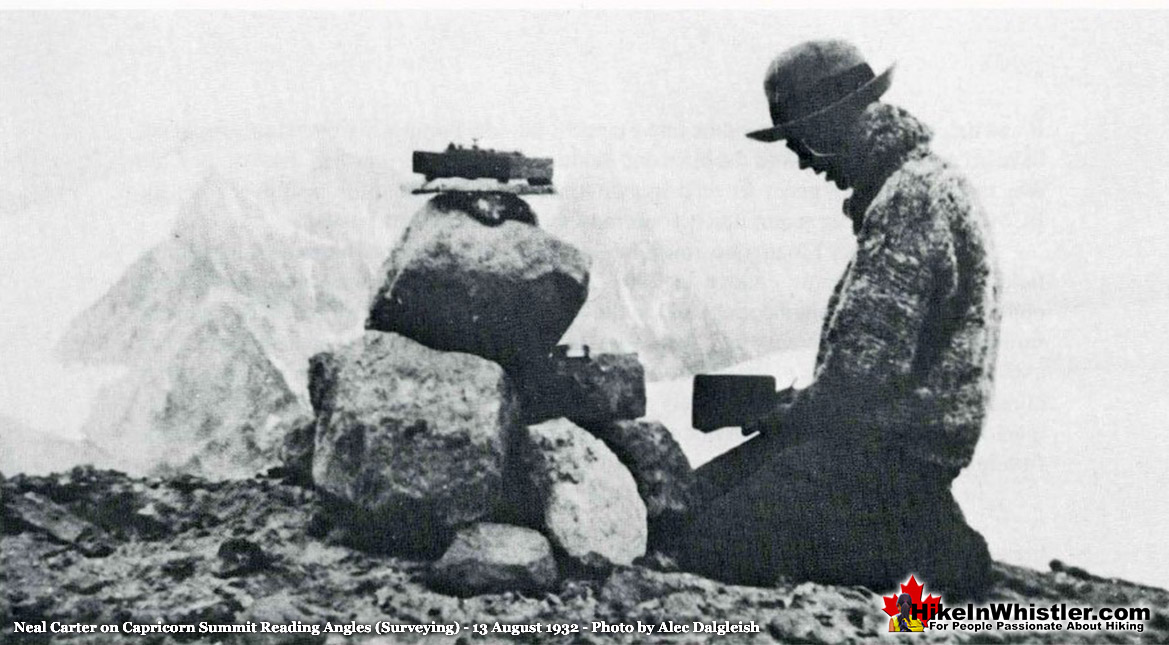

August 14th, 1932 Day 7: Plinth, Perkins Pillar and Meager

August 14th dawned most promisingly and we decided to bag the highest peaks seen close at hand yesterday. Following our return footsteps of the previous evening as far as the base of Mt. Capricorn, we swung to the right and ascended the Capricorn glacier to a peculiar, three-way pass below what we believed to be the aforementioned Meager Mt. This pass, named Triskelion after the device on the Manx coat-of-arms, provided a close up view of a sheer, 400-foot rock pillar which had been observed by different trappers from the Lillooet valley. At Bert’s request its height was triangulated in order to settle a (financial?) argument which appears to have originated between him and some of his pals. “Perkins’ Pillar” seemed a good name.

Meager Mountain & Perkins Pillar - 14 August 1932

Turning now to the supposed Meager Mt., we found its ascent relatively simple except for the last hundred feet. The loose, igneous rock, brightly colored in hues of red and sulphur-yellow, proved most treacherous and we rested on an ashy saddle just below the summit, where a Lapland longspur graced us with its company. An interesting feature of the view from here was an outlier surmounted by two pointed pillars of rock strongly reminiscent of the well-known horns of the dilemma. One of these pillars was pierced by a “window” estimated to be twenty feet high, and which could be readily discerned from the valley below.

Tom Fyles on the Summit Ridge of Mount Meager - 14 August 1932

Fyles and Dalgleish went on to the final, tottering pile of rock which called itself a peak, but seemed hesitant about announcing their victory. They commenced throwing rocks at the blade-like crest of the ridge and triumphant shouts finally re-echoed their success in knocking over the unattainable summit, leaving them on the (now) 8830-foot peak of Meager Mt., one of the few recorded instances of the mountain coming to Mohammed. My effort to establish a camera station on the actual summit was unsuccessful since the necessary cairn would not stay poised. A small gap just below was finally utilized, and by pushing over several projecting masses with an ice-axe, most of the horizon could be photographed. Splendid views of the Lillooet valley and the mountains of the Bridge River district were obtained, but we were still at that edge of our little group farthest removed from the snowy giants to the west and northwest.

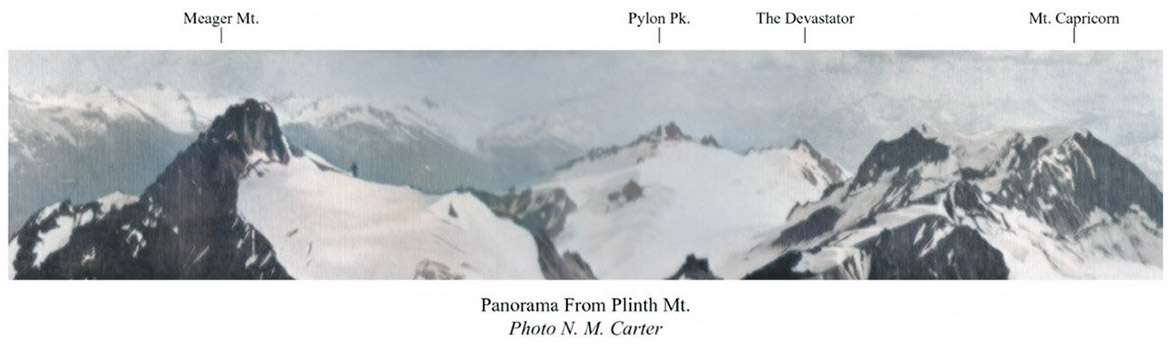

Just across one arm of Triskelion pass lay another peak which we had seen from the valley, and which now proved to be higher than our present viewpoint. Two hours later, after a final scramble up a shattered ridge thereby giving two goats a bad fright, we emerged on a flat, pumice-strewn summit which was the absolute antithesis of the one we had recently quitted. From four until six in the afternoon we tarried, sorting out the view and trying to recognize something on the horizon. An entirely unknown, heavily glaciated range over 9000 feet high lay some dozen miles to the west, behind which the tips of several peaks exceeding 10,000 feet in elevation could be distinguished. These lay in the direction of the headwaters of the Toba River and it was evident that they would have to be approached from that direction. Toward the southwest wave after wave of lower, entirely glacier-covered ridges culminated in some very high and sharp peaks which must lie some distance north of the head of Jervis inlet. Others at the head of Chilko Lake could be seen, but those few which possess names could not be identified with certainty. An angle read to one towering, cloud-capped giant far to the northwest disproved our supposition that it might be Mt. Waddington. Even the high summits near the head of Bute inlet known to Fyles and Dalgleish were apparently hidden.

The visibility was perfect and each of the party was quite familiar with the Coast range mountains, yet it was an eerie sensation not to be able to definitely recognize a single one of the sea of peaks extending over 180° of the horizon. Only to the east and south were old friends visible, where Mts. Cayley’ and Tantalus, together with various high summits in Garibaldi Park were visible. These mountains, 30-50 miles away, were the only reference points available for tying-in the survey. Later, during the plotting from the photographs, Mt. Albert (8260 feet) above Princess Louisa inlet was identified at a distance of 33 miles. An interesting feature of the immediate vicinity was the visible portion of the large glacier which forms the source of the Lillooet River. From its snout at an approximate elevation of 2500 feet, eight miles of this typical valley glacier was visible before it disappeared around a ridge in a westerly direction, where its shape suggested that it continues upward for several miles more. The only existing survey of the Lillooet River extended no further than Cypress creek which joins the river nine miles below the glacier, showing that the hypothetical western extension of the Lillooet River as shown on present maps is quite erroneous. It was with great reluctance that we were forced to leave our 8885-foot viewpoint, since named Plinth Mt. from its flat-topped, massive shape.

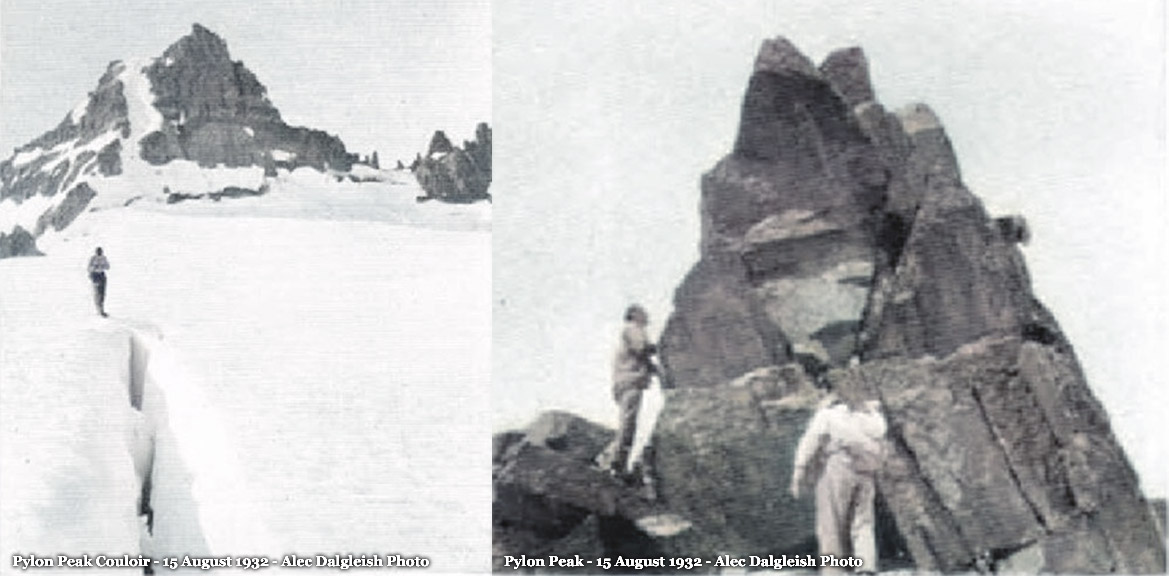

August 15th, 1932 Day 8: Pylon Peak

The third day of climbing saw us to the top of the rocky peak inadvertently attempted the first day. The steep couloir previously mentioned was negotiated with only one relief from the tedium of kicking steps. That was occasioned by a large boulder seeking a lower altitude via the same couloir. Once on the arête, a short rock climb led to the extremely satisfying summit composed of huge, angular blocks. Despite its lower altitude (8175 feet), this peak provided the best view yet obtained of the glaciated ranges lying across Meager Creek to the southeast, where several high mountains lay between us and Mt. Cayley. The entire drainage system of Meager creek was unraveled, as well as the watersheds and upper tributaries of the Elaho River. Pylon Peak seemed a fitting name for this rocky pyramid which has the most striking appearance of any mountain in the district.

Pylon Peak - 15 August 1932

Neal Carter and Tom Fyles Pylon Peak - 15 August 1932

The same afternoon a 7780-foot outlier of Pylon Pk. was ascended in order to ascertain the origin of a devastating flood which swept down Meager creek in October, 1931. Traces of its ravages had been evident as we travelled up the creek, and Bert recounted how he had witnessed from his cabin a succession of sudden floods passing down the Lillooet. The river rose many feet in a few minutes, was highly discolored, and bore many newly-uprooted trees. We discovered that a large portion of the volcanic ash and debris forming the flank of the summit on which we now stood had slid onto a glacier below which forms the source of one of the tributaries of Meager creek. The slide had apparently impounded the considerable surface drainage of the glacier, then giving way, had swept downstream. At each sharp bend in the valley great sections of the bank had been washed away and the amount of material deposited throughout the length of Meager Valley was enormous. Even the location and nature of the hot springs had been altered. Remains of the slide still buried the snout of the glacier which we named “Devastation glacier,” the peak above being dubbed “The Devastator.” The peculiar contrast between the extremely shattered, western portion of The Devastator and the firm, eastern summit composed of ancient rock bearing glacial furrows with a north-south trend gave indication of some intense, former stress. That night we sat around our camp fire under a full moon admiring a wonderful display of lightning taking place at the coast, 100 miles to the south. Each flash gave distinct silhouettes of mountains far down the Squamish valley which could not even be seen by daylight.

August 16th, 1932 Day 9: Job Mountain and Polychrome Ridge

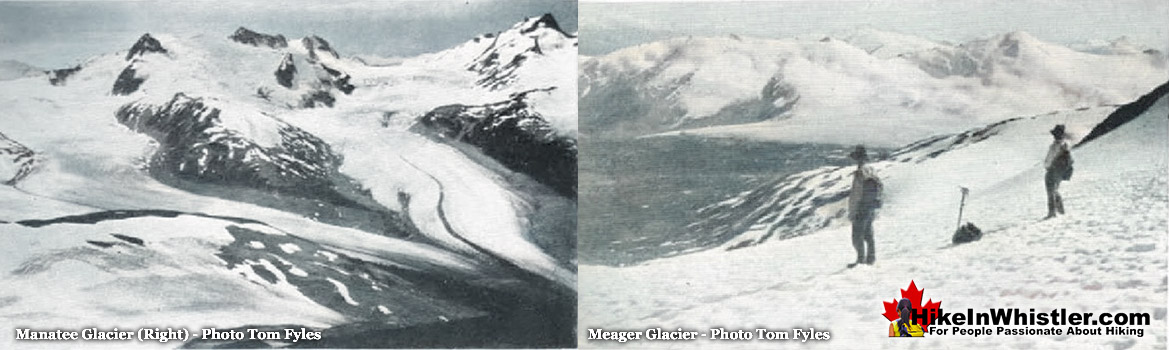

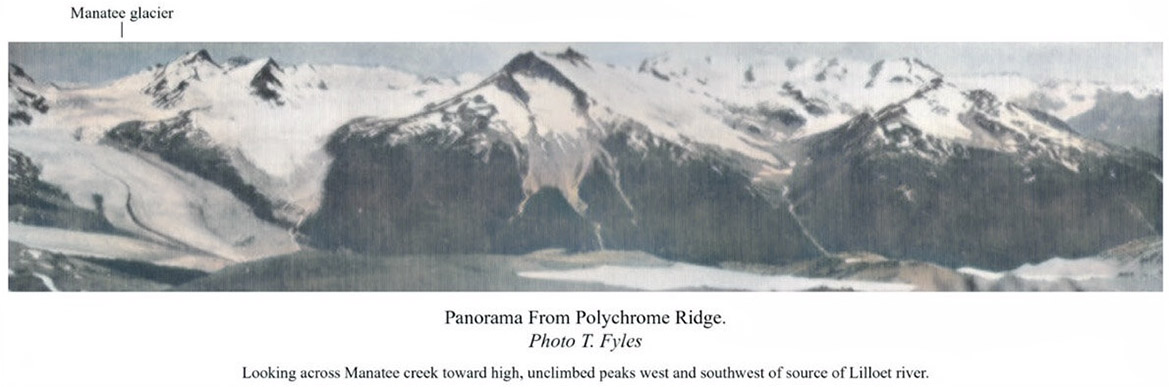

On our final day, three of us set off shortly after dawn to see how close we could approach one of the real high peaks seen toward the west. Traversing the now familiar route to the pass (7200 feet) below Mt. Capricorn, we struck off to the left and ascended the Devastation glacier, passing enroute an unclimbed volcanic pile which we termed Job Mt. because of the boil-like appearance of the innumerable protuberances of breccia on its sides. Around the rim of a large wind-cirque, over a flat outcrop of broken rock and down 1100 feet into a snow pass we travelled for miles with ever dwindling hopes. A half-hour after noon we topped an 8130-foot ridge composed of disintegrated fragments of multi-coloured, volcanic rock only to find that we were cut off from our objective by a valley far too deep to consider crossing.

Manatee Glacier Meager Glacier - 16 August 1932

We contented ourselves, therefore, with the close up view of the Promised Land and discussed ways and means of penetrating it from another direction some other year. To the south lay a large Icefield tumbling from a group of 9000-foot rocky peaks and terminating in a large glacier which spread out over a gentle divide. The tongue flowing east from the divide passes through an almost level, open valley and forms one source of Meager Creek, which immediately jumps over a high waterfall. In the valley are several small lakes, some of which are formed by the glacier (Meager Glacier) overriding the surrounding meadow. The tongue flowing west, after uniting with the Manatee glacier, so called because of a flipper-like process, dipped into the deep valley before us to form Manatee creek, the first southern tributary of the Lillooet River. Had we descended into the glacier pass, we might have had time to climb one of the lower peaks in the opposite range; the patience of Fyles and Dalgleish while I occupied myself for three hours with my instruments was commendable. I am sure they visualized themselves already part way up some mountain across the valley, but contented themselves with having explored practically all of our isolated little group. So we left “Polychrome Ridge” and wandered down its brightly colored rocks to the snow pass at the head of what was to become known as the Mosaic glacier. Then commenced the 1100-foot climb of the gentle snow slope of the opposite side, where we frequently paused to admire the gorgeous late afternoon coloring on the almost completely white southern horizon.

We varied our return route somewhat so as to traverse the névés of several small glaciers which flow toward the north to form tributaries of the Lillooet. “Job” and “Affliction” were names which suggested themselves for two of these, and later, when ascending the last, long slope leading up to the Marionettes, we encountered such numbers of ice worms that the name “Henlea” was chosen for this small glacier. Camp was reached just before dark and after supper, while quietly drinking in the smoke of our last high elevation camp fire, we listened to Winram’s and Bert’s tales of horse-fly swatting and goat hunting. Quite unsuspected by us, a hang-over of the previous evening’s thunderstorm cowardly crept up the Lillooet valley behind us and “let go” right above the tent (so it seemed). Actually, a tree was kindled on a ridge just across Meager Valley.

August 17th, 1932 Day 10: Meager Creek

We said adieu to the lupin and companionable little cottontops on the morning of the 17th and induced the horses to essay the downward plunge. Meager Creek was reached without mishap, but could not be crossed because of high water. Bert got almost half-way across at one point but nearly lost a horse in turning back. An hour after lunching on a gravel bar, the bar disappeared, and our equipment had to be moved twice before we felt safe for the night.

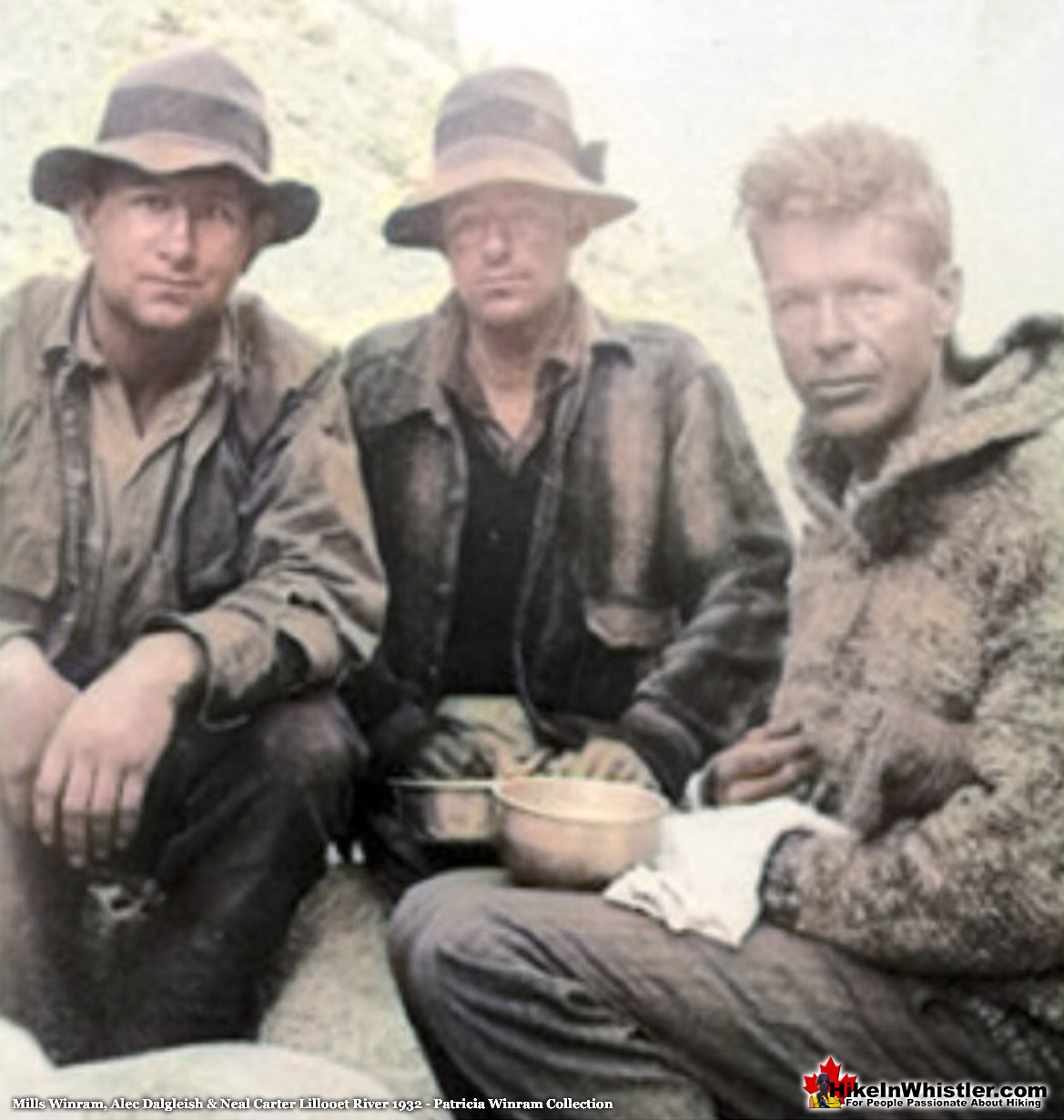

Mills Winram, Alec Dalgleish & Neal Carter Lillooet River - 1932

August 18th, 1932 Day 11: Hike to Bert's Cabin

Next morning, we crossed without much difficulty at a place where the stream had divided, and arrived at Bert’s cabin in time to have a much appreciated dip and shave followed by flapjacks and coffee ad lib. Shortly after leaving the cabin “Scotty” turned up on the trail after having apparently spent the intervening six days since his desertion in wandering up and down the trail trying to summon courage to swim either of the two streams which separated him from us and from home. We had one last unforgettable camp on the bank of the Lillooet where we could watch the shadows fall over Meager and Plinth, then the weather broke and...

August 19th, 1932 Day 12: Long Hike Out to Pemberton

...the next day was spent fighting wet devil’s club and soggy willow bottoms when we were not wading around trying to find a way from one gravel bar to the next. A disconsolate march through a mile of abandoned farm land (now flooded) left us in such a state that when we finally regained the first vestiges of a road with pole bridges, we had to restrain Winram from wallowing through the sloughs from force of habit.

August 20th, 1932 Day 13: Back to Vancouver

Another night in the hay loft and we were on our way home, thankful that we had been favored with the only good weather for weeks while “up above.” Subsequent working up of the photographs and information has resulted in a sketch map covering some 300 square miles of previously unmapped mountain territory. Several drainage systems have been elucidated and new approaches to the area indicated. The elevations given in this narrative are the averages of aneroid readings, to be considered as provisional pending the completion of a contoured map constructed from the photographs.