Hike in Whistler Glossary

Ablation Zones in Garibaldi Park, Whistler

![]() Ablation Zone: the lower altitude region of a glacier where there is a net loss of ice mass due to melting, sublimation, evaporation, ice calving or avalanche. The ablation zone of a glacier such as the Wedgemount Glacier has meltwater features such as englacial streams and a glacier window. An englacial stream refers to meltwater flowing inside a glacier. A glacier window is a cave-like opening at the mouth of a glacier where meltwater runs out. The ablation zone is located below the firn line. Firn originated from Swiss German and means "last year's snow". It has been compacted and recrystallized making it harder and more compact than snow, though less compact than glacial ice. A glacier such as the Wedgemount Glacier which stretches from Wedge Mountain down toward Wedgemount Lake, the ablation zone is very beautiful. A big pool of meltwater spills down the rock face and into turquoise coloured Wedgemount Lake. The pool of water is at the toe of Wedgemount Glacier and the large glacier window appears like a huge, gaping mouth. Big chunks of ice float in the pool and chunks of glacier split off into the water. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Ablation Zone continued...

Ablation Zone: the lower altitude region of a glacier where there is a net loss of ice mass due to melting, sublimation, evaporation, ice calving or avalanche. The ablation zone of a glacier such as the Wedgemount Glacier has meltwater features such as englacial streams and a glacier window. An englacial stream refers to meltwater flowing inside a glacier. A glacier window is a cave-like opening at the mouth of a glacier where meltwater runs out. The ablation zone is located below the firn line. Firn originated from Swiss German and means "last year's snow". It has been compacted and recrystallized making it harder and more compact than snow, though less compact than glacial ice. A glacier such as the Wedgemount Glacier which stretches from Wedge Mountain down toward Wedgemount Lake, the ablation zone is very beautiful. A big pool of meltwater spills down the rock face and into turquoise coloured Wedgemount Lake. The pool of water is at the toe of Wedgemount Glacier and the large glacier window appears like a huge, gaping mouth. Big chunks of ice float in the pool and chunks of glacier split off into the water. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Ablation Zone continued...

Accumulation Zones in Garibaldi Park, Whistler

![]() Accumulation Zone: the area where snow accumulations exceeds melt, located above the firn line. Snowfall accumulates faster than melting, evaporation and sublimation removes it. Glaciers can be shown simply as having two zones, the accumulation zone and the ablation zone. Separated by the glacier equilibrium line, these two zones comprise the areas of net annual gain and net annual loss of snow/ice on a glacier. The accumulation zone stretches from the higher elevations and pushes down, eventually reaching the ablation zone near the terminus of the glacier where the net loss of snow/ice exceeds the gain. The Wedgemount Glacier in Garibaldi Provincial Park in Whistler is an ideal place to see an accumulation zone up close. From across Wedgemount Lake you can see the overall picture of both the accumulation zone and ablation zone of a glacier. The Wedgemount Glacier is also relatively easy and safe to examine closely and hike onto. The left side of the glacier is frequented in the summer and fall months by experienced hikers on their way to Wedge Mountain and Mount Weart. Extreme caution is always needed and if you don't know how to remain safe while travelling on a glacier, you should avoid doing so. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Accumulation Zone continued...

Accumulation Zone: the area where snow accumulations exceeds melt, located above the firn line. Snowfall accumulates faster than melting, evaporation and sublimation removes it. Glaciers can be shown simply as having two zones, the accumulation zone and the ablation zone. Separated by the glacier equilibrium line, these two zones comprise the areas of net annual gain and net annual loss of snow/ice on a glacier. The accumulation zone stretches from the higher elevations and pushes down, eventually reaching the ablation zone near the terminus of the glacier where the net loss of snow/ice exceeds the gain. The Wedgemount Glacier in Garibaldi Provincial Park in Whistler is an ideal place to see an accumulation zone up close. From across Wedgemount Lake you can see the overall picture of both the accumulation zone and ablation zone of a glacier. The Wedgemount Glacier is also relatively easy and safe to examine closely and hike onto. The left side of the glacier is frequented in the summer and fall months by experienced hikers on their way to Wedge Mountain and Mount Weart. Extreme caution is always needed and if you don't know how to remain safe while travelling on a glacier, you should avoid doing so. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Accumulation Zone continued...

Adit Lakes in Garibaldi Park, Whistler

![]() Russet Lake sits in a wide, glacier carved valley at the base of The Fissile. In the direction opposite The Fissile, up on a plateau less than a kilometre away are two small tarns called Adit Lakes. Adit Lakes sit in a broad, boulder strewn alpine zone with an incredible view of Spearhead Range. Just a few metres from Adit Lakes the plateau drops off quickly into the huge valley that separates the Spearhead Range and Fitzsimmons Range. The Spearhead Range is named for its jagged array of spearhead shaped peaks that extend to include Blackcomb Mountain. Adit Lakes sit on a plateau in Fitzsimmons Range. From Adit Lakes you can look across the Musical Bumps all the way to the summit of Whistler Mountain. Musical Bumps is the collective name for the series of broad mountain peaks that have musical names. Viewed from Adit Lakes are Oboe Summit, Flute Summit and Piccolo Summit. The Singing Pass trail connects from the Musical Bumps trail and takes you down the valley between Whistler Mountain and Blackcomb Mountain to Whistler Village. The Singing Pass trail runs parallel to Fitzsimmons Creek which Adit Lakes drain into via Adit Creek. Fitzsimmons Creek is named after Jimmy Fitzsimmons who had a small cabin down in the valley near Fitzsimmons Creek. He was a miner that had a mining claim and hoped to find the other end of the copper vein that the Britannia Mine, opened in 1914, sat on. Adit Lakes are evidently named after the word miners use to describe a horizontal mine used to explore for mineral veins. The word adit comes from the latin aditus, which means entrance. Adits are dug into mountain ridges in the hopes of hitting the mineral vein or lode. Fitzsimmons was cutting adits here in the hopes of finding a vein of copper embedded between layers of rock. There are no visible traces of mining around Adit Lakes, but a few kilometres down the Singing Pass trail you can find remnants of old mine shafts. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Glossary: Adit Lakes continued...

Russet Lake sits in a wide, glacier carved valley at the base of The Fissile. In the direction opposite The Fissile, up on a plateau less than a kilometre away are two small tarns called Adit Lakes. Adit Lakes sit in a broad, boulder strewn alpine zone with an incredible view of Spearhead Range. Just a few metres from Adit Lakes the plateau drops off quickly into the huge valley that separates the Spearhead Range and Fitzsimmons Range. The Spearhead Range is named for its jagged array of spearhead shaped peaks that extend to include Blackcomb Mountain. Adit Lakes sit on a plateau in Fitzsimmons Range. From Adit Lakes you can look across the Musical Bumps all the way to the summit of Whistler Mountain. Musical Bumps is the collective name for the series of broad mountain peaks that have musical names. Viewed from Adit Lakes are Oboe Summit, Flute Summit and Piccolo Summit. The Singing Pass trail connects from the Musical Bumps trail and takes you down the valley between Whistler Mountain and Blackcomb Mountain to Whistler Village. The Singing Pass trail runs parallel to Fitzsimmons Creek which Adit Lakes drain into via Adit Creek. Fitzsimmons Creek is named after Jimmy Fitzsimmons who had a small cabin down in the valley near Fitzsimmons Creek. He was a miner that had a mining claim and hoped to find the other end of the copper vein that the Britannia Mine, opened in 1914, sat on. Adit Lakes are evidently named after the word miners use to describe a horizontal mine used to explore for mineral veins. The word adit comes from the latin aditus, which means entrance. Adits are dug into mountain ridges in the hopes of hitting the mineral vein or lode. Fitzsimmons was cutting adits here in the hopes of finding a vein of copper embedded between layers of rock. There are no visible traces of mining around Adit Lakes, but a few kilometres down the Singing Pass trail you can find remnants of old mine shafts. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Glossary: Adit Lakes continued...

Aiguilles in Garibaldi Park, Whistler

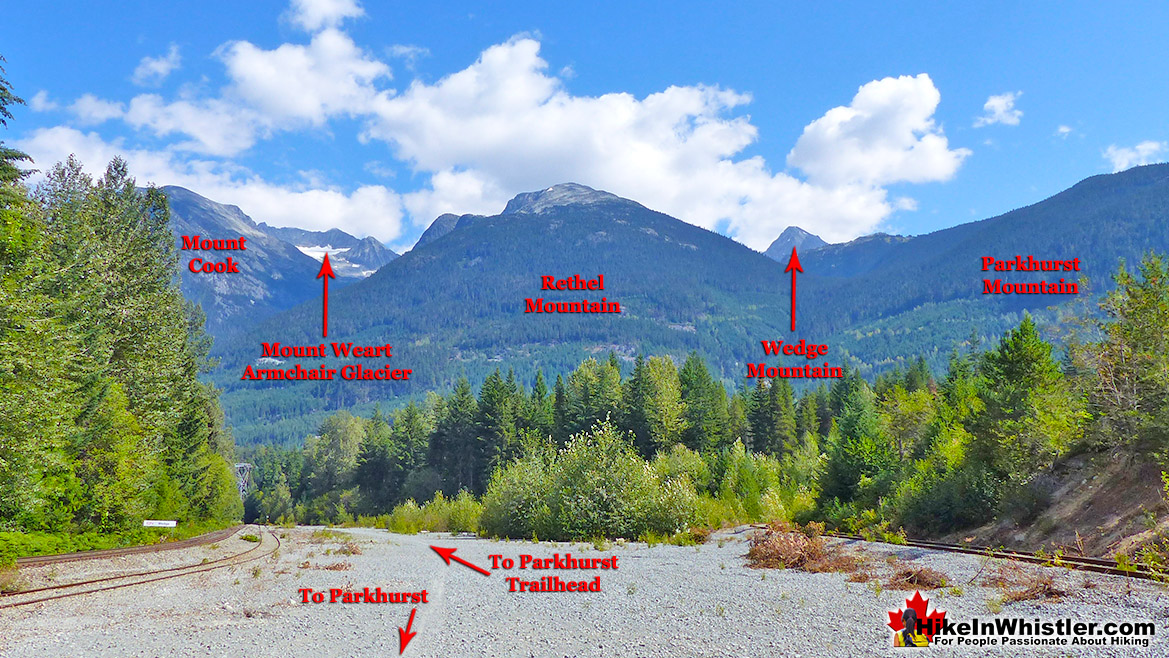

![]() Aiguille: a tall, narrow, characteristically distinct spire of rock. From the French word for "needle". Used extensively as part of the names for many peaks in the French Alps. Around Whistler and in Garibaldi Park you will find several distinct aiguilles. Shown here is the prominent aiguille that stands like a tower at the summit of Rethel Mountain above Wedgemount Lake. Standing near the hut at Wedgemount Lake, Rethel is the towering mountain directly across the lake. If you are looking at Wedge Mountain from Whistler Village, Rethel Mountain is the second mountain to the left of Wedge. In order they are Wedge Mountain, Parkhurst Mountain and Rethel Mountain. Parkhurst Mountain stretches down the valley to Parkhurst Ghost Town at the shore of Green Lake. Across Wedgemount Lake and still visible from Whistler are Mount Weart, Armchair Glacier and Cook Mountain. If you are new to Whistler and are unfamiliar with Wedge Mountain, it is the strikingly wedge-shaped mountain that dominates the skyline from many places in Whistler. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Aiguille continued...

Aiguille: a tall, narrow, characteristically distinct spire of rock. From the French word for "needle". Used extensively as part of the names for many peaks in the French Alps. Around Whistler and in Garibaldi Park you will find several distinct aiguilles. Shown here is the prominent aiguille that stands like a tower at the summit of Rethel Mountain above Wedgemount Lake. Standing near the hut at Wedgemount Lake, Rethel is the towering mountain directly across the lake. If you are looking at Wedge Mountain from Whistler Village, Rethel Mountain is the second mountain to the left of Wedge. In order they are Wedge Mountain, Parkhurst Mountain and Rethel Mountain. Parkhurst Mountain stretches down the valley to Parkhurst Ghost Town at the shore of Green Lake. Across Wedgemount Lake and still visible from Whistler are Mount Weart, Armchair Glacier and Cook Mountain. If you are new to Whistler and are unfamiliar with Wedge Mountain, it is the strikingly wedge-shaped mountain that dominates the skyline from many places in Whistler. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Aiguille continued...

Alpine Zones in Garibaldi Park, Whistler

![]() Alpine Zone or Alpine Tundra is the area above the treeline, often characterized by stunted, sparse forests of krummholz and pristine, turquoise lakes. Mount Sproatt is an excellent example of an alpine zone in Whistler. Dozens of alpine lakes, rugged and rocky terrain and hardy krummholz trees everywhere you look. The hostile, cold and windy climate in the alpine zones around Whistler make tree growth difficult. Added to that, the alpine areas are snow covered the majority of the year. Other good places to explore alpine zones in Whistler and Garibaldi Park are Wedgemount Lake, Blackcomb Mountain, Whistler Mountain, Black Tusk, Brandywine Meadows, Brew Lake, Callaghan Lake Provincial Park, and quite a lot more. Located within sight of Whistler Village, Wedge Mountain is the highest mountain in Garibaldi Provincial Park. Just a relatively short, 7 kilometre hike takes you to this mountain paradise of impossibly turquoise water and jagged mountain peaks all around. The shortness of the hike to Wedgemount Lake lulls hikers into thinking it is an easy trail. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Alpine Zone Continued...

Alpine Zone or Alpine Tundra is the area above the treeline, often characterized by stunted, sparse forests of krummholz and pristine, turquoise lakes. Mount Sproatt is an excellent example of an alpine zone in Whistler. Dozens of alpine lakes, rugged and rocky terrain and hardy krummholz trees everywhere you look. The hostile, cold and windy climate in the alpine zones around Whistler make tree growth difficult. Added to that, the alpine areas are snow covered the majority of the year. Other good places to explore alpine zones in Whistler and Garibaldi Park are Wedgemount Lake, Blackcomb Mountain, Whistler Mountain, Black Tusk, Brandywine Meadows, Brew Lake, Callaghan Lake Provincial Park, and quite a lot more. Located within sight of Whistler Village, Wedge Mountain is the highest mountain in Garibaldi Provincial Park. Just a relatively short, 7 kilometre hike takes you to this mountain paradise of impossibly turquoise water and jagged mountain peaks all around. The shortness of the hike to Wedgemount Lake lulls hikers into thinking it is an easy trail. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Alpine Zone Continued...

Arborlith and Lithophytes in Garibaldi Park, Whistler

![]() Every unusual phenomenon in the forest seems to have a name, but one natural work of art seems to be without a commonly used name. Big trees with sprawling roots that wrap around huge boulders, glacier erratics or jagged bedrock are sometimes called lithophytes which translates from Latin lith and phyte as stone and plant. Lithophyte is not the best description for these because they don't so much live on rock as encompass it. Lithophyte is widely used to refer to a plant that grows on or out of a rock, but doesn’t seem accurate to describe a tree that grows over and engulfs a rock. A lithophyte grows on solid rock or in the cracks of massive boulders and therefor survives on nutrients derived from these regions. The big trees in the forest we are talking about don’t survive on or in the rock itself, but rather treat it as an obstacle and grow mighty roots over, around and under it. Decades of water erosion may have washed away soil that once allowed a tree to grow on what now appears as solid rock. This seems to be the origin of the big western hemlock on the Cheakamus Lake trail that is growing on a house sized boulder that likely tumbled down from Whistler Mountain a century ago. One side of the boulder is mostly solid rock, whereas the side with the tree growing over it is disintegrating it into smaller boulders under the vice grip of roots and tremendous weight pressing down from above.

Every unusual phenomenon in the forest seems to have a name, but one natural work of art seems to be without a commonly used name. Big trees with sprawling roots that wrap around huge boulders, glacier erratics or jagged bedrock are sometimes called lithophytes which translates from Latin lith and phyte as stone and plant. Lithophyte is not the best description for these because they don't so much live on rock as encompass it. Lithophyte is widely used to refer to a plant that grows on or out of a rock, but doesn’t seem accurate to describe a tree that grows over and engulfs a rock. A lithophyte grows on solid rock or in the cracks of massive boulders and therefor survives on nutrients derived from these regions. The big trees in the forest we are talking about don’t survive on or in the rock itself, but rather treat it as an obstacle and grow mighty roots over, around and under it. Decades of water erosion may have washed away soil that once allowed a tree to grow on what now appears as solid rock. This seems to be the origin of the big western hemlock on the Cheakamus Lake trail that is growing on a house sized boulder that likely tumbled down from Whistler Mountain a century ago. One side of the boulder is mostly solid rock, whereas the side with the tree growing over it is disintegrating it into smaller boulders under the vice grip of roots and tremendous weight pressing down from above.

In other circumstances heavy snow of winter may bend a tree growing on a steep slope over a boulder for several years until it grows strong enough to resist the weight of snow and grow straight up. An excellent example of this can be found on the trail to Newt Lake in Whistler. In this case a fridge sized boulder on a hillside had a western hemlock crushed against it under snow for several years until it could resist the snow and grow upward. Now a decades old tree, it appears to be growing out of the middle of a big round boulder. Only when you walk around to look at it from the side do you notice the large tree trunk bending around the rock and into the ground. It doesn’t seem accurate to call either of these two trees lithophytes. As Steven Engelhart points out, “Lithophytes are plants that grown in or on rocks but most of these seem to take their nutrition from their immediate rock environment and not by extending their roots into the ground.” He suggest the word arborlith as a more accurate term for these amazing trees. Arbor is Latin for tree and lith translates as stone. Arborlith Lithophyte continued here...

Arêtes in Garibaldi Park, Whistler

![]() Arête: a thin ridge of rock formed by two glaciers parallel to each other. Sometimes formed from two cirques meeting. From the French for edge or ridge. Around Whistler and in Garibaldi Provincial Park you will see dozens of excellent examples. At the Wedge-Weart Col above and beyond Wedgemount Lake is a prominent arête that links these two of Garibaldi Park's highest mountains in. Wedge Mountain is 2892 metres(9488 feet) and Mount Weart is 2835 metres(9301 feet). Wedgemount Lake is one of the most spectacular hikes in Garibaldi Provincial Park. Though it is a relentlessly exhausting, steep hike, it is mercifully short at only 7 kilometres. The elevation gain in that short distance is over 1200 metres, which makes it a much steeper hike than most other Whistler hiking trails. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Arete Continued...

Arête: a thin ridge of rock formed by two glaciers parallel to each other. Sometimes formed from two cirques meeting. From the French for edge or ridge. Around Whistler and in Garibaldi Provincial Park you will see dozens of excellent examples. At the Wedge-Weart Col above and beyond Wedgemount Lake is a prominent arête that links these two of Garibaldi Park's highest mountains in. Wedge Mountain is 2892 metres(9488 feet) and Mount Weart is 2835 metres(9301 feet). Wedgemount Lake is one of the most spectacular hikes in Garibaldi Provincial Park. Though it is a relentlessly exhausting, steep hike, it is mercifully short at only 7 kilometres. The elevation gain in that short distance is over 1200 metres, which makes it a much steeper hike than most other Whistler hiking trails. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: Arete Continued...

A River Runs Through It

![]() Twentyone Mile Creek begins its long and steep journey from Rainbow Lake, high up and between Mount Sproatt and Rainbow Mountain. Cutting between the two mountains, Twentyone Mile Creek flattens out somewhat, passes under Alta Lake Road, then winds its way through a deep and dark forest before flowing into the River of Golden Dreams near the end of Lorimer Road. This hidden forest extends from Rainbow Park to Emerald Forest and between Alta Lake Road and the River of Golden Dreams. If you look closely at one of the parking lots in Rainbow Park, you will see a small trail sign for the wonderful trail that takes you through this secluded forest, all the way to Emerald Forest. A River Runs Through It is an insanely winding trail that follows a dizzying route through this captivating forest with Twentyone Mile Creek running through it. A popular, though brutally challenging bike trail, A River Runs Through It has numerous, elaborate ramps, small bridges, and one large bridge that spans Twentyone Mile Creek. A River Runs Through It has a couple shortcut trails that cut a couple kilometres off of it to make it a more manageable and enjoyable hiking trail. If you add in another two connecting trails, you can turn A River Runs Through It into a beautiful 6 kilometre circle route. ARRTI continued here...

Twentyone Mile Creek begins its long and steep journey from Rainbow Lake, high up and between Mount Sproatt and Rainbow Mountain. Cutting between the two mountains, Twentyone Mile Creek flattens out somewhat, passes under Alta Lake Road, then winds its way through a deep and dark forest before flowing into the River of Golden Dreams near the end of Lorimer Road. This hidden forest extends from Rainbow Park to Emerald Forest and between Alta Lake Road and the River of Golden Dreams. If you look closely at one of the parking lots in Rainbow Park, you will see a small trail sign for the wonderful trail that takes you through this secluded forest, all the way to Emerald Forest. A River Runs Through It is an insanely winding trail that follows a dizzying route through this captivating forest with Twentyone Mile Creek running through it. A popular, though brutally challenging bike trail, A River Runs Through It has numerous, elaborate ramps, small bridges, and one large bridge that spans Twentyone Mile Creek. A River Runs Through It has a couple shortcut trails that cut a couple kilometres off of it to make it a more manageable and enjoyable hiking trail. If you add in another two connecting trails, you can turn A River Runs Through It into a beautiful 6 kilometre circle route. ARRTI continued here...

Armchair Glacier in Garibaldi Park, Whistler

![]() Armchair Glacier is one of the many easily identifiable mountain features around Whistler. Along with Wedge Mountain and Black Tusk, Armchair Glacier has a distinct shape that it is named after. Armchair Glacier can be seen from a considerable distance and from many places in Whistler. In the winter it is a solid white ridge with three peaks and in the summer the ridge and peaks are bare rock and the glacier can be seen as a solid, horizontal line below. The three-peak mountain ridge above Armchair Glacier is actually called Mount Weart. Despite its distinct armchair appearance and it being known for decades as Armchair Mountain, or simply Armchair, in 1930 the Garibaldi Park Board officially had the name changed to Mount Weart. John Walter Weart(1861-1941) was a lawyer, politician and the chairman of the Garibaldi Park Board at the time of the name change. Though officially called Mount Weart by the Geographical Names Board of Canada, the original name Armchair is still almost universally used. Armchair Glacier continued here...

Armchair Glacier is one of the many easily identifiable mountain features around Whistler. Along with Wedge Mountain and Black Tusk, Armchair Glacier has a distinct shape that it is named after. Armchair Glacier can be seen from a considerable distance and from many places in Whistler. In the winter it is a solid white ridge with three peaks and in the summer the ridge and peaks are bare rock and the glacier can be seen as a solid, horizontal line below. The three-peak mountain ridge above Armchair Glacier is actually called Mount Weart. Despite its distinct armchair appearance and it being known for decades as Armchair Mountain, or simply Armchair, in 1930 the Garibaldi Park Board officially had the name changed to Mount Weart. John Walter Weart(1861-1941) was a lawyer, politician and the chairman of the Garibaldi Park Board at the time of the name change. Though officially called Mount Weart by the Geographical Names Board of Canada, the original name Armchair is still almost universally used. Armchair Glacier continued here...

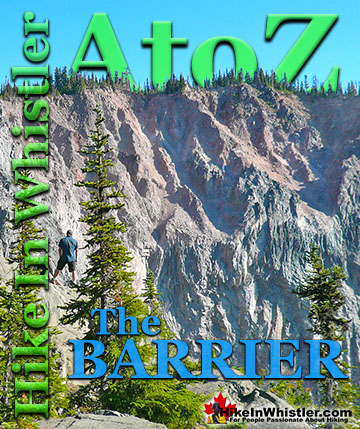

The Barrier in Garibaldi Park

![]() The Barrier formed as a result of huge lava flows from Clinker Peak on the west shoulder of Mount Price during the last ice age. About thirteen thousand years ago, the Cheakamus River valley was filled by an enormous glacier, part of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Lava flowed from Clinker Peak and pressed up against the massive glacier. The lava ponded and formed what geologists call an ice-marginal lava flow. An ice-marginal lava flow is interesting because it causes the lava flow that pools against the glacier to cool relatively quickly forming a solid, rock barrier. Behind this barrier of rock, a lava pool forms. As the glacier retreats as it did after the last ice age, this barrier remains and is characterized as large, steep and unstable. The Barrier was formed in this way from this massive lava flow from Clinker Peak. The lava flow has been studied in detail and four “lobes” have been identified. The First Lobe, closest to Clinker Peak pushes into Garibaldi Lake separating Price Bay from the Garibaldi Lake campground. The Second Lobe covers the area separating Garibaldi Lake from Lesser Garibaldi Lake and is the lobe that created Garibaldi Lake. The Third Lobe formed The Barrier and created Lesser Garibaldi Lake. The Fourth Lobe extends from The Barrier and can be seen today as the very abrupt cliffs along the opposite side of the Rubble Creek valley. The Barrier continued here...

The Barrier formed as a result of huge lava flows from Clinker Peak on the west shoulder of Mount Price during the last ice age. About thirteen thousand years ago, the Cheakamus River valley was filled by an enormous glacier, part of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Lava flowed from Clinker Peak and pressed up against the massive glacier. The lava ponded and formed what geologists call an ice-marginal lava flow. An ice-marginal lava flow is interesting because it causes the lava flow that pools against the glacier to cool relatively quickly forming a solid, rock barrier. Behind this barrier of rock, a lava pool forms. As the glacier retreats as it did after the last ice age, this barrier remains and is characterized as large, steep and unstable. The Barrier was formed in this way from this massive lava flow from Clinker Peak. The lava flow has been studied in detail and four “lobes” have been identified. The First Lobe, closest to Clinker Peak pushes into Garibaldi Lake separating Price Bay from the Garibaldi Lake campground. The Second Lobe covers the area separating Garibaldi Lake from Lesser Garibaldi Lake and is the lobe that created Garibaldi Lake. The Third Lobe formed The Barrier and created Lesser Garibaldi Lake. The Fourth Lobe extends from The Barrier and can be seen today as the very abrupt cliffs along the opposite side of the Rubble Creek valley. The Barrier continued here...

In the spring of 1856 more than 25 million cubic metres of rock from The Barrier crashed down the valley of what is today called Rubble Creek. The incredible torrent of volcanic rock boulders crashed down the valley more than 6 kilometres at a speed of more than 30 metres per second. The vertical distance of the debris flow was over 1000 metres measured from the top of The Barrier to the end of the debris field where Rubble Creek meets Cheakamus River. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: The Barrier Continued...

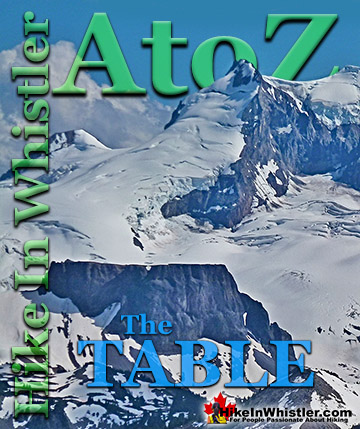

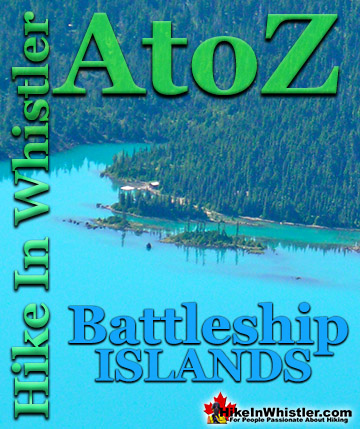

Battleship Islands in Garibaldi Park

![]() The rocky and narrow row of islands in Garibaldi Lake just offshore from the Garibaldi Lake campsite are known as Battleship Islands. Named by the prolific mountaineer Neal Carter in 1927 "..because they are a group of tiny islands with often a single tree as a mast, presenting the appearance of boats, as viewed from Panorama Point(a lookout on Panorama Ridge)." The name "The Battleship Islands" originally appeared on AJ Campbell's 1928 map of Garibaldi Provincial Park. Garibaldi Park maps since 1957 have officially shortened the name to Battleship Islands. Battleship Islands continued here...

The rocky and narrow row of islands in Garibaldi Lake just offshore from the Garibaldi Lake campsite are known as Battleship Islands. Named by the prolific mountaineer Neal Carter in 1927 "..because they are a group of tiny islands with often a single tree as a mast, presenting the appearance of boats, as viewed from Panorama Point(a lookout on Panorama Ridge)." The name "The Battleship Islands" originally appeared on AJ Campbell's 1928 map of Garibaldi Provincial Park. Garibaldi Park maps since 1957 have officially shortened the name to Battleship Islands. Battleship Islands continued here...

Bears in Whistler & Garibaldi Park

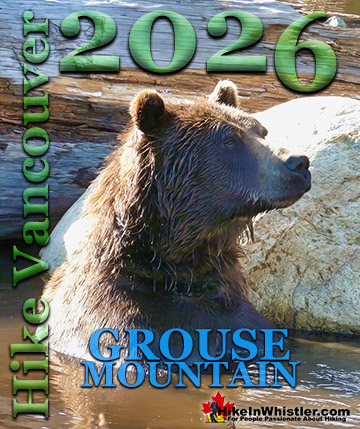

![]() Whistler, the surrounding mountains, and Garibaldi Provincial Park are home to two types of bears. Black bears and grizzly bears. Black bears are frequently seen throughout the valley and often in Whistler Village. Grizzly bears, on the other hand, are rarely seen, and only deep in the wilderness, well away from Whistler Village. Black bears around Whistler are generally skittish and will flee into the forest when approached by people. Unlike grizzly bears, black bears are usually shy and rarely aggressive toward people. If you surprise a bear, make it feel trapped or get too close, you may get swiped with a claw as the bear escapes. To avoid conflicts with black bears, one method is to make yourself known. For example, if hiking in the forest a bear bell is a good way to announce your approach to bears in the area. Bears have tremendously good hearing so your foot steps should alert bears to your presence. If you encounter a black bear in Whistler, you should make yourself heard and seen without being threatening. Talk in a calm voice and back away from the bear slowly. Black bear attacks tend to be entirely the fault of the humans involved. Whether a person doesn’t back away, but tries to get closer, or tries to feed a bear. Or a combination of these. In Whistler, if garbage is not secured and bear proof, it will eventually attract a bear to tear it apart. Then, a person will accidentally or purposely get too close and trigger a panicked attack from the bear. Black bear attacks in Whistler always seem to be of this type, however even these are extremely rare.

Whistler, the surrounding mountains, and Garibaldi Provincial Park are home to two types of bears. Black bears and grizzly bears. Black bears are frequently seen throughout the valley and often in Whistler Village. Grizzly bears, on the other hand, are rarely seen, and only deep in the wilderness, well away from Whistler Village. Black bears around Whistler are generally skittish and will flee into the forest when approached by people. Unlike grizzly bears, black bears are usually shy and rarely aggressive toward people. If you surprise a bear, make it feel trapped or get too close, you may get swiped with a claw as the bear escapes. To avoid conflicts with black bears, one method is to make yourself known. For example, if hiking in the forest a bear bell is a good way to announce your approach to bears in the area. Bears have tremendously good hearing so your foot steps should alert bears to your presence. If you encounter a black bear in Whistler, you should make yourself heard and seen without being threatening. Talk in a calm voice and back away from the bear slowly. Black bear attacks tend to be entirely the fault of the humans involved. Whether a person doesn’t back away, but tries to get closer, or tries to feed a bear. Or a combination of these. In Whistler, if garbage is not secured and bear proof, it will eventually attract a bear to tear it apart. Then, a person will accidentally or purposely get too close and trigger a panicked attack from the bear. Black bear attacks in Whistler always seem to be of this type, however even these are extremely rare.

There has never been an unprovoked bear attack in Whistler and the provoked bear attacks result in minor scratches from a claw swipe. Your best strategy if you find yourself in a close up conflict with a black bear is to back away if you can or fight back. Playing dead will not help you with a black bear, however playing dead has been known to work with grizzly bears. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Glossary: bears continued here...

Bench: Whistler & Garibaldi Park Geology

![]() Bench: a flat section in steep terrain. Characteristically narrow, flat or gently sloping with steep or vertical slopes on either side. A bench can be formed by various geological processes. Natural erosion of a landscape often results in a bench being formed out of a hard strip of rock edged by softer, sedimentary rock. The softer rock erodes over time, leaving a narrow strip of rock resulting in a bench. Coastal benches form out of continuous wave erosion of a coastline. Cutting away at a coastline can result in vertical cliffs dozens or hundreds of metres high with a distinct bench form. Often a bench takes the form of a long, flat top ridge. Panorama Ridge in Garibaldi Provincial Park is an excellent example of a bench. The Musical Bumps trail on Whistler Mountain is another good example of bench formations. Each "bump" along the Musical Bumps trail is effectively a bench. Russet Lake in Garibaldi Provincial Park has a prominent bench adjacent to it. The bench separates Russet Lake and Adit Lakes. Adit Lakes are two idyllic little tarns in a hidden valley separated from the much busier Russet Lake valley by this bench. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: bench continued here...

Bench: a flat section in steep terrain. Characteristically narrow, flat or gently sloping with steep or vertical slopes on either side. A bench can be formed by various geological processes. Natural erosion of a landscape often results in a bench being formed out of a hard strip of rock edged by softer, sedimentary rock. The softer rock erodes over time, leaving a narrow strip of rock resulting in a bench. Coastal benches form out of continuous wave erosion of a coastline. Cutting away at a coastline can result in vertical cliffs dozens or hundreds of metres high with a distinct bench form. Often a bench takes the form of a long, flat top ridge. Panorama Ridge in Garibaldi Provincial Park is an excellent example of a bench. The Musical Bumps trail on Whistler Mountain is another good example of bench formations. Each "bump" along the Musical Bumps trail is effectively a bench. Russet Lake in Garibaldi Provincial Park has a prominent bench adjacent to it. The bench separates Russet Lake and Adit Lakes. Adit Lakes are two idyllic little tarns in a hidden valley separated from the much busier Russet Lake valley by this bench. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: bench continued here...

Bergschrund or Schrund in Garibaldi Park

![]() Bergschrund or abbreviated schrund: a crevasse that forms from the separation of moving glacier ice from the stagnant ice above. Characterized by a deep cut, horizontal, along a steep slope. Often extending extremely deep, over 100 metres down to bedrock. Extremely dangerous as they are filled in winter by avalanches and gradually open in the summer. The Wedgemount Glacier at Wedgemount Lake is a great and relatively safe way to view bergschrund near Whistler. At the far end of Wedgemount Lake the beautiful glacier window can be seen with water flowing down into the lake. From the scree field below the glacier you can see the crumbling bergschrund separate and fall away from the glacier. Up on the glacier you fill find several crevasses. Many are just a few centimetres wide, though several metres deep. Hiking along the left side of the glacier is relatively safe, however the right size of the glacier is extremely dangerous as the bergschrund vary in width and can be measure only in metres instead of centimetres. Hikers venturing up the glacier are advised to keep far to the left or only at the safe, lower edges near the glacier window. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: bergschrund continued here...

Bergschrund or abbreviated schrund: a crevasse that forms from the separation of moving glacier ice from the stagnant ice above. Characterized by a deep cut, horizontal, along a steep slope. Often extending extremely deep, over 100 metres down to bedrock. Extremely dangerous as they are filled in winter by avalanches and gradually open in the summer. The Wedgemount Glacier at Wedgemount Lake is a great and relatively safe way to view bergschrund near Whistler. At the far end of Wedgemount Lake the beautiful glacier window can be seen with water flowing down into the lake. From the scree field below the glacier you can see the crumbling bergschrund separate and fall away from the glacier. Up on the glacier you fill find several crevasses. Many are just a few centimetres wide, though several metres deep. Hiking along the left side of the glacier is relatively safe, however the right size of the glacier is extremely dangerous as the bergschrund vary in width and can be measure only in metres instead of centimetres. Hikers venturing up the glacier are advised to keep far to the left or only at the safe, lower edges near the glacier window. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Geology: bergschrund continued here...

Bivouac or Bivy: Glossary of Whistler

![]() Bivouac or Bivy: a primitive campsite or simple, flat area where camping is possible. Traditionally used to refer to a very primitive campsite comprised of natural materials found on site such as leaves and branches or simply sleeping under the stars. Often used interchangeably with the word camp, however, bivouac implies a shorter, quicker and much more basic and naturally constructed camp setup. For example, at the Taylor Meadows campground in Garibaldi Park, camping is the appropriately used term to describe sleeping there at night as you have constructed tent platforms and are using a tent. If instead you plan to sleep on the summit of Black Tusk, bivouacking would be more accurately used to describe what you are doing as you are not using a tent. In the warm summer months around Whistler you will find people bivouacking under the stars in various places with just a sleeping bag. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Glossary: bivouac continued here...

Bivouac or Bivy: a primitive campsite or simple, flat area where camping is possible. Traditionally used to refer to a very primitive campsite comprised of natural materials found on site such as leaves and branches or simply sleeping under the stars. Often used interchangeably with the word camp, however, bivouac implies a shorter, quicker and much more basic and naturally constructed camp setup. For example, at the Taylor Meadows campground in Garibaldi Park, camping is the appropriately used term to describe sleeping there at night as you have constructed tent platforms and are using a tent. If instead you plan to sleep on the summit of Black Tusk, bivouacking would be more accurately used to describe what you are doing as you are not using a tent. In the warm summer months around Whistler you will find people bivouacking under the stars in various places with just a sleeping bag. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Glossary: bivouac continued here...

Blackcomb Mountain: Glossary of Whistler

![]() Blackcomb Mountain along with Whistler Mountain make up WhistlerBlackcomb Ski Resort, arguably the largest ski resort in North America. Blackcomb Mountain gets it name from its serrated, comb-like edge of black rock along its summit. It is thought to have been named by Don and Phyllis Munday who first climbed it in 1923. In A Passion for the Mountains: The Lives of Don and Phyllis Munday, Kathryn Bridge quotes the explorers, "Then we climbed up and built a small cairn as there was no sign of previous climbers. We suggested the descriptive name of Mt. Blackcomb. The elevation was apparently about 8,000 feet. The time was 2pm." Neal Carter credited the Munday's with naming Blackcomb Peak in 1927 when he submitted the name for the new Garibaldi Park map being created by A.J. Campbell. Carter wrote that it was "Descriptive of the serrated edge of black rock at the summit." It has also been suggested that the name was already in use previous to Don and Phyllis Munday's first ascent in 1923. An unattributed anecdote provided to the Whistler Museum in 2011 credits Alex Philip as coming up with the name. Alex and Myrtle Philip founded Rainbow Lodge in 1914, and it seems unusual that one of the three prominent mountains directly across Alta Lake from the lodge would have remained unnamed for almost a decade. Wedge Mountain and Whistler Mountain are on either side of Blackcomb Mountain and their names had long been in use by the few residents of Alta Lake. A photograph at the Whistler Museum of Jimmy Fitzsimmons that is thought to be taken in 1916 with an interesting caption on the back that reads “..man packing dynamite up to Fitzsimmons Mine(half way up Blackcomb)”. Unfortunately the date and writer of the caption remains unknown and could have been written decades after the picture was taken. So the reference to Blackcomb is still unconfirmed to predate the naming by Don and Phyllis Munday in 1923. Blackcomb Mountain continued here...

Blackcomb Mountain along with Whistler Mountain make up WhistlerBlackcomb Ski Resort, arguably the largest ski resort in North America. Blackcomb Mountain gets it name from its serrated, comb-like edge of black rock along its summit. It is thought to have been named by Don and Phyllis Munday who first climbed it in 1923. In A Passion for the Mountains: The Lives of Don and Phyllis Munday, Kathryn Bridge quotes the explorers, "Then we climbed up and built a small cairn as there was no sign of previous climbers. We suggested the descriptive name of Mt. Blackcomb. The elevation was apparently about 8,000 feet. The time was 2pm." Neal Carter credited the Munday's with naming Blackcomb Peak in 1927 when he submitted the name for the new Garibaldi Park map being created by A.J. Campbell. Carter wrote that it was "Descriptive of the serrated edge of black rock at the summit." It has also been suggested that the name was already in use previous to Don and Phyllis Munday's first ascent in 1923. An unattributed anecdote provided to the Whistler Museum in 2011 credits Alex Philip as coming up with the name. Alex and Myrtle Philip founded Rainbow Lodge in 1914, and it seems unusual that one of the three prominent mountains directly across Alta Lake from the lodge would have remained unnamed for almost a decade. Wedge Mountain and Whistler Mountain are on either side of Blackcomb Mountain and their names had long been in use by the few residents of Alta Lake. A photograph at the Whistler Museum of Jimmy Fitzsimmons that is thought to be taken in 1916 with an interesting caption on the back that reads “..man packing dynamite up to Fitzsimmons Mine(half way up Blackcomb)”. Unfortunately the date and writer of the caption remains unknown and could have been written decades after the picture was taken. So the reference to Blackcomb is still unconfirmed to predate the naming by Don and Phyllis Munday in 1923. Blackcomb Mountain continued here...

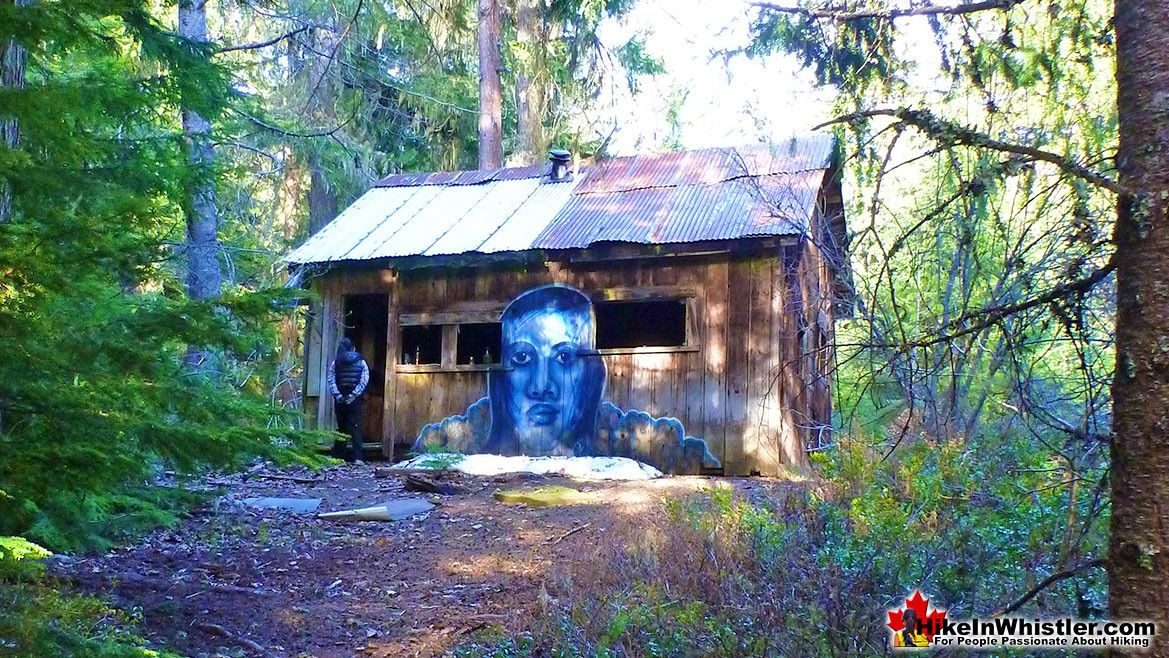

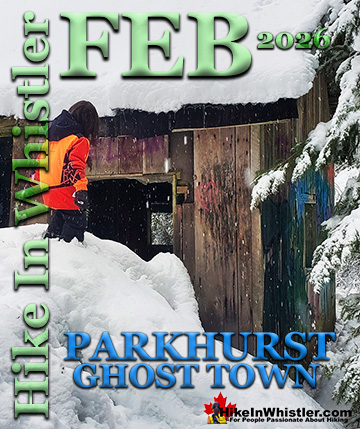

Blue Face House in Parkhurst Ghost Town

![]() Back in 2011 Kups, a Whistler local and now professional muralist painted a hauntingly surreal, blue face on the side of this house. This beautiful mural, along with the fact that this is the last fully intact house in Parkhurst makes it the most well known and photographed structure in the old ghost town. It is difficult to figure out why the Blue Face house outlasted all the others, but it appears to still be quite structurally sound. The old metal roof is very well intact and all the walls are surprisingly solid. The only significant damage seems to be from visitors yanking curtains down or smashing floor boards and wall panels. Any windows that may have existed are long gone and there is no longer a door. A hole in the ceiling has been clawed open to look into the attic which is also somewhat intact with insulation still lining between the two by four ribs. There is even a cute little chimney poking out of the roof, though of course the stove is long gone. There was an old rickety metal bed frame covered with a foam mattress, but now that is mangled across the floor. There was some mention by the Resort Municipality of Whistler when they purchased this land in 2017 to restore this old house. The long term plan is to make Parkhurst into a park somewhat similar to Rainbow Park in that surviving relics would be cleaned up and interpretive murals set up on front of them. One tricky feature of Parkhurst that stands in the way of any development is the train tracks running through. Developing Parkhurst into a park would encourage visitors to an area with multiple railroad crossings and an access bridge that is disintegrating. Blue Face house in Parkhurst continued here...

Back in 2011 Kups, a Whistler local and now professional muralist painted a hauntingly surreal, blue face on the side of this house. This beautiful mural, along with the fact that this is the last fully intact house in Parkhurst makes it the most well known and photographed structure in the old ghost town. It is difficult to figure out why the Blue Face house outlasted all the others, but it appears to still be quite structurally sound. The old metal roof is very well intact and all the walls are surprisingly solid. The only significant damage seems to be from visitors yanking curtains down or smashing floor boards and wall panels. Any windows that may have existed are long gone and there is no longer a door. A hole in the ceiling has been clawed open to look into the attic which is also somewhat intact with insulation still lining between the two by four ribs. There is even a cute little chimney poking out of the roof, though of course the stove is long gone. There was an old rickety metal bed frame covered with a foam mattress, but now that is mangled across the floor. There was some mention by the Resort Municipality of Whistler when they purchased this land in 2017 to restore this old house. The long term plan is to make Parkhurst into a park somewhat similar to Rainbow Park in that surviving relics would be cleaned up and interpretive murals set up on front of them. One tricky feature of Parkhurst that stands in the way of any development is the train tracks running through. Developing Parkhurst into a park would encourage visitors to an area with multiple railroad crossings and an access bridge that is disintegrating. Blue Face house in Parkhurst continued here...

Bungee Bridge on the Sea to Sky Trail

![]() Whistler Bungee Bridge, also known as the Cheakamus Bungee Bridge is a very convenient and beautiful attraction on the way to or from Whistler from Vancouver. Just 20 minutes south of Whistler Village on the Sea to Sky Highway, then just a 3 kilometre logging road takes you right to the stairs up to this amazing bridge. Open year-round and surprisingly accessible, even in the snowy winter months. Thousands of cars drive the Sea to Sky Highway past the turnoff to this wonderful bridge every day and never take a look. With so many sights on the Sea to Sky Highway to see, the Whistler Bungee Bridge is one of the best and certainly one of the most convenient to check out. Part of the fantastic Sea to Sky Trail, the Bungee Bridge in fact it redirected the trail from the now alternate route across the Cal-Cheak suspension bridge. The Sea to Sky Trail is a 180 kilometre walking, hiking, biking, snowshoeing, cross country skiing trail, cuts right through Whistler. This non-motorized, multi-use trail extends from Squamish, through Whistler, north through Pemberton and all the way to D'Arcy. Whistler Bungee Bridge continued here...

Whistler Bungee Bridge, also known as the Cheakamus Bungee Bridge is a very convenient and beautiful attraction on the way to or from Whistler from Vancouver. Just 20 minutes south of Whistler Village on the Sea to Sky Highway, then just a 3 kilometre logging road takes you right to the stairs up to this amazing bridge. Open year-round and surprisingly accessible, even in the snowy winter months. Thousands of cars drive the Sea to Sky Highway past the turnoff to this wonderful bridge every day and never take a look. With so many sights on the Sea to Sky Highway to see, the Whistler Bungee Bridge is one of the best and certainly one of the most convenient to check out. Part of the fantastic Sea to Sky Trail, the Bungee Bridge in fact it redirected the trail from the now alternate route across the Cal-Cheak suspension bridge. The Sea to Sky Trail is a 180 kilometre walking, hiking, biking, snowshoeing, cross country skiing trail, cuts right through Whistler. This non-motorized, multi-use trail extends from Squamish, through Whistler, north through Pemberton and all the way to D'Arcy. Whistler Bungee Bridge continued here...

Bushwhack: Glossary of Whistler

![]() Bushwhack: a term popularly used in Canada and the United States to refer to hiking off-trail where no trail exists. Literally means 'bush' and 'whack'. To make your own trail through the forest by whacking or cutting your way through. Often used to plot a new trail and trail markers are used to mark various routes until a preferred route is found. In Whistler and Garibaldi Provincial Park, bushwhacking may also refer to an early season trail that is littered with fallen trees from winter storms. Existing trails can also become overgrown and require bushwhacking to navigate through. The Brew Lake trail in Whistler requires some bushwhacking for some of the overgrown trail. A bushwhacker is a term used to describe someone who spends a lot of time in the wilderness. Bushwhacking continued here...

Bushwhack: a term popularly used in Canada and the United States to refer to hiking off-trail where no trail exists. Literally means 'bush' and 'whack'. To make your own trail through the forest by whacking or cutting your way through. Often used to plot a new trail and trail markers are used to mark various routes until a preferred route is found. In Whistler and Garibaldi Provincial Park, bushwhacking may also refer to an early season trail that is littered with fallen trees from winter storms. Existing trails can also become overgrown and require bushwhacking to navigate through. The Brew Lake trail in Whistler requires some bushwhacking for some of the overgrown trail. A bushwhacker is a term used to describe someone who spends a lot of time in the wilderness. Bushwhacking continued here...

Buttress: Whistler & Garibaldi Park Geology

![]() Buttress: a prominent protrusion of rock on a mountain, often column-shaped, that juts out from a rock or mountain. They are often so distinct as to be named separately from the mountain they protrude from. Buttresses often make a viable bivouacking option on an otherwise steep mountain. Numerous in the mountains surrounding Whistler, the term buttress is frequently heard while hiking, scrambling, ski touring and climbing.

Buttress: a prominent protrusion of rock on a mountain, often column-shaped, that juts out from a rock or mountain. They are often so distinct as to be named separately from the mountain they protrude from. Buttresses often make a viable bivouacking option on an otherwise steep mountain. Numerous in the mountains surrounding Whistler, the term buttress is frequently heard while hiking, scrambling, ski touring and climbing.

Cairns & Inukshuks/Inuksuks

![]() Cairn: a pile of rocks used to indicate a route or a summit. The word cairn originates from the Scottish Gaelic word carn. A cairn can be either large and elaborate or as simple as a small pile of rocks. To be effective a cairn marking a trail has to just be noticeable and obviously man-made. In the alpine areas around Whistler, above the treeline, cairns are the main method of marking a route. In the spring and fall when snow covers alpine trails, cairns mark many routes. An inukshuk(also spelled inuksuk) is the name for a cairn used by peoples of the Arctic region of North America. Both spelling versions are pronounced nearly as they are spelled. So inukshuk is pronounced inook-shuk, and inuksuk with inook-suk. Though an inukshuk can take many forms similar to a cairn, it is usually represented by large rocks formed into a human shape. The word inukshuk literally translates from two separate Inuit words, inuk "person" and suk "substitute". The 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and Whistler used the inukshuk for the logo of the games. Today you will find several giant rock inukshuks in Vancouver and Whistler at various places. In Whistler there is an impressive inukshuk, several metres high a the peak of Whistler Mountain. Another huge inukshuk sits overlooking Whistler Valley at the Roundhouse next to the Umbrella Bar. The first inukshuk that most visitors to Whistler see is the huge one on Village Gate Boulevard. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Glossary: cairn/inukshuk/inuksuk continued here...

Cairn: a pile of rocks used to indicate a route or a summit. The word cairn originates from the Scottish Gaelic word carn. A cairn can be either large and elaborate or as simple as a small pile of rocks. To be effective a cairn marking a trail has to just be noticeable and obviously man-made. In the alpine areas around Whistler, above the treeline, cairns are the main method of marking a route. In the spring and fall when snow covers alpine trails, cairns mark many routes. An inukshuk(also spelled inuksuk) is the name for a cairn used by peoples of the Arctic region of North America. Both spelling versions are pronounced nearly as they are spelled. So inukshuk is pronounced inook-shuk, and inuksuk with inook-suk. Though an inukshuk can take many forms similar to a cairn, it is usually represented by large rocks formed into a human shape. The word inukshuk literally translates from two separate Inuit words, inuk "person" and suk "substitute". The 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and Whistler used the inukshuk for the logo of the games. Today you will find several giant rock inukshuks in Vancouver and Whistler at various places. In Whistler there is an impressive inukshuk, several metres high a the peak of Whistler Mountain. Another huge inukshuk sits overlooking Whistler Valley at the Roundhouse next to the Umbrella Bar. The first inukshuk that most visitors to Whistler see is the huge one on Village Gate Boulevard. Whistler and Garibaldi Park Glossary: cairn/inukshuk/inuksuk continued here...

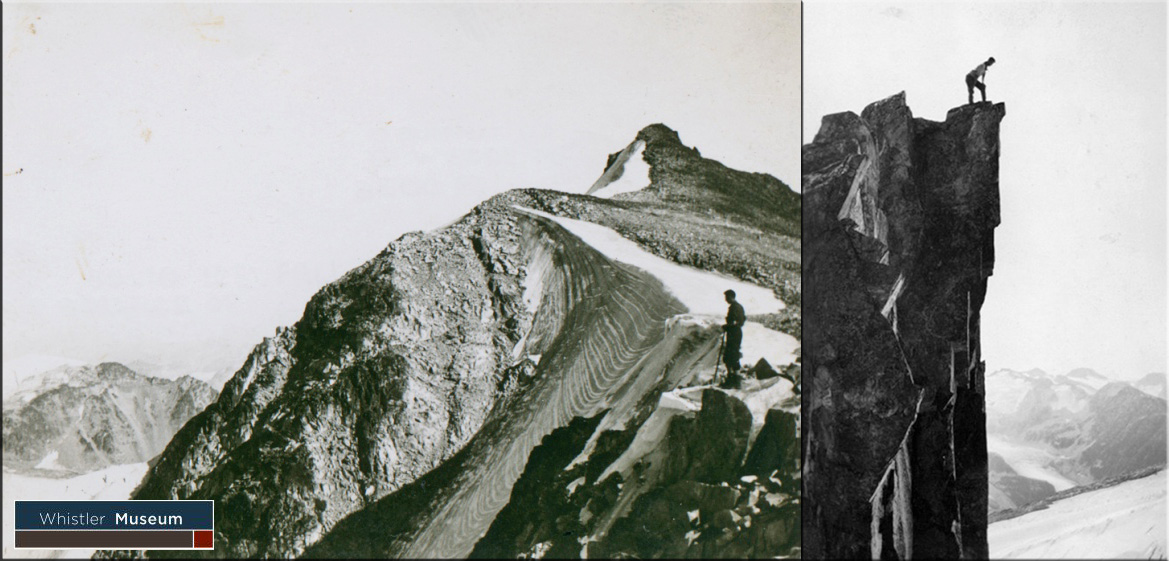

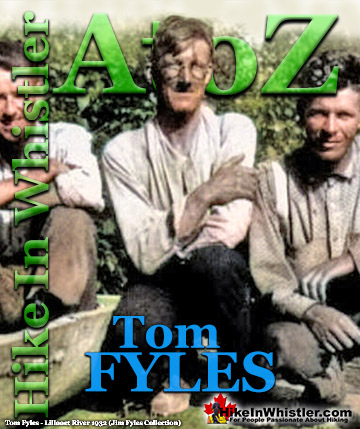

Carter, Neal: Glossary of Whistler

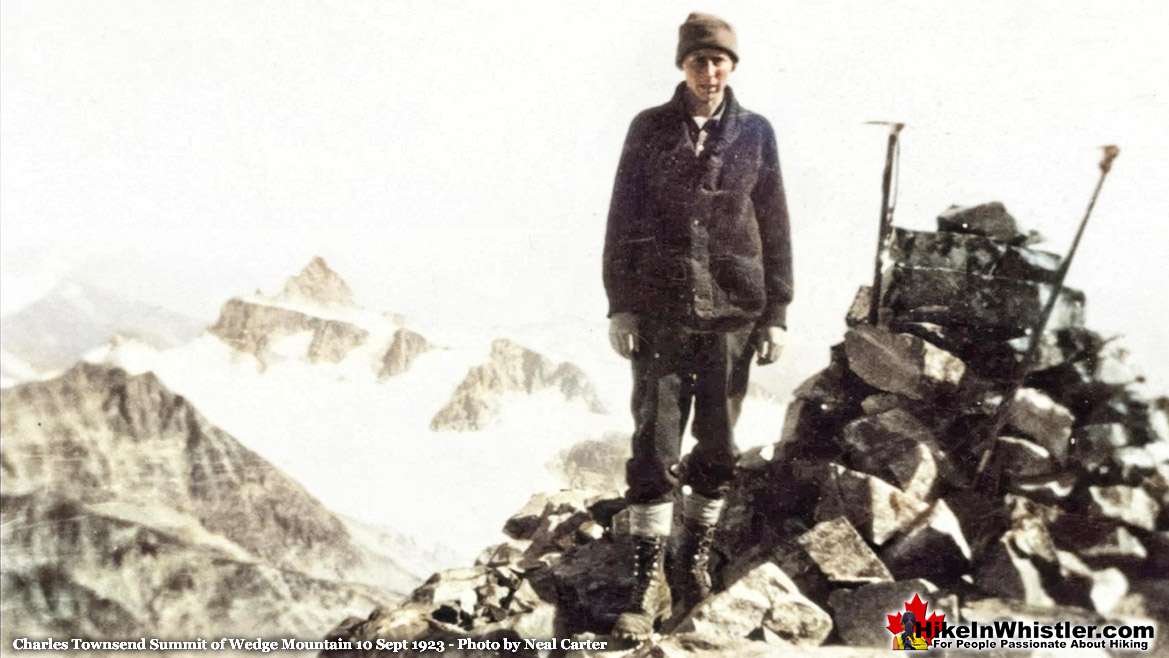

![]() Neal Carter explored and named several mountains around Whistler in 1923 while on a two week expedition with Charles Townsend. They documented and photographed their adventure which included first ascents of Wedge Mountain, Mount James Turner and Diavolo Peak. Their record of this trip is a marvellous look at the local history of Whistler and Garibaldi Park, when what is now Whistler, was a small community called Alta Lake. Neal Marshall Carter was born in Vancouver on December 14th, 1902. Educated at UBC and McGill Universities, he earned a PhD in Organic Chemistry. In his professional life, he was a marine biologist working in fisheries research. He was introduced to mountaineering, and to the British Columbia Mountaineering Club (BCMC) by Tom Fyles, and was a member of that Club from 1920 to 1926, when he left the BCMC for the Alpine Club of Canada. His first love, where climbing was concerned, was the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, though he also climbed extensively elsewhere in Canada and further afield. He liked exploring new peaks, and made several first ascents in what is now Garibaldi Park. He was a skilled surveyor, photographer, and cartographer, and created the first topographical maps of Garibaldi Park, and of the Tantalus Range in the 1920's. In the 1930's he explored peaks at the head of the Lillooet and Toba Rivers, and was a member of a team attempting a first ascent of Mt. Waddington. In the early 1940's he surveyed the Seven Sisters Range near Smithers, and was the first to climb the highest peak, Mt. Weeskinisht. He remained an active climber in the 1950's with two important first ascents: Mt. Monmouth and Mt. Gilbert. Neal Carter was made an honorary member of the Alpine Club in 1974, and for his mapping work, he was named a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. In March, 1978 he died while swimming in Barbados, at the age of 75. Mount Neal in Garibaldi Park is named in his honour. Neal Carter continued here...

Neal Carter explored and named several mountains around Whistler in 1923 while on a two week expedition with Charles Townsend. They documented and photographed their adventure which included first ascents of Wedge Mountain, Mount James Turner and Diavolo Peak. Their record of this trip is a marvellous look at the local history of Whistler and Garibaldi Park, when what is now Whistler, was a small community called Alta Lake. Neal Marshall Carter was born in Vancouver on December 14th, 1902. Educated at UBC and McGill Universities, he earned a PhD in Organic Chemistry. In his professional life, he was a marine biologist working in fisheries research. He was introduced to mountaineering, and to the British Columbia Mountaineering Club (BCMC) by Tom Fyles, and was a member of that Club from 1920 to 1926, when he left the BCMC for the Alpine Club of Canada. His first love, where climbing was concerned, was the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, though he also climbed extensively elsewhere in Canada and further afield. He liked exploring new peaks, and made several first ascents in what is now Garibaldi Park. He was a skilled surveyor, photographer, and cartographer, and created the first topographical maps of Garibaldi Park, and of the Tantalus Range in the 1920's. In the 1930's he explored peaks at the head of the Lillooet and Toba Rivers, and was a member of a team attempting a first ascent of Mt. Waddington. In the early 1940's he surveyed the Seven Sisters Range near Smithers, and was the first to climb the highest peak, Mt. Weeskinisht. He remained an active climber in the 1950's with two important first ascents: Mt. Monmouth and Mt. Gilbert. Neal Carter was made an honorary member of the Alpine Club in 1974, and for his mapping work, he was named a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. In March, 1978 he died while swimming in Barbados, at the age of 75. Mount Neal in Garibaldi Park is named in his honour. Neal Carter continued here...

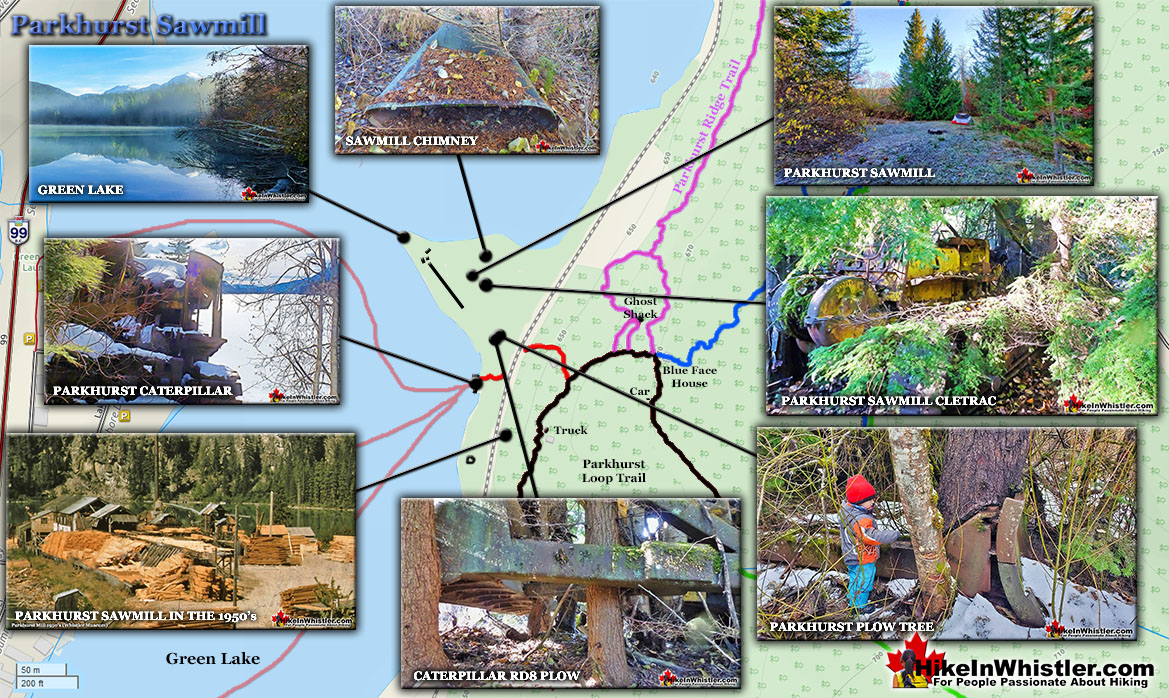

Caterpillar D8 Parkhurst Ghost Town

![]() Along the shore of Green Lake, you will find a monstrous old Caterpillar tractor that dates from the 1930’s. Abandoned here in the 1950’s, it looks as if the driver parked it one day and just never returned to work. In fact that may have been the case as one day in 1956, the sawmill at Parkhurst shut down forever and the town was abandoned. For a logging town in the 1950's having everyone suddenly leave was not unusual and in fact Parkhurst vacated every year when the sawmill shut for the winter. With few job opportunities in the small community most left for the city to find work over the winter months. When Parkhurst was abandoned permanently in 1956, the big Caterpillar tractor was probably simply parked at the edge of Green Lake with the expectation that it would be retrieved later. Maybe it was too expensive or difficult to transport it from the far side of Green Lake. Or maybe it sat unmoved for so long that it became unmovable. Now, decades later it is a bold landmark overlooking Green Lake and a permanent marker, if arriving by boat, to Parkhurst Ghost Town. The Parkhurst Caterpillar D8 continued here...

Along the shore of Green Lake, you will find a monstrous old Caterpillar tractor that dates from the 1930’s. Abandoned here in the 1950’s, it looks as if the driver parked it one day and just never returned to work. In fact that may have been the case as one day in 1956, the sawmill at Parkhurst shut down forever and the town was abandoned. For a logging town in the 1950's having everyone suddenly leave was not unusual and in fact Parkhurst vacated every year when the sawmill shut for the winter. With few job opportunities in the small community most left for the city to find work over the winter months. When Parkhurst was abandoned permanently in 1956, the big Caterpillar tractor was probably simply parked at the edge of Green Lake with the expectation that it would be retrieved later. Maybe it was too expensive or difficult to transport it from the far side of Green Lake. Or maybe it sat unmoved for so long that it became unmovable. Now, decades later it is a bold landmark overlooking Green Lake and a permanent marker, if arriving by boat, to Parkhurst Ghost Town. The Parkhurst Caterpillar D8 continued here...

Caterpillar RD8 in Parkhurst Ghost Town

![]() The second Caterpillar tractor in Parkhurst Ghost Town is considerably harder to find despite being just a few metres from the hulking Caterpillar at the shore of Green Lake. If you bushwhack through the dense forest toward the point of land that the Parkhurst Sawmill was located you will find this second tractor also abandoned in 1956. This tractor is much easier to identify than the other one and appears to be a Caterpillar RD8 built in 1936. Caterpillar made just 9999 1H series RD8 and D8 Caterpillars from 1935 to 1941 and this one was one of the early RD8's at number 334. In 1937, a year after this one came off the assembly line Caterpillar dropped the 'R' from the RD8 name and continued the line as D8. The other Parkhurst Caterpillar, just a few metres away on the shore of Green Lake is a D8 of the same 1H series, and was built in 1939. The Caterpillar RD8 tractor was hugely popular and became renowned worldwide after their widespread use by the Allies during World War II. This Caterpillar at Parkhurst is so hidden by the forest that even standing a couple metres from it you can barely see it. Even in winter when the surrounding trees and bushes have shed their leaves, you still have to get fairly close to spot it. Parkhurst Caterpillar RD8 continued here...

The second Caterpillar tractor in Parkhurst Ghost Town is considerably harder to find despite being just a few metres from the hulking Caterpillar at the shore of Green Lake. If you bushwhack through the dense forest toward the point of land that the Parkhurst Sawmill was located you will find this second tractor also abandoned in 1956. This tractor is much easier to identify than the other one and appears to be a Caterpillar RD8 built in 1936. Caterpillar made just 9999 1H series RD8 and D8 Caterpillars from 1935 to 1941 and this one was one of the early RD8's at number 334. In 1937, a year after this one came off the assembly line Caterpillar dropped the 'R' from the RD8 name and continued the line as D8. The other Parkhurst Caterpillar, just a few metres away on the shore of Green Lake is a D8 of the same 1H series, and was built in 1939. The Caterpillar RD8 tractor was hugely popular and became renowned worldwide after their widespread use by the Allies during World War II. This Caterpillar at Parkhurst is so hidden by the forest that even standing a couple metres from it you can barely see it. Even in winter when the surrounding trees and bushes have shed their leaves, you still have to get fairly close to spot it. Parkhurst Caterpillar RD8 continued here...

Chimney: Whistler & Garibaldi Park Geology

![]() Chimney: a gap between two vertical faces of rock or ice. Often a chimney offers the only viable route to the summit of a mountain. An example of this is Black Tusk in Garibaldi Provincial Park in Whistler. The final ascent of Black Tusk requires climbing a near vertical chimney with crumbling rock all around. Black Tusk is the extraordinarily iconic and appropriately named mountain that can be seen from almost everywhere in Whistler. The massive black spire of crumbling rock juts out of the earth in an incredibly distinct way that appears like an enormous black tusk plunging out of the ground. Whether you spot it in the distance from the top of Whistler Mountain or from dozens of vantage points along the Sea to Sky Highway, its unmistakable appearance is breathtaking. Chimney continued here...

Chimney: a gap between two vertical faces of rock or ice. Often a chimney offers the only viable route to the summit of a mountain. An example of this is Black Tusk in Garibaldi Provincial Park in Whistler. The final ascent of Black Tusk requires climbing a near vertical chimney with crumbling rock all around. Black Tusk is the extraordinarily iconic and appropriately named mountain that can be seen from almost everywhere in Whistler. The massive black spire of crumbling rock juts out of the earth in an incredibly distinct way that appears like an enormous black tusk plunging out of the ground. Whether you spot it in the distance from the top of Whistler Mountain or from dozens of vantage points along the Sea to Sky Highway, its unmistakable appearance is breathtaking. Chimney continued here...

Cirque: Whistler & Garibaldi Park Geology

![]() Cirque: a glacier-carved bowl or amphitheater in the mountains. To form, the glacier must be a combination of size, a certain slope and more unexpectedly, a certain angle away from the sun. In the northern hemisphere, this means the glacier must be on the northeast slope of the mountain, away from the suns rays and the prevailing winds. Thick snow, protected in this way, grows thicker into glacial ice, then a process of freeze-thaw called nivation, chews at the lower rocks, hollowing out a deep basin. Eventually a magnificently circular lake is formed with steep sloping sides all around. Cirque Lake in Whistler is a wonderful example of a cirque formed lake. Cirque Glacier: formed in bowl-shaped depressions on the side of mountains. Cirque continued here...

Cirque: a glacier-carved bowl or amphitheater in the mountains. To form, the glacier must be a combination of size, a certain slope and more unexpectedly, a certain angle away from the sun. In the northern hemisphere, this means the glacier must be on the northeast slope of the mountain, away from the suns rays and the prevailing winds. Thick snow, protected in this way, grows thicker into glacial ice, then a process of freeze-thaw called nivation, chews at the lower rocks, hollowing out a deep basin. Eventually a magnificently circular lake is formed with steep sloping sides all around. Cirque Lake in Whistler is a wonderful example of a cirque formed lake. Cirque Glacier: formed in bowl-shaped depressions on the side of mountains. Cirque continued here...

Class Rating System For Hiking

![]() Class 1,2,3,4,5 Terrain Rating System: a rating system to define hiking, scrambling and climbing terrain levels of difficulty. Separated into 5 levels of difficulty ranging from class 1 to class 5. Class 1 is easy hiking/walking, to class 5 terrain, which is very difficult climbing terrain requiring ropes. Class 5 Terrain: technical climbing terrain and rope required by most climbers for safety. If you are looking at a vertical rock wall, you are effectively looking at class 5 terrain. A typical gym climbing wall is replica of a class 5 terrain rock wall. Class 4 Terrain is one grade easier than class 5 terrain. Class 4 terrain is defined as very steep terrain which rope belays are recommended. Though experienced climbers will find class 4 terrain relatively easy and safe to navigate, novices to climbing will find class 4 terrain difficult, frightening and dangerous. The Lions in North Vancouver requires climbing a short section of class 4 terrain to reach the summit. Class 3 Terrain: is defined by steep terrain requiring the use of hand and foot holds, however, not steep enough to require ropes to navigate safely. The final chimney to Black Tusk(pictured here) would be considered a difficult class 3 section. The final steep section of the Wedgemount Lake trail in Whistler is a characteristic class 3 terrain. Class 2 Terrain: is defined as terrain that may require basic routefinding skills over scree slopes and somewhat steep terrain where you may need your hands for balance or safety. The last couple kilometres to Panorama Ridge in Garibaldi Provincial Park is considered class 2 terrain with the occasional short sections of class 3 terrain. Class 1 Terrain: is defined as a well established trail with little or no steep sections. Class 1 trails are easy to navigate and you would have difficulty getting lost or encountering problems such as dangerous falls or rock slides. A class 1 trail in Whistler would range from the very easy Lost Lake trails in Whistler Village to the more adventurous Cheakamus Lake trail in Garibaldi Provincial Park. Both trails are easy, relaxing, and pose few potential dangers and challenges.

Class 1,2,3,4,5 Terrain Rating System: a rating system to define hiking, scrambling and climbing terrain levels of difficulty. Separated into 5 levels of difficulty ranging from class 1 to class 5. Class 1 is easy hiking/walking, to class 5 terrain, which is very difficult climbing terrain requiring ropes. Class 5 Terrain: technical climbing terrain and rope required by most climbers for safety. If you are looking at a vertical rock wall, you are effectively looking at class 5 terrain. A typical gym climbing wall is replica of a class 5 terrain rock wall. Class 4 Terrain is one grade easier than class 5 terrain. Class 4 terrain is defined as very steep terrain which rope belays are recommended. Though experienced climbers will find class 4 terrain relatively easy and safe to navigate, novices to climbing will find class 4 terrain difficult, frightening and dangerous. The Lions in North Vancouver requires climbing a short section of class 4 terrain to reach the summit. Class 3 Terrain: is defined by steep terrain requiring the use of hand and foot holds, however, not steep enough to require ropes to navigate safely. The final chimney to Black Tusk(pictured here) would be considered a difficult class 3 section. The final steep section of the Wedgemount Lake trail in Whistler is a characteristic class 3 terrain. Class 2 Terrain: is defined as terrain that may require basic routefinding skills over scree slopes and somewhat steep terrain where you may need your hands for balance or safety. The last couple kilometres to Panorama Ridge in Garibaldi Provincial Park is considered class 2 terrain with the occasional short sections of class 3 terrain. Class 1 Terrain: is defined as a well established trail with little or no steep sections. Class 1 trails are easy to navigate and you would have difficulty getting lost or encountering problems such as dangerous falls or rock slides. A class 1 trail in Whistler would range from the very easy Lost Lake trails in Whistler Village to the more adventurous Cheakamus Lake trail in Garibaldi Provincial Park. Both trails are easy, relaxing, and pose few potential dangers and challenges.

Clinker Peak and Clinker Ridge, Mount Price

![]() Clinker Peak is the volcanic vent on Mount Price which lava flows formed The Barrier. Roughly 9000 years ago, Mount Price was an active volcano and Garibaldi Lake did not exist. Where Garibaldi Lake is today was a valley that opened to the much larger Cheakamus Valley. Driving from Squamish to Whistler, you are driving through Cheakamus Valley. The Cheakamus Valley, 9000 years ago lay under the retreating Cordilleran Ice Sheet which at its peak covered 2.5 million square kilometres of western North America. Lava flows from Clinker Peak ponded against this massive ice sheet and formed The Barrier. The Barrier walled in the valley and created Garibaldi Lake. The Barrier is part of the enormous Rubble Creek lava flow which extended northwest . The other main lava flow extended south, then west to form Clinker Ridge.

Clinker Peak is the volcanic vent on Mount Price which lava flows formed The Barrier. Roughly 9000 years ago, Mount Price was an active volcano and Garibaldi Lake did not exist. Where Garibaldi Lake is today was a valley that opened to the much larger Cheakamus Valley. Driving from Squamish to Whistler, you are driving through Cheakamus Valley. The Cheakamus Valley, 9000 years ago lay under the retreating Cordilleran Ice Sheet which at its peak covered 2.5 million square kilometres of western North America. Lava flows from Clinker Peak ponded against this massive ice sheet and formed The Barrier. The Barrier walled in the valley and created Garibaldi Lake. The Barrier is part of the enormous Rubble Creek lava flow which extended northwest . The other main lava flow extended south, then west to form Clinker Ridge.

Mount Price is clearly visible from the Garibaldi Lake campsite, Black Tusk and Panorama Ridge. The picture shown here was taken from Panorama Ridge and shows Mount Price and Clinker Peak quite well. Clinker Ridge extends off behind Clinker Peak and is visible as the ridge in the background on the right. The Barrier is off the the right of the picture, however the lava flow is visible extending up to Clinker Peak.

Cletrac in Parkhurst Ghost Town

![]() Adjacent to the huge Caterpillar tractor in Parkhurst is a large disintegrating wooden dock that is a great place to take in the wonderful view of Green Lake. From the dock if you look to the right you will see a large triangle of deep forest jutting out into the lake. This is where the Parkhurst Sawmill once operated for thirty years. Looking at the almost impenetrable forest now, it is hard to picture this area without trees and with train tracks extending into a large building housing the sawmill with an enormous steel chimney several dozen metres tall. From the dock you can walk back along the short trail that leads to the train tracks. If you turn left, well before the train tracks you can do a little bushwhacking and find your way into the site of the old Parkhurst Sawmill. Not far from the end of the triangle of land and almost in the middle, you will find the huge, old chimney now laying on the ground in several huge pieces. You can even locate the solid steel base of the chimney in the midst of a large bewildering clearing devoid of trees. It takes a little investigating to realize that under about a foot of grass, moss and other forest growth you are standing on massive sheets of thick metal that once was the roof of the Parkhurst Sawmill. For three decades this would have been the loudest and busiest place in the area, now it is a wonderful oasis cut off from the world by the 65-year-old forest that surrounds it. Wandering toward the jungle surrounding the clearing you can’t help noticing some very big trees about 50 metres tall, and appear to be fused together at their base. Called gemels, trees that merge together are not rare, but unusual enough to make you take a closer look. This gemel conceals something extraordinary that may have caused the two trees to become one a long time ago. About a metre directly in front of this tree, a strange old metal pipe emerges from the ground. It is noticeably angled toward the middle of the tree, though deep underground. Circling around the tangle of forest surrounding the tree you find the source of the pipe and can't help but be astonished that you hadn't noticed it before. Another huge, old logging tractor! It appears as though it crashed into this huge gemel and was abandoned. Of course, the opposite is the case. The Parkhurst Cletrac continued here...

Adjacent to the huge Caterpillar tractor in Parkhurst is a large disintegrating wooden dock that is a great place to take in the wonderful view of Green Lake. From the dock if you look to the right you will see a large triangle of deep forest jutting out into the lake. This is where the Parkhurst Sawmill once operated for thirty years. Looking at the almost impenetrable forest now, it is hard to picture this area without trees and with train tracks extending into a large building housing the sawmill with an enormous steel chimney several dozen metres tall. From the dock you can walk back along the short trail that leads to the train tracks. If you turn left, well before the train tracks you can do a little bushwhacking and find your way into the site of the old Parkhurst Sawmill. Not far from the end of the triangle of land and almost in the middle, you will find the huge, old chimney now laying on the ground in several huge pieces. You can even locate the solid steel base of the chimney in the midst of a large bewildering clearing devoid of trees. It takes a little investigating to realize that under about a foot of grass, moss and other forest growth you are standing on massive sheets of thick metal that once was the roof of the Parkhurst Sawmill. For three decades this would have been the loudest and busiest place in the area, now it is a wonderful oasis cut off from the world by the 65-year-old forest that surrounds it. Wandering toward the jungle surrounding the clearing you can’t help noticing some very big trees about 50 metres tall, and appear to be fused together at their base. Called gemels, trees that merge together are not rare, but unusual enough to make you take a closer look. This gemel conceals something extraordinary that may have caused the two trees to become one a long time ago. About a metre directly in front of this tree, a strange old metal pipe emerges from the ground. It is noticeably angled toward the middle of the tree, though deep underground. Circling around the tangle of forest surrounding the tree you find the source of the pipe and can't help but be astonished that you hadn't noticed it before. Another huge, old logging tractor! It appears as though it crashed into this huge gemel and was abandoned. Of course, the opposite is the case. The Parkhurst Cletrac continued here...

Cloudraker Skybridge & Raven's Eye

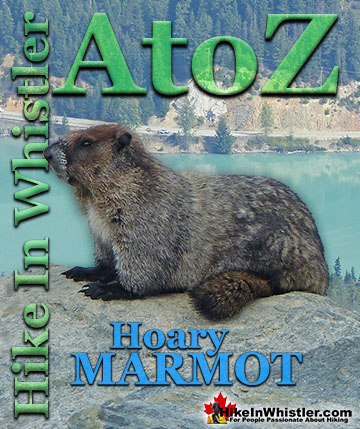

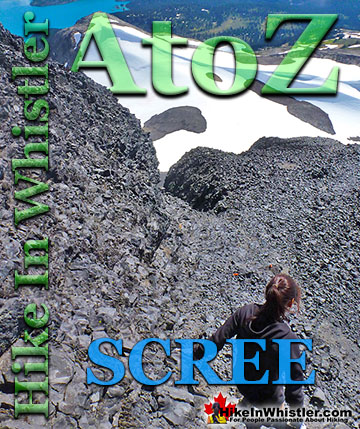

![]() The Cloudraker Skybridge and the Raven’s Eye Cliff Walk are new additions to the summit of Whistler Mountain. The Cloudraker Skybridge stretches 130 metres from just steps from the top of the Peak Express Chair across to the West Ridge. The Raven’s Eye Cliff Walk is a viewing platform that extends over 12 metres up and out from the West Ridge. Both of these exhilarating viewing areas tower way above Whistler Bowl. The Raven's Eye Cliff Walk gives you wonderful views over the Whistler valley as well as an excellent vantage point of the Peak Express Chair with Blackcomb Mountain and the Spearhead Range in the background. The Spearhead Range encompasses Blackcomb Mountain and the Fitzsimmons Range includes Whistler Mountain and extends to Overlord Mountain. Overlord Mountain is where the two mountain ranges meet, separated by Fitzsimmons Creek that runs through Whistler Village into Green Lake. At Whistler’s peak you can hike the cliffs adjacent to the top of the Peak Express Chair on the Whistler Summit Interpretive Walk. This rugged, though very easy 1.6 kilometre set of trails can be done as a figure 8 loop trail.