![]() Neal Carter (14 Dec 1902 – 15 Mar 1978) was a mountaineer and early explorer of the Coast Mountains primarily in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Astoundingly skilled as a mountaineer, Carter also excelled at cartography and surveying which he used to map the vast unnamed and unexplored mountains of BC. He named a staggering number of mountains and alpine features, as well as making at least 25 first ascents, many around what we now call the Whistler Valley.

Neal Carter (14 Dec 1902 – 15 Mar 1978) was a mountaineer and early explorer of the Coast Mountains primarily in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Astoundingly skilled as a mountaineer, Carter also excelled at cartography and surveying which he used to map the vast unnamed and unexplored mountains of BC. He named a staggering number of mountains and alpine features, as well as making at least 25 first ascents, many around what we now call the Whistler Valley.

Neal Carter Mountaineer

- Neal Carter Mountaineering Highlights

- First Ascents by Neal Carter

- 1920: Black Tusk North Pinnacle

- 1922: Second Ascent of The Table

- 1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

- 1924: Climbing in the Tantalus Range

- 1925: Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus

- 1932: Mount Meager Expedition

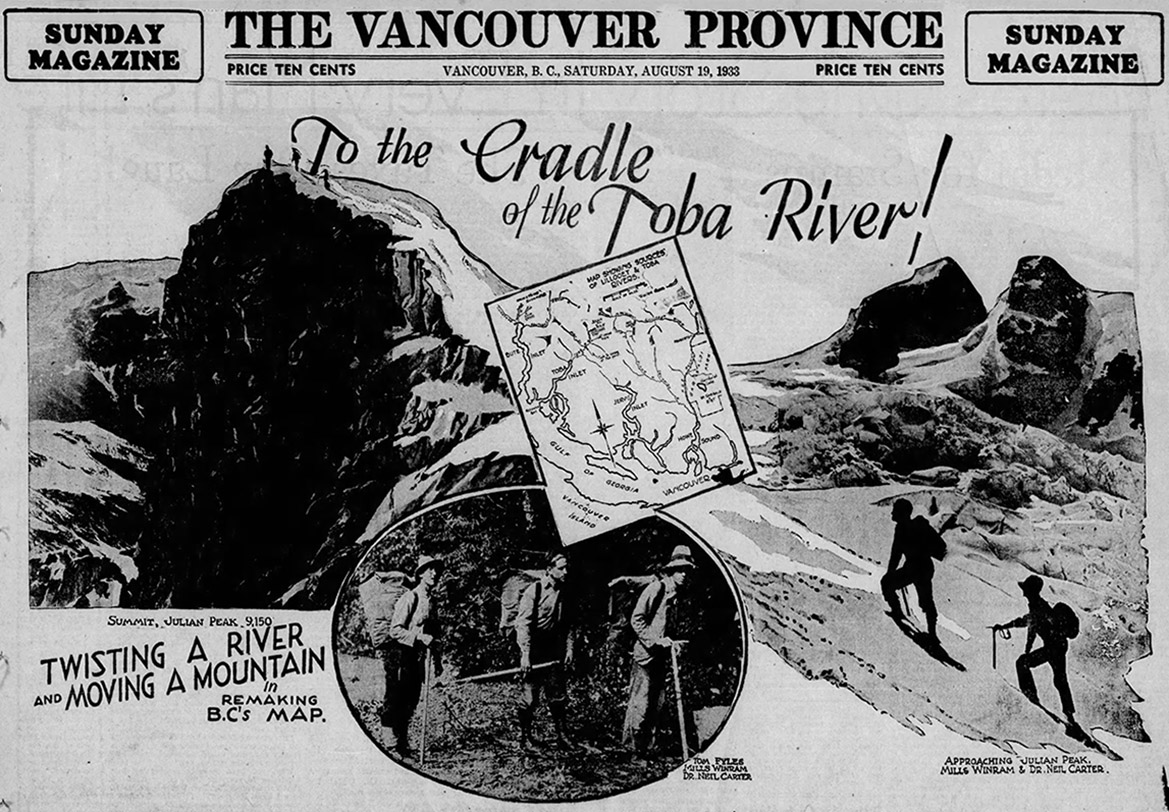

- 1933: To the Cradle of Toba River!

- 1934: Mount Waddington Tragedy

Carter recalled what he thought of the valley when he saw it for the first time in 1923.

“..the skylines seen from their main valley in which Alpha, Nita, Alta, and Green Lakes lie. Alpine features beyond those skylines were pretty sketchy on maps, and few had names.”

A few weeks later he and Charles Townsend would spend two weeks exploring these mountains, nearly all unclimbed, unnamed and very challenging. A skilled mountaineer, surveyor and cartographer, he compiled much of the data that went into the first official topographic map of Garibaldi Park in 1928. Karl Ricker, legendary Whistler mountaineer responsible for the now celebrated Spearhead Traverse, later described Carter's extraordinary work that went into the original Garibaldi Park map.

"...in 1926 the production of the first topographical map of the Garibaldi Lake area. Its construction was a marvel of ingenuity. Painstakingly, he measured two short baselines at either end of the lake; from the ends of both, as well as from several summits, he took great pains to level a simple camera for the necessary panoramic photos. Elaborate calculation from the angles measured on these photos provided the data needed to construct a topo map with 250 foot contour intervals at a scale of on half mile to the inch. Almost all of the calculated peak elevations proved to be within 50 feet or less of the more recently established heights, and the map compares quite favourably, contour-wise, with the 1928 and all subsequent government maps of the area."

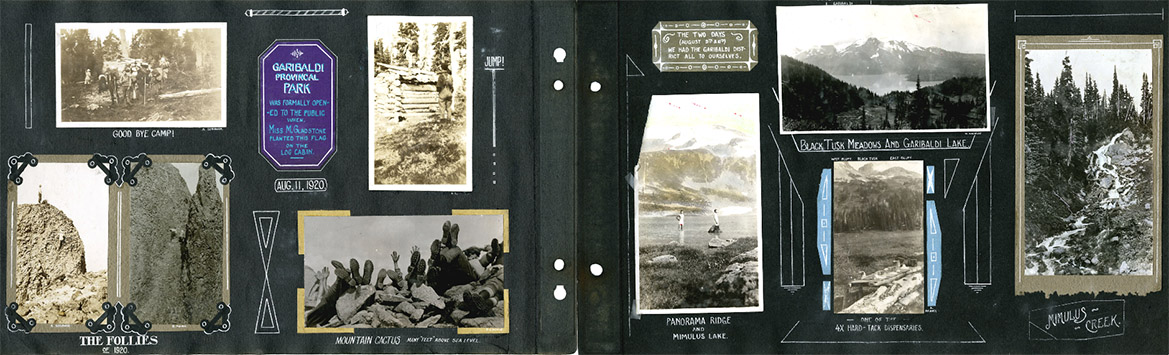

Neal Carter was the driving force in massively increasing the size of Garibaldi Park to include the Spearhead Range and the mountains beyond Wedge Mountain. He photographed his hiking expeditions and compiled several hiking albums, three of which have only recently found their way to the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. The Whistler Museum also has a considerable collection of photos Carter gave to Myrtle Philip at Rainbow Lodge, where he stayed during his amazing two weeks of exploring in 1923. Carter also wrote several wonderful newspaper articles about his fascinating expeditions into the vast and largely unknown Coast Mountains.

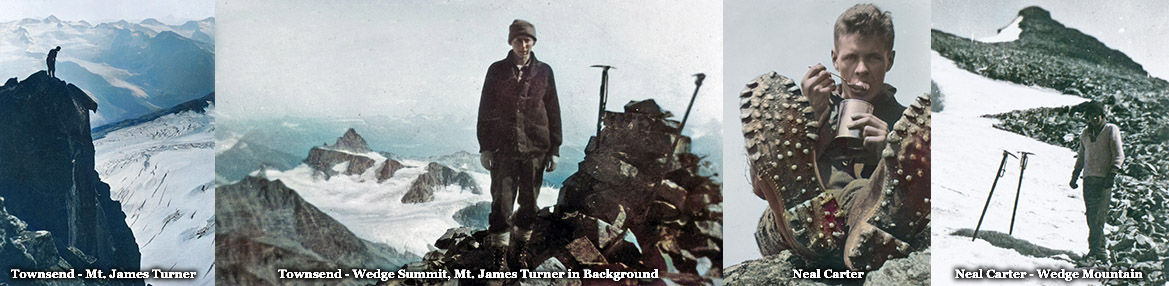

Wedge & Whistler Expedition in 1923

These are some of the photos Neal Carter gave to Myrtle Philip, which now are at the Whistler Museum. The picture on the far left is of Charles Townsend standing on a cliff near the summit of Mount James Turner on September 12th 1923. The second picture shows Townsend standing next to the cairn they built on the summit of Wedge Mountain, two days previously, with Mount James Turner visible in the distance. The third picture is of Neal Carter eating out of a can during the expedition, possibly on Whistler Mountain, though the exact date and location is not known. On the far right is Neal Carter on the summit ridge of Wedge Mountain on September 10th, 1923.

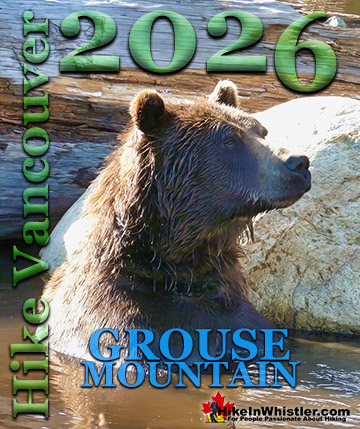

Neal Carter's Introduction to Mountaineering

Carter began climbing the mountains around Vancouver as a teenager and at the age of seventeen he met someone who would change his life forever. In 1920, while hiking with high school friends between Grouse Mountain and Crown Mountain, Carter had a chance encounter with Tom Fyles, arguably the greatest mountaineer of the era. Fyles, a member of the BC Mountaineering Club in Vancouver, introduced him to the club which he immediately joined. Right from the start he was climbing regularly with Fyles and other elite BC mountaineers. 1920 was also the year Carter began studying Chemical Engineering at the University of British Columbia. He would go on to graduate with a B.A.Sc in Chemical Engineering in 1925 and M.A. in 1926. From 1926 to 1929 he studied at McGill University in Montreal where he earned a PhD in Organic Chemistry. The following year he attended the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Dresden, Germany doing post doctoral research. He returned to Canada in 1930 and began his career as a marine biologist in fisheries research.

Neal Carter in 1920 & 1921

These photos are from one of Neal Carter's beautiful photo albums that now reside at the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. The picture on the left with Tom Fyles waving and Neal Carter standing was taken on July 4th, 1920 on The Camel's Head. The middle picture is of Neal Carter on the summit of Mount Baker in September of 1920.

The picture on the right is Carter and a friend with a caption in his album which reads, "OUR WEAPONS FOR THE CONQUEST." The photo is on a page of photos of Carter's Mt. Garibaldi trip he did in the spring of 1921 with Tom Fyles, Celmer Ross and H. J. Graves. This very ambitious and challenging trek covered a considerable distance over mostly snow covered terrain and was the first known springtime ascent of Mount Garibaldi.

Novice to Expert Mountaineer in 1920

Neal Carter's mountaineering activity began at a frenzied pace in 1920 after he joined the BC Mountaineering Club. Several Vancouver area mountains were climbed early in the year such as Cathedral, Goat, Seymour, Grouse, The Lions, Crown Mountain, The Camel's Head, and many more. In the summer the BCMC had their summer camp in Black Tusk meadows and was Carter's first introduction to the newly established Garibaldi Park. Tom Fyles led a large group up Black Tusk, most in the group, including Carter, for the first time. From the broad sloping top of Black Tusk, Fyles decided to make an attempt on the North Pinnacle of Black Tusk. Carter and another young climber, Bill Wheatley joined him and the trio recorded the first known ascent of the true summit of Black Tusk.

Neal Carter's Mountaineering Album at the MONOVA Museum

The following year, in 1921 Carter would join Tom Fyles and Don Munday on a first ascent of the north ridge of Grizzly Mountain. In 1922 another four first ascents were made and two of them, The Bookworms and Deception Peak would also be named by Carter. In 1923 Carter and Charles Townsend went on their incredible two-week expedition into the mountains around the future site of Whistler. Several first ascents were made and unnamed mountains and peaks were named. In 1924 Carter would lead his second springtime expedition into the little explored Tantalus Range. From various summits Carter named several of the unnamed mountains in the range which later became official. In the summer of 1924 he led the BCMC summer camp in the Fitzsimmons Valley and the group made the first ascent of another unnamed mountain, which Carter named Mount Fitzsimmons. In 1925 Carter went on his third springtime expedition in the Tantalus Range in his second attempt to reach the summit of Mount Tantalus.

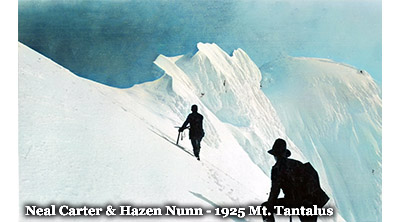

1925 Tantalus Expedition

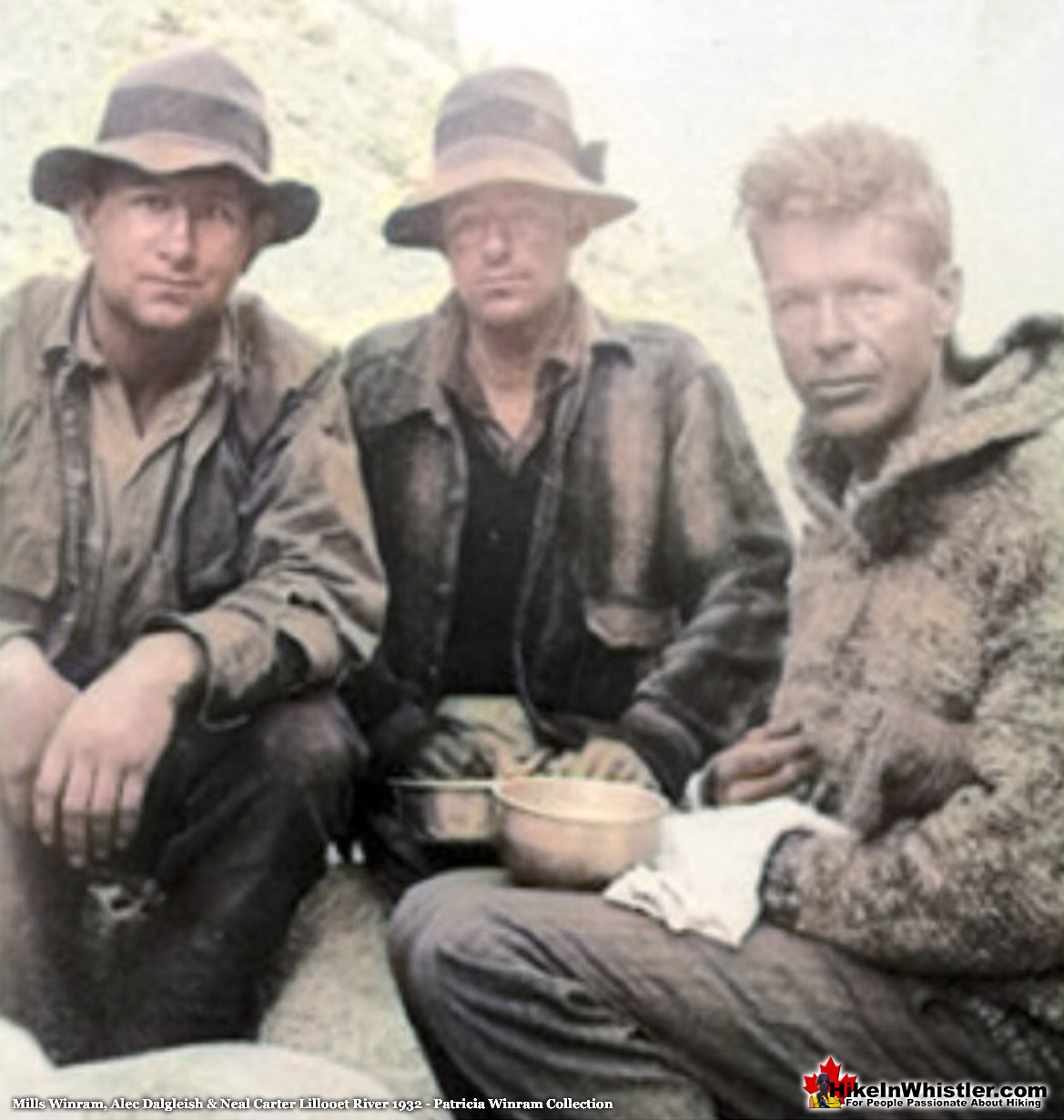

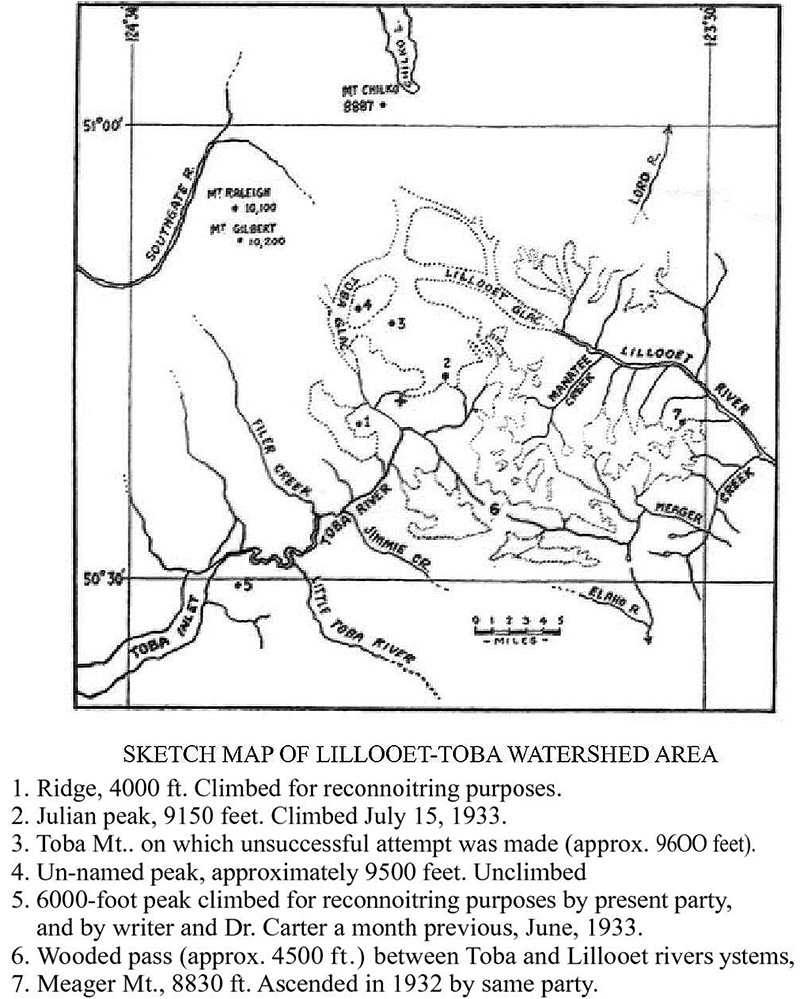

In 1926, 1929 and 1932 Neal Carter made three more first ascents, Luxor Mountain, Mount Davidson and Grimface Mountain. In 1932 and 1933 Carter, Tom Fyles, Mills Winram and Alec Dalgleish went on two amazing expeditions, the first to Mount Meager and the second to the headwaters of Toba River. Several first ascents were made on the Meager expedition and many unnamed peaks were named. The Toba expedition was much more remote and difficult and only one first ascent was accomplished. In 1934, Carter and Dalgleish embarked on another, far more difficult and remote expedition with two other expert mountaineers to attempt a first ascent on Mount Waddington. The attempt would end in tragedy however, when Dalgleish fell to his death on a roped decent.

In the early 1940's Carter surveyed the Seven Sisters Range near Smithers, and was the first to climb the highest peak, Mt. Weeskinisht. He remained an active climber in the 1950's with two important first ascents, Mount Monmouth in 1951 and Mount Gilbert in 1954. While his contributions to climbing and surveying are not widely known, he is certainly one of the greatest British Columbia mountaineers. Mount Neal, located near Wedge Mountain in Garibaldi Park, which he also played a key part in lobbying to expand its borders to their current size, has been named for him, though he yet to climb it. In 1967 he finally climbed it and retraced much of the terrain he hiked in 1923 with Charles Townsend on their expedition to make the first ascent of Wedge Mountain. Karl Ricker wrote about it in the VOC Journal.

"...in 1967 he finally climbed his namesake - Mt. Neal as a long and overdue second ascent. Some V.O.C.ers had "scooped" him with the first ascent in 1950. He and his wife walked back out to the road after that latest episode by way of Wedge Pass."

Carter was made an honorary member of the Alpine Club of Canada in 1974, and for his mapping work, he was named a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He died in 1978 while diving in Barbados at the age of 75.

Neal Carter Mountaineering Highlights

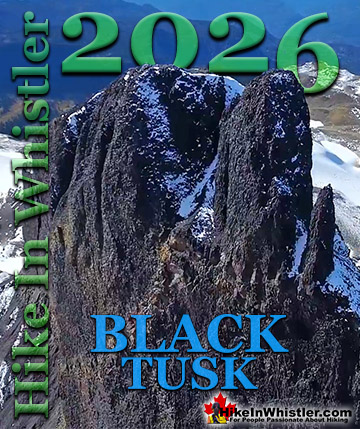

1920: Black Tusk North Pinnacle

1920: Black Tusk North Pinnacle

Neal Carter’s impressive mountaineering feats began at an astounding pace. In 1920, Tom Fyles, Neal Carter and Bill Wheatley made the first known ascent of the north peak of Black Tusk. Slightly higher and just a few metres from main summit, known officially as the true summit. This terrifying feat involved climbing down the crumbling edge of Black Tusk into a gully and up the north pinnacle. Surrounding the pinnacle is a vertical drop of hundreds of metres and most of the surface rock is fractured and finding a solid handhold to climb is difficult. Likely a spur of the moment idea by Tom Fyles, who had the extraordinary ability to climb anything and was absolutely fearless. Continued here...

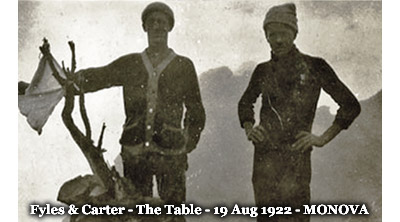

1922: The Table Second Ascent

1922: The Table Second Ascent

In 1922, Neal Carter, Tom Fyles and Bill Wheatley successfully climbed The Table, a mountain so difficult and dangerous that even today, few have climbed it. Theirs was only the second recorded ascent of The Table, with Tom Fyles making the first ascent in 1916. The Table is a crumbling, flat topped mountain that formed as a volcano pushing its way to the surface of a glacier. Located across Garibaldi Lake from Black Tusk, The Table is similarly crumbling and its steep sides make it incredibly hard to climb. In 1922, Fyles reached the top once again and Carter and Wheatley followed with help from Fyles’ rope from the summit. Continued here...

1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

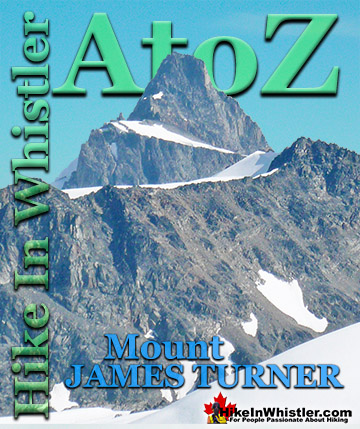

In the summer of 1923 Neal Carter and Charles Townsend went on an incredible two-week climbing expedition around what is now Whistler. They set off from Rainbow Lodge and climbed the previously unclimbed Wedge Mountain. From the summit of Wedge they spotted a mountain to the north in the midst of a maze of glaciers. They named it Mount James Turner and managed its first ascent as well. In the following days they hiked up Singing Pass and to the summit of Overlord Mountain. They made first ascents of two peaks, which they named Diavolo and Whirlwind. Carter left photos at Rainbow Lodge and now they reside in Whistler Museum. Continued here...

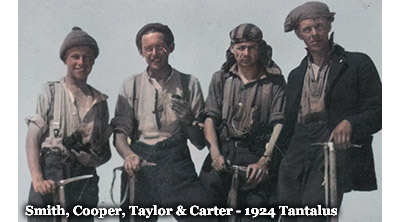

1924: Climbing in the Tantalus Range

1924: Climbing in the Tantalus Range

In the spring of 1924 Neal Carter set out on his second expedition into the Tantalus Range with Hazen Nunn, Ted Taylor, Art Cooper and Fred Smith. Mount Tantalus was their main goal, however, deep springtime snow, bad weather and difficult route finding barred their attempt. Despite not reaching the summit of Tantalus, the expedition reached the summits of several other prominent mountain peaks, such as Alpha, Pelops, Dione and Omega. Along the way they named several unnamed mountains in keeping with the Greek myth of Tantalus. Niobe, Pelops, Dione, Sisyphus and Pandareus are all names created by Neal Carter on this remarkable expedition in 1924. Carter's beautiful photo album of the expedition is now at the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. Continued here...

1925: Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus

Neal Carter’s third expedition into the Tantalus Range was with Charles Townsend and Hazen Nunn. This time the trio of expert mountaineers set out to finally reach the summit of Tantalus. They battled through brutally steep, difficult and dangerous terrain over glaciers and terrifying ridges. With just a couple hundred metres from the summit the knife edge, snow covered ridge gave way to a deep chasm, too dangerous to cross. Despite the unsuccessful attempt, the expedition was later written about by Carter in a thrilling article in the Vancouver Sunday Province, along with some amazing photos taken along the way. Carter also created a wonderful photo album of the expedition which now resides in the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. Continued here...

1932: Meager Expedition

1932: Meager Expedition

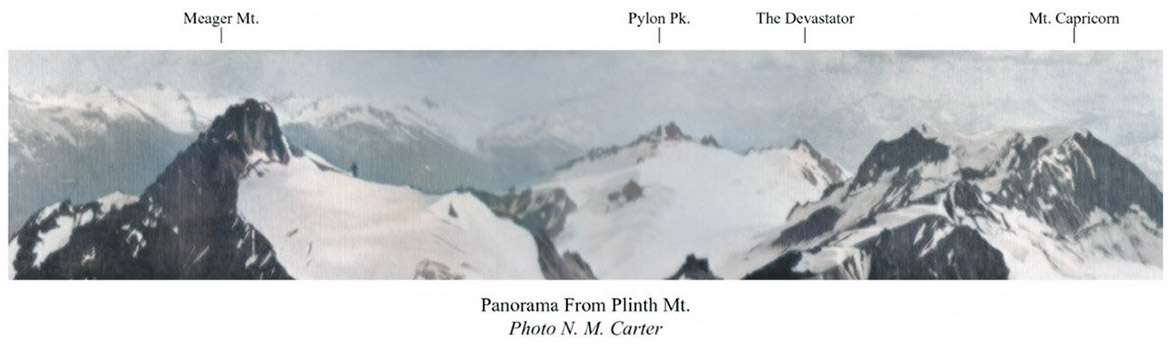

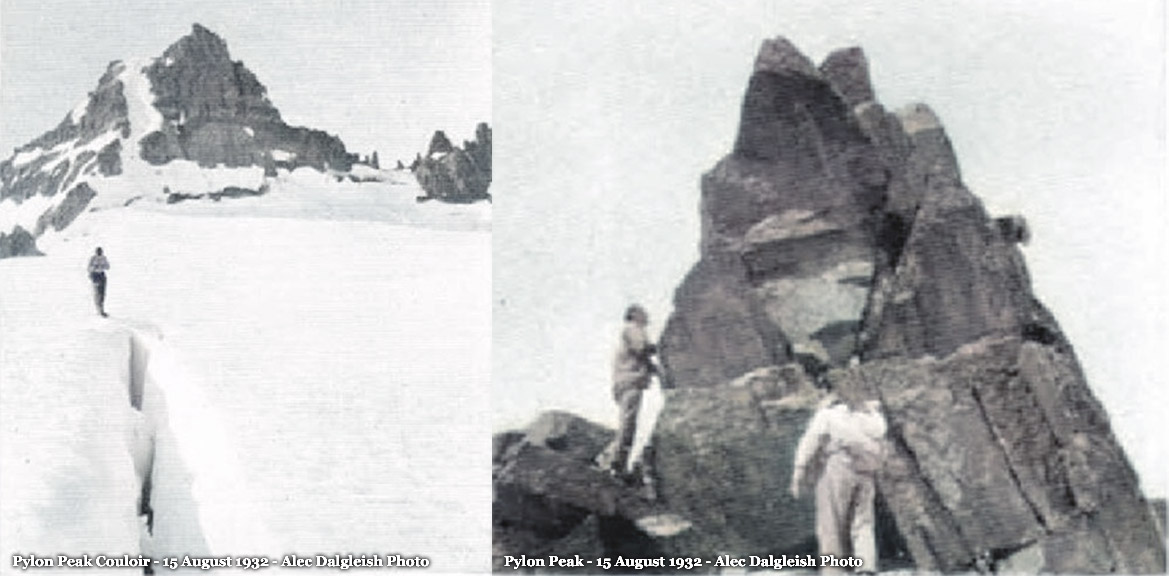

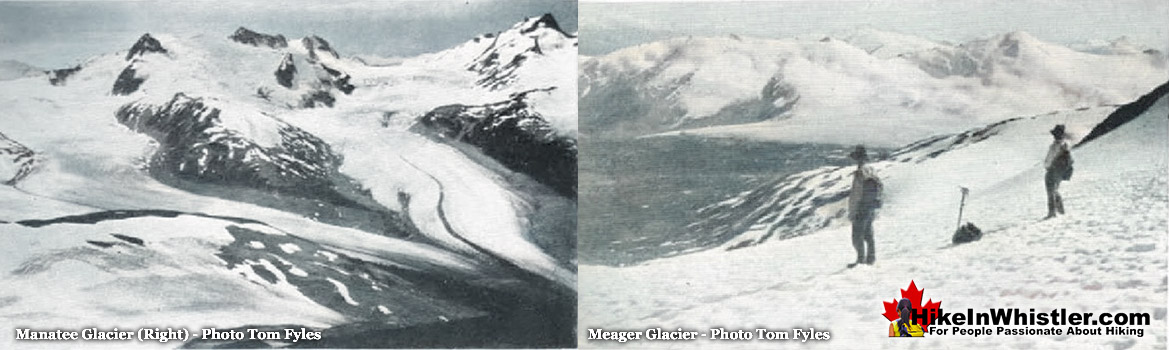

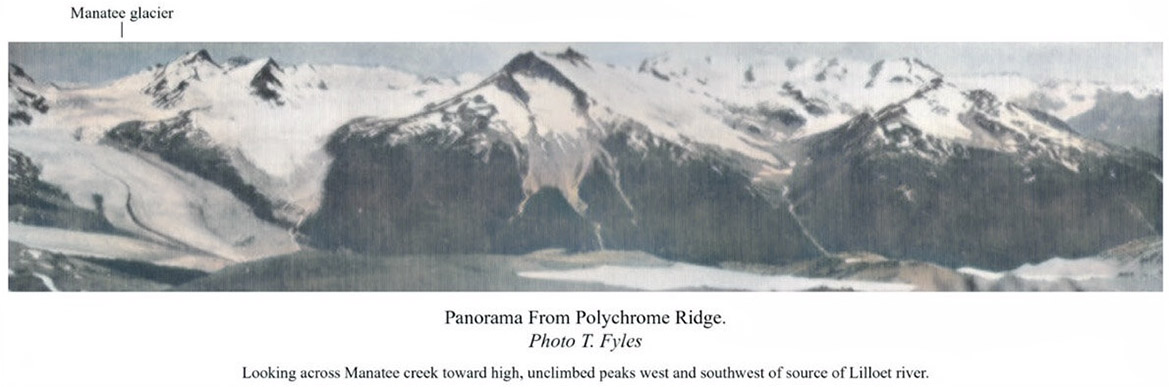

August 8th-20th, 1932 Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Mills Winram and Alec Dalgleish went on a spectacular mountaineering expedition up the headwaters of Lillooet River to Mount Meager. On day 5 Carter recalled, "the toe of a likely looking ridge at an elevation of 1750 feet opposite some hot springs on the bank of the creek was reached." The hot springs they saw are now well known as Meager Hot Springs. In the following days they climbed all six of the volcanic peaks of the Mount Meager massif and named the five unnamed ones. Mount Job, Capricorn Mountain, Devastator Peak, Plinth Peak and Pylon Peak were named. Beyond Meager, unknown peaks stretched to the ocean and another expedition was planned. Continued here...

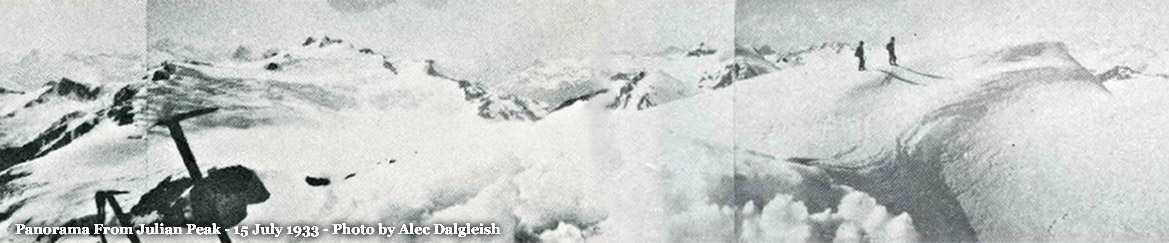

1933: Toba Expedition

1933: Toba Expedition

The unknown mountains they saw from Mount Meager in 1932 were located at the headwaters of Toba River, which drained into Toba Inlet far up the coast of BC. In 1933, Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Mills Winram and Alec Dalgleish teamed up again to explore this vast unknown. The remote Toba Inlet was reached by boat and the expedition involved boating upriver for several miles, then hiking great distances through near impenetrable forest. Despite weathering brutal terrain, considerable bushwhacking, and dangerous river crossings, they managed to make the first ascent of a towering and forbidding mountain they named Mount Julian. Continued here...

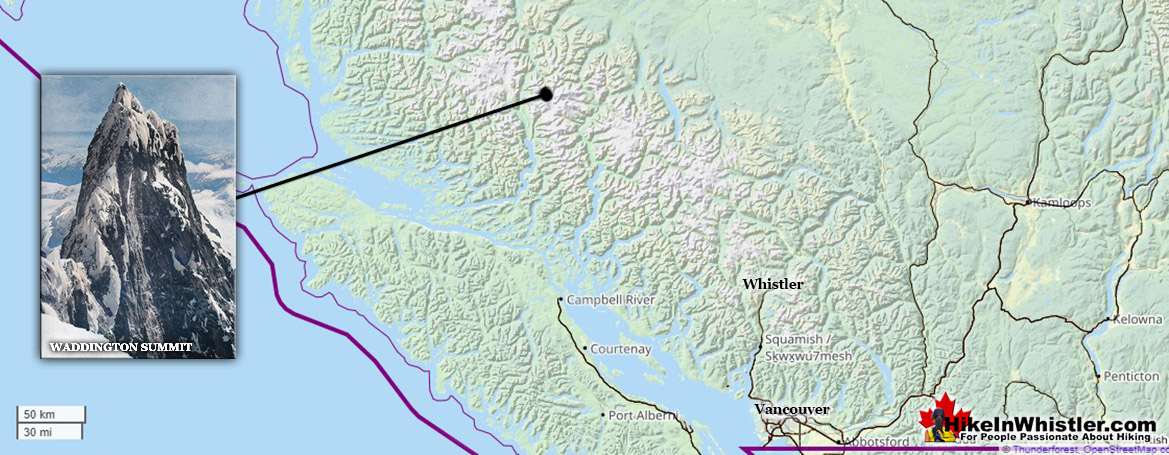

1934: Waddington Tragedy

1934: Waddington Tragedy

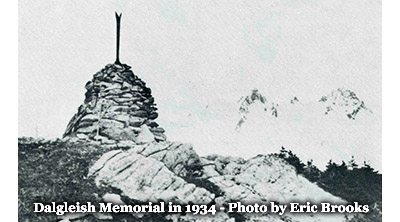

After the Toba Expedition, Alec Dalgleish set his sights on what was the greatest mountaineering prize of the era, the still unclimbed Mount Waddington. The highest peak in the Coast Mountains and requiring a journey of several days to get to. Neal Carter and Eric Brooks joined this brutally challenging expedition to this remote mountain in 1934. The remoteness and difficulty of Waddington was vastly more than the Toba Expedition. The assault on Mount Waddington would end in tragedy however, when Alec Dalgleish fell to his death while on a roped descent along a smooth, outwardly sloping ledge. His belaying rope did not save him as it was cut by the sharp edge of a frost-shattered rock. His body could not be recovered. Continued here...

First Ascents by Neal Carter

- 1920 Black Tusk north peak, true summit first ascent with Tom Fyles and Bill Wheatley.

- 1921 Grizzly Mountain north ridge first ascent with Tom Fyles and Don Munday.

- 1922 Isosceles Peak first ascent with Don & Phyllis Munday, Harold O’Connor and Clausen Thompson.

- 1922 Parapet Peak first ascent with Don & Phyllis Munday, Harold O’Connor and Clausen Thompson.

- 1922 The Bookworms first ascent and named with Charles Townsend.

- 1922 Deception Peak first ascent and named with Charles Townsend.

- 1923 Wedge Mountain first ascent with Charles Townsend.

- 1923 Mount James Turner first ascent and named with Charles Townsend.

- 1923 Whirlwind Peak first ascent and named with Charles Townsend.

- 1923 Diavolo Peak first ascent and named with Charles Townsend.

- 1924 Angelo Peak first ascent with BCMC party previously named by Neal Carter and Charles Townsend.

- 1924 Mount Fitzsimmons first ascent with BCMC party and named by Neal Carter.

- 1926 Luxor Mountain first ascent with Peggy Carter, H. Angus, Neil Hossie, B. Martin and W. Martin.

- 1929 Mount Davidson first ascent with Emmy Milledge.

- 1932 Grimface Mountain first ascent and named with Peggy Carter.

- 1932 Capricorn Mountain first ascent and named with Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram.

- 1932 Mount Meager first ascent with Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram.

- 1932 Plinth Peak first ascent and named with Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram.

- 1932 Pylon Peak first ascent and named with Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram.

- 1932 Devastator Peak first ascent and named with Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram.

- 1932 Mount Job first ascent and named with Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram.

- 1933 Mount Dalgleish first ascent with Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram.

- 1941 Weeskinisht Peak (Seven Sisters Mountain) first ascent with K. Carter, G. Baker and J. Cade.

- 1951 Monmouth Mountain first ascent with A. Melville, I. Kay, T. Marston, D. Blair, W. Sparling and H. Genschorek.

- 1954 Mount Gilbert first ascent with E. Pigou. L. Blumer; A. Melville; P. Sherman; D. Young and J. Young.

1920: Black Tusk North Pinnacle

Tom Fyles, Neal Carter & Bill Wheatley

The August 17th, 1920 edition of the Vancouver Sun newspaper ran a story titled, "Garibaldi Park Is Formally Opened by Local Mountaineers”. The article details several peaks climbed over the two weeks and described their climb of Black Tusk with interesting detail. “Several good climbs were made from the camp last week, one of the most ambitious being the ascent of Black Tusk, a huge basalt rock that projects out of the top of the mountain over 7,000 feet in the air like the horn of a giant rhinoceros.” The article goes on the describe how Black Tusk formed from the plug of an ancient volcano and the only way to climb to the top is done, “by climbing over the projecting rim of a funnel which a lightening bolt has cut in the rock.” This interesting observation is strange and the article doesn’t mention where that theory came from, or how lightening could carve out a huge gouge in a mountain. The article also mentions another strange and improbable incident involving lightening. “One of the treasured trophies in the cairn is an ancient tobacco tin which held the record in the previous cairn. A lightening bolt a few years ago shattered the cairn, blew three feet off the face of Tusk, bored diagonally clean through the tobacco tin, burning the record and dashing the tin a hundred feet away. The present receptacle for the scroll is a common glass “sealer” inside the cairn.” Both of these lightening stories seem hard to believe, and probably made up, but the article does describe another event on Black Tusk that day that is certainly true. The first known ascent of Black Tusk's north pinnacle, the true summit by Tom Fyles, Neal Carter and Bill Wheatley.

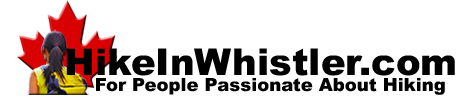

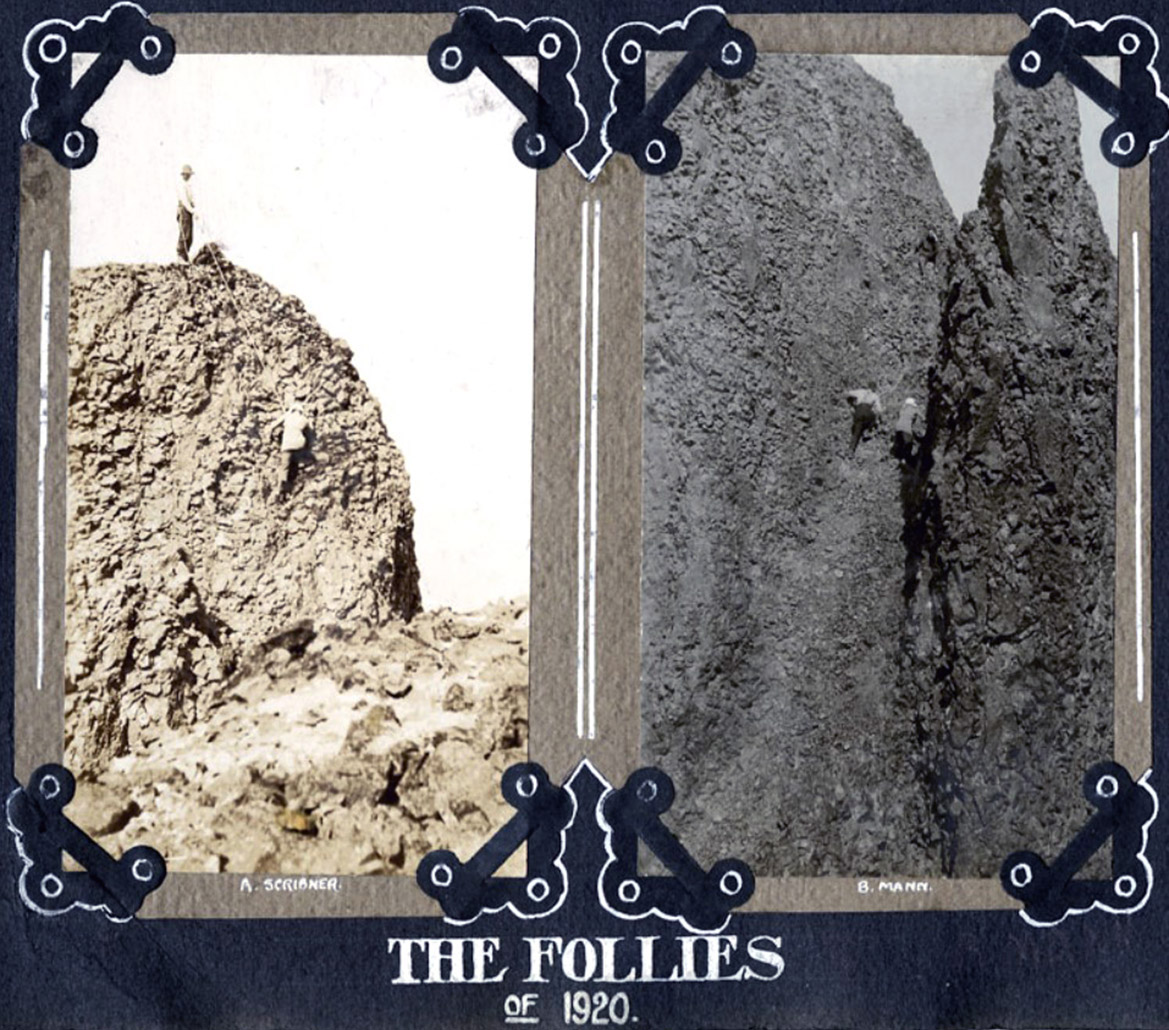

Black Tusk's North Pinnacle Far Away and Up Close

Black Tusk's True Summit

The top of Black Tusk is quite broad, large, flat and slopes down toward the chimney route up. At the opposite end is the high point of Black Tusk and the final destination for everyone that climbs it. Technically this point is not the true summit of Black Tusk. Another, slightly higher pinnacle rises just a few metres from the top edge. This narrow, crumbling pinnacle of rock has a very small area at its peak and getting to it requires climbing down the frightening, vertical edge of Black Tusk and descending into the deep gully between the two peaks and climbing up the near vertical, crumbling side of the narrow pinnacle. Terrifying, dangerous, very difficult, and almost certainly unclimbed, Tom Fyles had to climb it. Fearless and an astoundingly skilled climber, in 1916 Fyles had climbed The Table, a similarly crumbling, yet vastly larger and more challenging mountain. By comparison, this tiny ascent must have looked to Fyles as a short and simple climb, which to an astoundingly skilled climber like him, it was. From the top of the crumbling pinnacle and true summit of Black Tusk, Fyles was soon joined by Neal Carter and Bill Wheatley, with the encouraging help of Fyles’ rope. Years later Carter would recall, “I had shown signs of mountain madness even during my first trip into Garibaldi (1920) when I helped build that little cairn on that rotten bit of the Black Tusk that sticks up (a foot or so higher than the main peak) to the west.” These two photos are from one of Neal Carter's climbing albums on exhibit at MONOVA Museum in Vancouver.

Neal Carter North Pinnacle Ascent - 11 Aug 1920

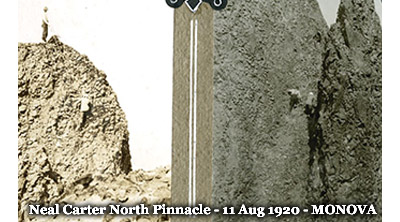

1922: Second Ascent of The Table

Tom Fyles, Neal Carter & Bill Wheatley

In 1922 Neal Carter, Tom Fyles and Bill Wheatley made the second recorded ascent of The Table. It is hard to appreciate the extraordinary difficulty of this accomplishment. Climbing The Table involves several terrifying vertical ascents up walls of crumbling rock which dislodge frequently and rain down on climbers below. Thirty-seven years later, in 1959 Neal Carter wrote a letter to Karl Ricker, in which he briefly mentioned the remarkable day.

“I was on the second ascent (again in 1922 - I must have been crazy that year). That's one mountain that I never want to climb again! The only consolation was that it was in the fog, so we couldn't see how far the drop below us was as we three clung to the loose chunks of rock that kept threatening to pull out of the sheer wall.”

The Table and Mount Garibaldi

Pictured below is the start of the successful 1922 ascent of The Table with Tom Fyles on the left, Bill Wheatley top middle and Neal Carter bottom right with the famous rope around his neck that remained fixed for a decade. The fourth person in the picture on the lower left is Joseph T. Hazard, an expert mountaineer and writer from Seattle. In his 1948 book Pacific Crest Trails, Hazard recalls a hilarious comment made by Tom Fyles poking fun at him, likely at the time this photo was taken. "You are too heavy, Hazard, to make The Table. You can climb anything that will hold you--but The Table will not. It will scale off under you and drop you into oblivion! Don't try it."

Fyles, Hazard, Wheatley & Carter The Table - 19 Aug 1922

"Top of Table Mountain is Reached"

In an article written for The Province newspaper shortly after the 1922 ascent, Neal Carter wrote about the treacherous climb in detail. Recalling how after the first ascent in 1916. “Mr. Fyles, pronounced it so rotten and loose as to warrant the name of an unjustifiable hazard; in 1920 he made two attempts to re-ascend it, but failed. This time we started off with 180 feet of alpine rope and the slogan “Table or bust.” We nearly “bust.”" Neal Carter then continues the story in beautifully vivid detail.

The weather was most unpropitious and soon after commencing the ascent, rain began to fall. Tom Fyles went up first, with a rope about his waist, and all went well up to the first little pinnacle. Here it was deemed advisable to continue up the arête at the low end; said arête being about as solid as a child’s house of blocks. Sixty feet of rope brought the party to the next stopping place, a little dip in the sharp arête that made a niche just big enough for two of us while Tom continued the ascent with 120 feet of rope dragging behind him. Shower after shower of rock whizzed past our heads as we sat almost motionless for fifty-five minutes during which only 110 feet were gained. Finally, a dim shout was heard: “All right,” and our stiffened bodies were given a chance to exercise themselves on a slanting traverse of a precipitous rock-face composed of the shakiest material imaginable. Fully half a ton of rocks were unavoidably dislodged during the ascent and descent; and did not add much to the confidence of the climbers as they went singing past in the fog to fall uninterrupted on the scree slopes below.

As the rope was followed upward in the fog, it finally landed us beside Mr. Fyles in another niche on a level with the summit, but connected to it by about twenty-five feet of wobbly, knife-edged ridge. One of these rocks was partially demolished to enable us to grip a reasonably firm rock as we straddled along it. Once the summit was reached, it was like stepping on to a macadamized field. We built a good-sized cairn on the edge in plain view from below, and placed our own as well as Mr. Fyles’ previous record in a subsidiary cairn beside it, around which were transplanted a few erigeron, or mountain daisies. Several meanings may be taken from this as to our feelings towards the descent; however, camp was reached again at 7 o’clock and The Table was conquered for the second time after a five and a half hour climb of 240 feet and back, though 120 feet of rope remain attached to the top as a mute token of a guaranteed safe descent for all three of us. It may be some time before another name is added to the three already in the cairn.

Tom Fyles & Neal Carter The Table - 19 Aug 1922

1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

Neal Carter & Charles Townsend

In the summer of 1923 Neal Carter was working as a surveyor in the valley stretching from Brandywine Falls to Green Lake. This valley wouldn’t be known as Whistler Valley for several more decades. Carter helped cut the first packhorse trail to Cheakamus Lake and hiked up to Whistler Mountain via Singing Pass in order to sketch the shape of Cheakamus Lake. From high up on Whistler Mountain he got a close look at Wedge Mountain, which Alex Philip would later tell him was thought to be unclimbed. Alex Philip was, along with his wife Myrtle Philip, the owners of Rainbow Lodge at Alta Lake. Alex Philip further mentioned that he believed Wedge Mountain to be a higher mountain than Mount Garibaldi. In 1923 Mount Garibaldi was the highest mountain in Garibaldi Park, which at the time extended only as far north as Cheakamus Lake. At the end of the summer with his survey work finished he persuaded Charles Townsend to join him on a two week expedition to climb Wedge Mountain and the mountains beyond.

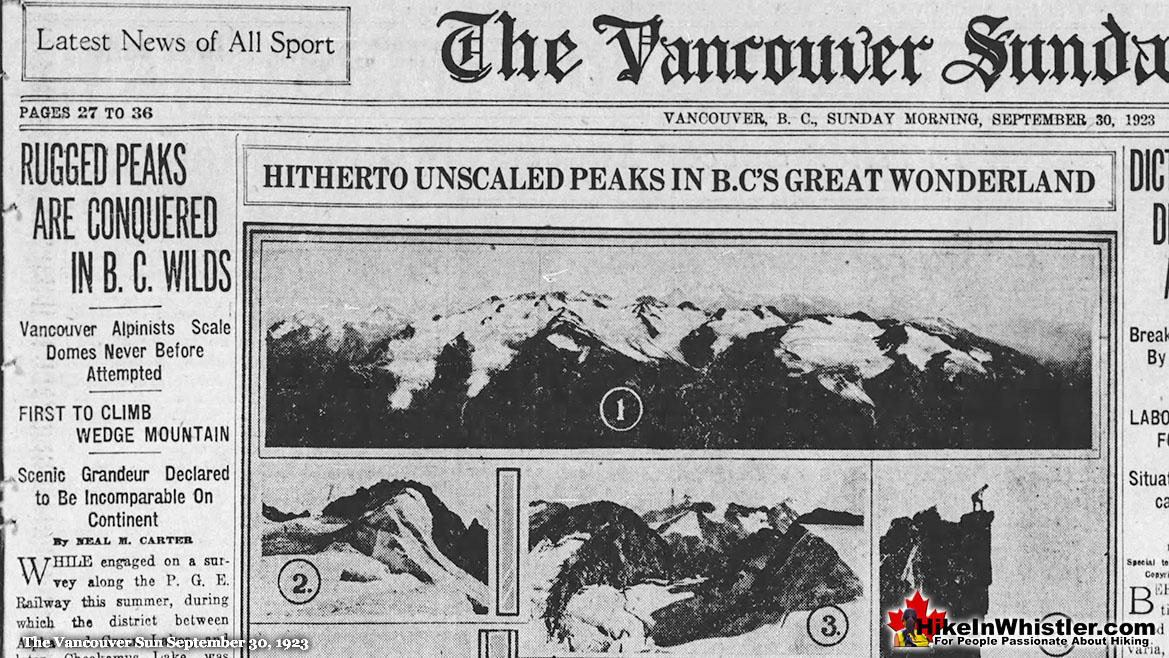

Neal Carter's Article in The Vancouver Sun - 30 Sept 1923

Neal Carter wrote a wonderful article about his two weeks exploring the mostly unclimbed and unnamed mountains around Alta Lake, decades before it became known as Whistler Valley. His article is shown further below in bold. Dates have been added as well as photos he took that were included in this article and several other photos that were not. Some of the original black and white photos have been colourized to enhance their appearance. Wedgemount Creek mentioned several times in the article is now officially named Wedge Creek. Turner Glacier has also been officially renamed as Chaos Glacier.

RUGGED PEAKS ARE CONQUERED IN BC WILDS

By NEAL M. CARTER

While engaged on a survey along the P.G.E. Railway this summer, during which the district between Alpha and Green Lakes, and later, Cheakamus Lake, was traversed, I had occasion to view many fine unclimbed mountain peaks in the unmapped and practically unexplored regions around the heads of the valleys lying to east of the railway, and at the head of Cheakamus Lake. Chief among these was a fine peak well known to visitors at Rainbow Lodge as “Wedge Mountain” from its characteristic shape as viewed from that angle. Looking up Fitzsimmons Creek valley from a few hundred yards beyond the lodge on the railway, another high series of mountains may be seen, the highest of which was climbed this summer by Mr. and Mrs. Don Munday of the BC Mountaineering club while reconnoitring from a proposed site for a summer mountaineering camp. Having to be content while surveying with viewing these peaks from the depths of valleys, I determined to return with a fellow member of the Mountaineering club to investigate them at closer range during a two weeks pleasure trip.

FULLY EQUIPPED

With the main object of making the first climb recorded of Wedge Mountain, Mr. Charles T. Townsend and myself left Vancouver on Saturday morning, September 8, with full equipment to contend with any glacial or rock features we should encounter. This included heavily nailed boots, ice-axes, snow glasses, a rope, etc., as well as an aneroid and mapping facilities to bring back data of our trip. Food, clothing and a tent were chosen such as would keep the backpacking within the limits of a “pleasure” trip. Arriving at Alta Lake, we were in time to have our last civilized meal at Rainbow Lodge before turning in a little way up the track under the stars.

September 9,1923: Alta Lake to Camp #1 on Parkhurst Mountain

Sunday dawned a beautifully clear day, and by 10:30am we had hiked down the track to Mile 42 on Green Lake. Opposite here, a ridge comes down from the shoulder of Wedge around the base of which Wedgemount Creek wends its way through box canyons to join the Green River farther down the railway. So, turning our faces to the east, we struck into the timber and after a brief lunch of hard tack, chocolate and cheese, crossed Wedgemount Creek on a slippery log and commenced the real climbing.

Neal Carter Crossing Wedge Creek - 9 Sept 1923

OBSTACLES ENCOUNTERED

All through the hot afternoon, a tiresome series of hollows, ridges and rocky bluffs was encountered; sometimes treading on a mossy carpet, no pushing our way through dense tangles of blueberry bushes, then perhaps scrambling up some stony cliff. Without so much as a glimpse of our mountain all the way, and only one drink of water, we were heartily glad to come out at timberline about 6 o’clock and find ourselves withing an easy day’s journey of the peak. Another hour was spent in searching for water, which was eventually founded trickling from under a small ice sheet. Here we pitched our tent.

Neal Carter at Camp #1 Wedge Mountain in Background

September 10, 1923: Wedge Mountain

The weather on the 10th was fine, the aneroid stationary at 5800 feet, so we left camp in the morning for the final climb on Wedge Mountain in fine spirits.

Wedge Mountain from Ridge Above Camp - 10 Sept 1923

Continuing up the ridge leading towards the mountain, an unavoidable gap forced us to cross mountainous remains of some huge glacier of the past, and it was after 11am before we reached the base of the final 2000-foot slope of broken, jagged chunks of rock that form the face of which looks so perpendicular from Alta Lake. This really was at an angle of about 40 degrees though steeper in places where the bedrock was exposed almost perpendicularly.

West Face of Wedge Mountain - 10 Sept 1923

No especial care or skill was needed in the final ascent except to prevent the foot being caught when three or four 500-pound rocks would shift and settle when stepped on.

Charles Townsend Climbing Wedge Mountain - 10 Sept 1923

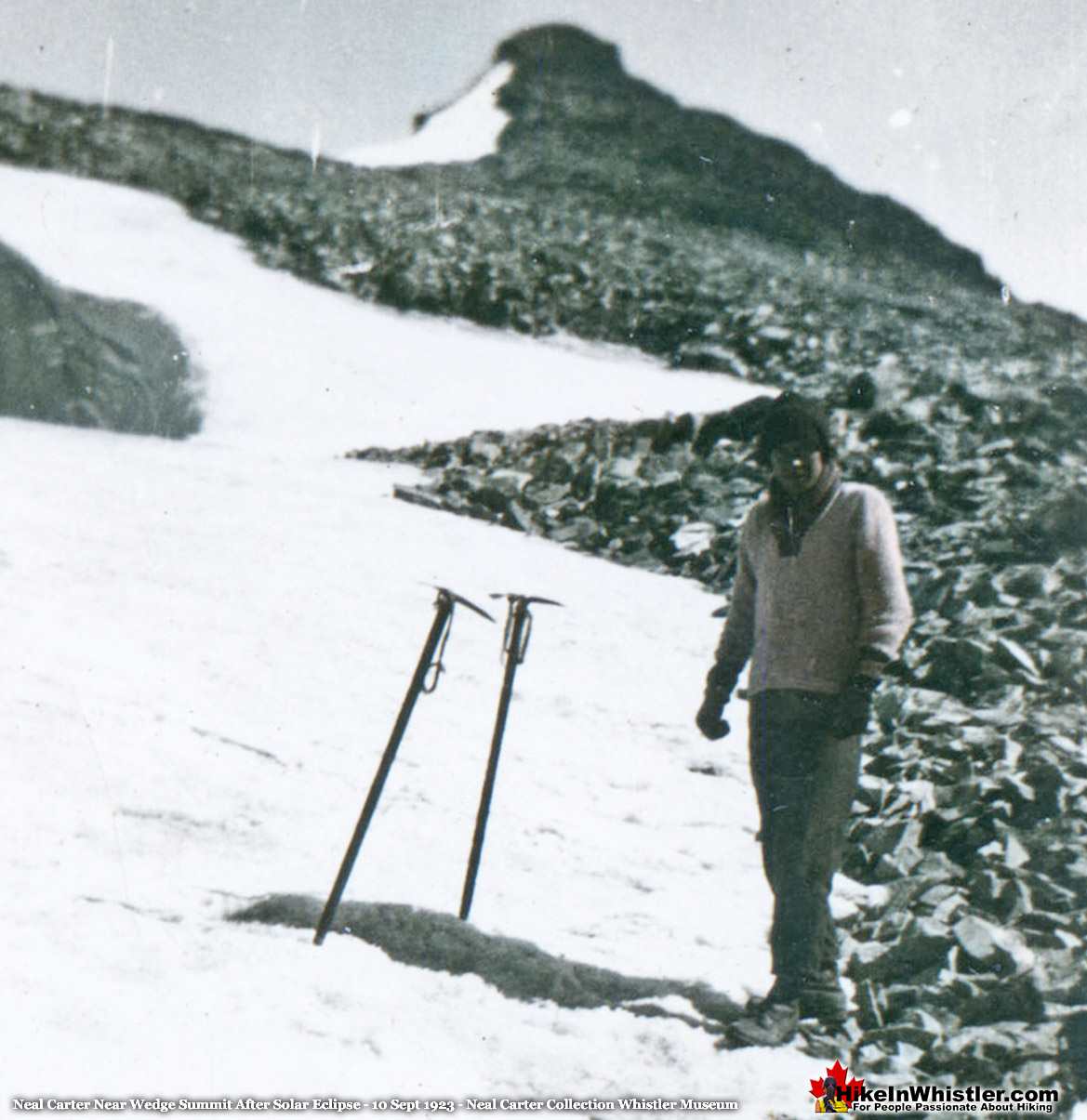

SAW SUN’S ECLIPSE

A summit ridge of elevation 8200 feet was finally reached, culminating in the actual peak, some 200 feet higher at the far end. A splendid view of the partial eclipse of the sun was obtained just before reaching here.

Neal Carter on Wedge Summit Ridge - 10 Sept 1923

Neal Carter Wedge Mountain Summit - 10 Sept 1923

First View of Mt James Turner from Wedge Summit - 10 Sept 1923

Panorama South from Wedge Mountain - 10 Sept 1923

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Wedge Mountain

In 2012, Jeff Slack, working at the Whistler Museum created three wonderful videos of the Carter/Townsend expedition. He used the written account of Charles Townsend and the photos taken by Neal Carter. He narrated the videos along with images from Google Earth, recreating the journey in beautiful detail. This is the first of the three videos, The 1st Ascent of Wedge Mountain - A Virtual Tour, which covers the journey from Rainbow Lodge to the summit of Wedge Mountain.

September 11, 1923: Hike Around Wedge to Camp #2

Following around the face of Wedge, keeping approximately at timberline all the way, we came to the edge of the deep valley behind Wedge and dropped down 800 feet to camp beside a roaring stream coming from a glacier not far above us. A long hot walk along a steep side hill all afternoon with little or no water again made us thankful to lay out the sleeping bag on the heather and play ourselves to sleep.

Carter Looking West to Wedge Mountain - 12 Sept 1923

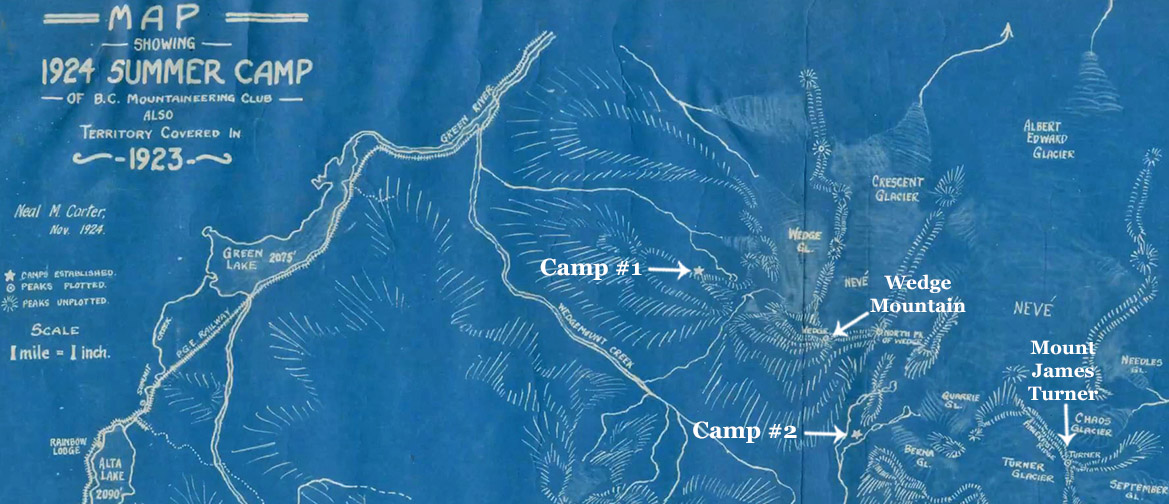

Section of Neal Carter's 1924 Map

In 1924 Neal Carter created the first detailed map of the region that would become Garibaldi Park. His contribution to mapping and surveying the region was enormous and the original Garibaldi Park topographical map created in 1928 was largely based on his exploration and surveying work. This is a small section of his 1924 map showing some details of the 1923 expedition. To make it easier to identify, Wedge Mountain and Mount James Turner have been added to highlight their location on the map. Also Camp #1 and Camp #2 have been added. They are shown on the map as stars. Camp #1 was on Parkhurst Mountain, which was unnamed at the time, which is why Carter and Townsend never identify it. It is interesting to note that Carter's map does not show Wedgemount Lake, which evidently covered by Wedgemount Glacier at the time.

September 12, 1923: Mount James Turner

The summit was finally reached safely about 2pm, and found to consist of a pinnacle of rock hardly large enough to stand on. The mountain is shaped like a tetrahedron, two of whose faces are precipitous and hopeless to climb; the third, up which we came, only slightly less so.

Neal Carter on Mount James Turner - 12 Sept 1923

DEPOSITED RECORD

As large a cairn was built as the peak would support, and a record deposited naming it Mt. Turner, after the Rev. James Turner, a lifelong Methodist church worker who died in 1916 at the age of 74 after rendering many years of faithful service in this province and the Yukon.

Neal Carter Mount James Turner Summit - 12 Sept 1923

The elevation proved to be 8000 feet, and the large glacier we had crossed was named the Turner Glacier. (Turner Glacier is now called Chaos Glacier)

Neal Carter Chaos Glacier & Fingerpost Ridge - 12 Sept 1923

Another huge glacier to the north having a neve of over 8 square miles, we named the Albert Edward. Several others were named, on in particular, consisting solely of one continuous ice-fall, became the Needle Glacier from its numerous ice pinnacles.

September 13, 1923: Camp #2 to Camp #1

Carter skips September 13th in his article, as it was just a move from their second camp back to their first camp on Parkhurst Mountain.

September 14, 1923: Camp #1 to Alta Lake

Carter also doesn't write about September 14th where they hiked down to the Rainbow Lodge for the night. Townsend wrote about the day briefly in his Mountaineer article: "The next day we packed back to our first camp and the day following down to Alta Lake. The latter journey taking six hours. At Rainbow Lodge we had an excellent supper which partially made up for a week of dried goods. Afterwards we collected the other half of our grub preparatory to making an early start the next day up Fitzsimmons Creek."

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Mount James Turner

This is the second of three videos created by Jeff Slack for the Whistler Museum. This one titled, The 1st Ascent of Mount James Turner - Virtual Tour, shows the journey Carter and Townsend went on to reach Mount James Turner. Using Google Earth, Slack follows the route they took, narrates the journey with Townsend's written account, and illustrates it with Neal Carter's beautiful photos.

September 15, 1923: Alta Lake to Fitzsimmons Cabin

Carter's article doesn't include details about their hike up Whistler Mountain on the 15th. Charles Townsend wrote a short description of the day in his BC Mountaineer article: "The following morning, we left Rainbow Lodge at 11am and found the trail up Fitzsimmons Creek was excellent to travel on. But for some exciting moments with wasp nests, we had an enjoyable day's journey to the cabin on the meadows below Avalanche Pass. The two miners we found to be not at home so we made ourselves comfortable in their absence."

September 16, 1923: The Fissile, Refuse Pinnacle and Overlord

On Sunday we made the ascent of Mt. Overlord, second highest in the group, by way of going around the rear of Red Mountain and over a series of pinnacles on the ridge leading up to Mt. Overlord.

Neal Carter on Pinnacles Leading to Overlord - 16 Sept 1923

One in particular on one side was a sheer drop to the Fitzsimmons Glacier hundreds of feet below, while the back was a veritable ore-dump consisting of strips of granite, quartz, slate, iron ore, etc., all broken up into small pieces by the frosts and left in a pile at the “clinging angle”. This we refer to as “Refuse Pinnacle”.

Charles Townsend on Refuse Pinnacle - 16 Sept 1923

Mt. Overlord’s summit closely resembles that of Wedge, and is perhaps a little over 8000 feet. Mr. and Mrs. Munday’s record was found, and ours added to it. The view to the north and south is not so striking.

Peaks from Overlord Looking Northeast - 16 Sept 1923

RETURN IS SIMPLIFIED

After climbing a few odd-shaped pinnacles around the rim of the glacier on Overlord, the return trip was simplified by going around the bottom of the pinnacles beyond Refuse Pinnacle on the glacial neve.

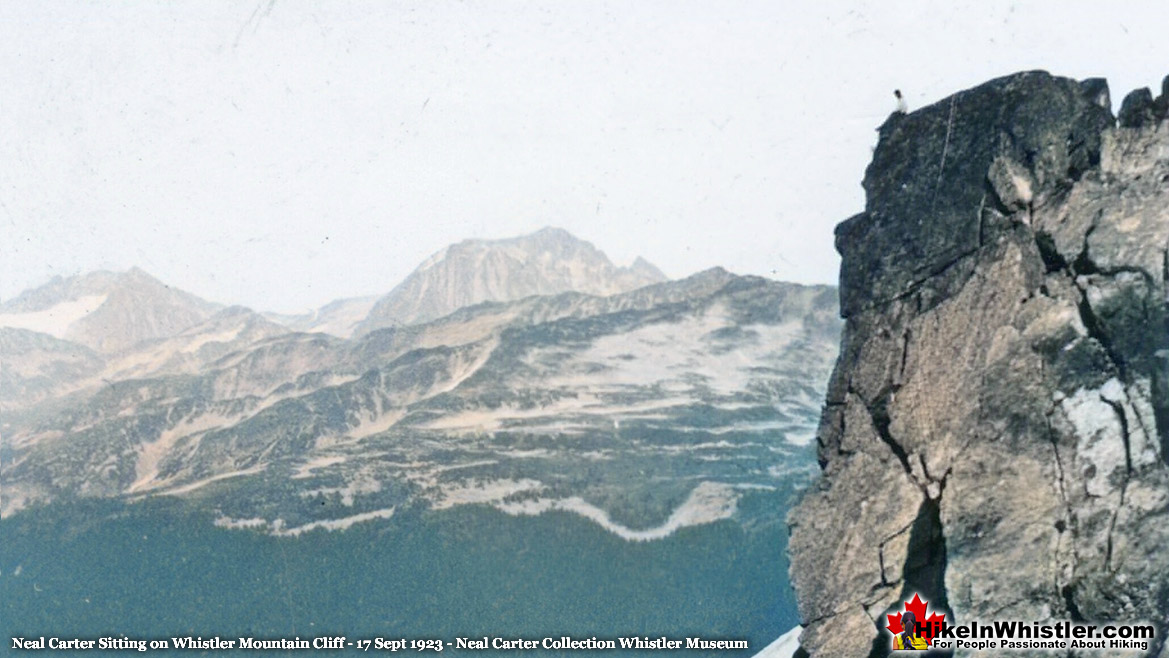

September 17, 1923: Whistler Mountain

Although not a strenuous trip, we decided to take the next day easy and made an ascent of Whistler Mt. from the cabin. This is most easily reached from Alta Lake, which it overlooks, and is frequently ascended from the lodge, and made a pleasant afternoon’s trip..

Neal Carter Whistler Mountain - 17 Sept 1923

September 18, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin to Mount Diavolo

Tuesday the weather showed signs of breaking and we hurried to get in our last trip. From K.M. pinnacle back of Mt. Overlord, I had seen a sharp peak connected to where I was by a knife-edge ice ridge above which a rock arete led to the summit. This was so narrow that sections of it looked as if they could be pushed over, and promised so interesting a climb that Mr. Townsend named it Mr. Diavolo from its black and sinister appearance, and we determined to try this peak today.

CLIMBING IN DANGER

Taking advantage of a momentary rift, a photo was taken and a start made immediately, ice steps had to be cut up the steep ice ridge and when within four steps from the top, my ice-axe cracked and almost broke in two while cutting, very nearly throwing me off my balance and providing rapid transit to the Diavolo Glacier far below. Finishing these few steps with Mr. Townsend’s axe, we stepped onto the rock and began one of the most exciting bits of rock climbing. It is best compared with the summit arete of Mt. Tupper in the Selkirks. Fog hid from us the full extent of the tremendous drops on either side in case a hand or foothold should give away. Fifty minutes later the top of the arete was reached, after a climb of only two or three hundred feet.

Charles Townsend on Ridge to Diavolo Peak - 18 Sept 1923

Here we were much disappointed to find the real summit, a few feet higher, some 50 feet away, connected by a practically level series of knife-edged pinnacles of rock. After some debate in which the lateness of the hour entered into consideration, I started off to work my way along astraddle the ridge, the only indication of Mr. Townsend’s presence behind being a clatter of rocks back in the fog as sections of the ridge would topple over and go avalanching down to the glaciers on either side below. Loosened by me while testing them, he would knock them over to avoid trouble on the return. The summit cairn was finally erected at 2:45 and the name Diavolo heartily verified. Although only 7700 feet in elevation, it amply repaid our search for a rock climb.

Charles Townsend Straddling Diavolo Summit - 18 Sept 1923

On a clear day a wonderful panorama of the mountains around the head of the Pitt River might be obtained, as well as the Cheakamus Glacier, the largest in the region, consisting of one continuous ice-fall from the base of Mt. Castle Towers to almost the level of Cheakamus Lake, 4000 feet below. With the aid of the rope, we negotiated the return safely, and following our footsteps over the fog covered glaciers, made good time by reaching the cabin about 6:30. Soon after in commenced to rain, and the following day was spent inside.

September 19, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin Rain Turned to Snow

We saved food by laying in bed most of the morning reading; however, by night we had almost come to the stage of hiding our food from each other, and if a raisin dropped on the floor, it was a case of get a candle and hunt for it. Snow began to fall in the afternoon, and we awoke next morning to find 2 ½ inches had fallen and part of our firewood, cut in five-inch lengths, packed away under the bed by packrats.

Charles Townsend Outside Fitzsimmons Creek Cabin - 19 Sept 1923

September 20, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin to Alta Lake

So we took the hint and after a somewhat imaginary breakfast, left for Alta Lake. That night we had a real supper at the lodge and after a few hours sleep, caught the early morning train (21 Sept Friday) and arrived back in Vancouver at 10:30 am highly pleased with our mountaineering holiday. Lots of goat tracks seen, but few evidences of bear. Only animals actually seen were marmots and a porcupine at the cabin.

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Mount Diavolo

This is the third of three videos created by Jeff Slack for the Whistler Museum depicting the amazing journey Carter and Townsend went on when they explored the Fitzsimmons Valley to the peaks of Mount Overlord. This one is titled, The 1st Ascent of Mount Diavolo - A Virtual Tour. Using the words of Charles Townsend and the photos of Neal Carter, the video shows the journey with the use of Google Earth.

Charles Townsend's Account of the Expedition

Charles Townsend also wrote about the expedition in two articles that appeared in two editions of the BCMC Newsletter in 1923. The October edition printed, 'Trip to Wedge Mountain and Mt. Turner', and in November, 'Fitzsimmons Creek Mountains'. They, along with more of Neal Carter's photos can be found here. The wonderful videos above from the Whistler Museum are narrated directly from Townsend's articles.

1924: Climbing in the Tantalus Range

Neal Carter, Hazen Nunn, Ted Taylor, Art Cooper & Fred Smith

In the spring of 1924 Neal Carter set out on his second expedition into the Tantalus Range with Hazen Nunn, Ted Taylor, Arthur Cooper and Fred Smith. Mount Tantalus was their main goal, however, deep springtime snow, bad weather and difficult route finding barred their attempt. Despite not reaching the summit of Tantalus, the expedition reached the summits of several other prominent mountain peaks, such as Alpha, Pelops, Dione and Omega. Along the way they named several unnamed mountains in keeping with the Greek myth of Tantalus. Niobe, Pelops, Dione, Sisyphus and Pandareus are all names created by Neal Carter, Hazen Nunn, Ted Taylor, Art Cooper and Fred Smith in 1924. Carter's beautiful photo album of the expedition is now at the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. Hazen Nunn wrote about the 1924 Tantalus expedition in the BC Mountaineer in June of that year. His detailed account along with Carter’s photo album recall this fascinating expedition into the Tantalus Range. The following is Hazen Nunn’s article with images and captions from Neal Carter’s photo album added. Most of the photos have been partly colorized to try to bring the original black and white images more to life. Date headings have also been added to Nunn's article.

In the spring of 1924 Neal Carter set out on his second expedition into the Tantalus Range with Hazen Nunn, Ted Taylor, Arthur Cooper and Fred Smith. Mount Tantalus was their main goal, however, deep springtime snow, bad weather and difficult route finding barred their attempt. Despite not reaching the summit of Tantalus, the expedition reached the summits of several other prominent mountain peaks, such as Alpha, Pelops, Dione and Omega. Along the way they named several unnamed mountains in keeping with the Greek myth of Tantalus. Niobe, Pelops, Dione, Sisyphus and Pandareus are all names created by Neal Carter, Hazen Nunn, Ted Taylor, Art Cooper and Fred Smith in 1924. Carter's beautiful photo album of the expedition is now at the MONOVA Museum in Vancouver. Hazen Nunn wrote about the 1924 Tantalus expedition in the BC Mountaineer in June of that year. His detailed account along with Carter’s photo album recall this fascinating expedition into the Tantalus Range. The following is Hazen Nunn’s article with images and captions from Neal Carter’s photo album added. Most of the photos have been partly colorized to try to bring the original black and white images more to life. Date headings have also been added to Nunn's article.

BC Mountaineer No.4, Vol. 2 JUNE, 1924

CLIMBING IN THE TANTALUS RANGE

By E. H. Nunn

Saturday, May 10th, 1924

Our party, consisting of Neal Carter, Ted Taylor, Arthur Cooper, Fred Smith, and myself, left on May 10 for Squamish to spend a week in the Tantalus Range. Leaving the boat, we learned that Barber's Camp on the Squamish River was not operating, so had to abandon the idea of camping at 5,000 feet and proposed to make camp instead at Tantalus Lake or the “Lake of Lovely Waters”, at 3,700 feet. We got to Chee Kye at 4.30 and a hike of about two miles brought us to the Squamish River where we made our first night’s camp. The beauty of a perfect moonlight night was somewhat marred by armies of husky mosquitoes who attacked us on all sides, and we retired early to our sleeping bags,--two to a bag, the advantage being of less weight to pack and of added warmth, although the prominent features of one’s anatomy are somewhat accentuated.

Sunday, May 11th, 1924: Hike to "Lake of the Lovely Waters"

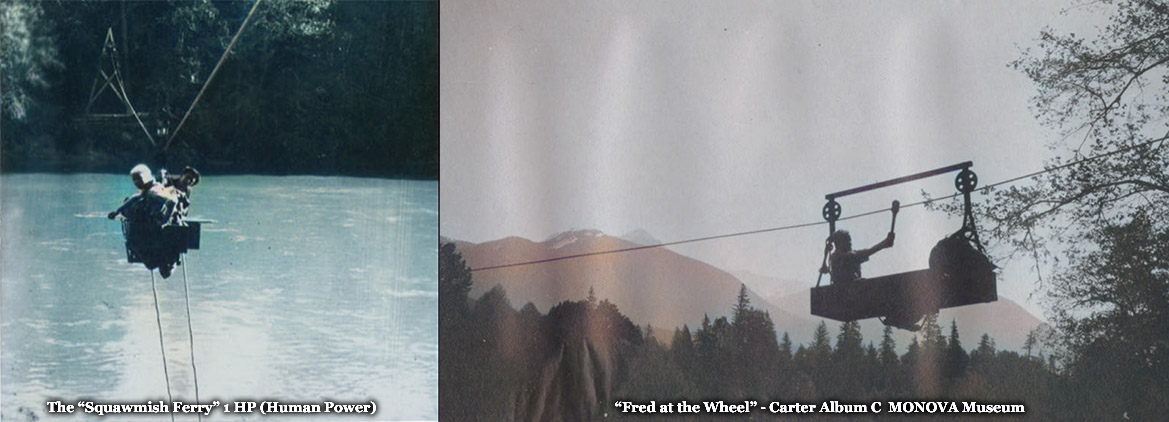

At 5:30 am we beheld the sun rising over Garibaldi, and to the west our Tantalus peaks swimming in a sea of molten gold. Hurriedly eating our breakfast, we cached some grub and crossed the river by the cable near our camp.

Squamish River Cable Car Crossing - 11 May 1924

From here we lunged into virgin forest and pushed our way through underbrush and over fallen timber until, at 12:30, we emerged at the creek which drains the lake. We were now only at 1,000 feet, but from this point on, the going became better. Ascending a rock-slide for 1,000 feet, we hit the snow line (3,100) at 4:30. Here the going became better still and we were soon on the ridge in view of the lake. Finding no bare ground, camp was made on the snow. We retired early in anticipation of a good day’s climbing on the morrow.

"Lake of the Lovely Waters" Camp - 11 May 1924

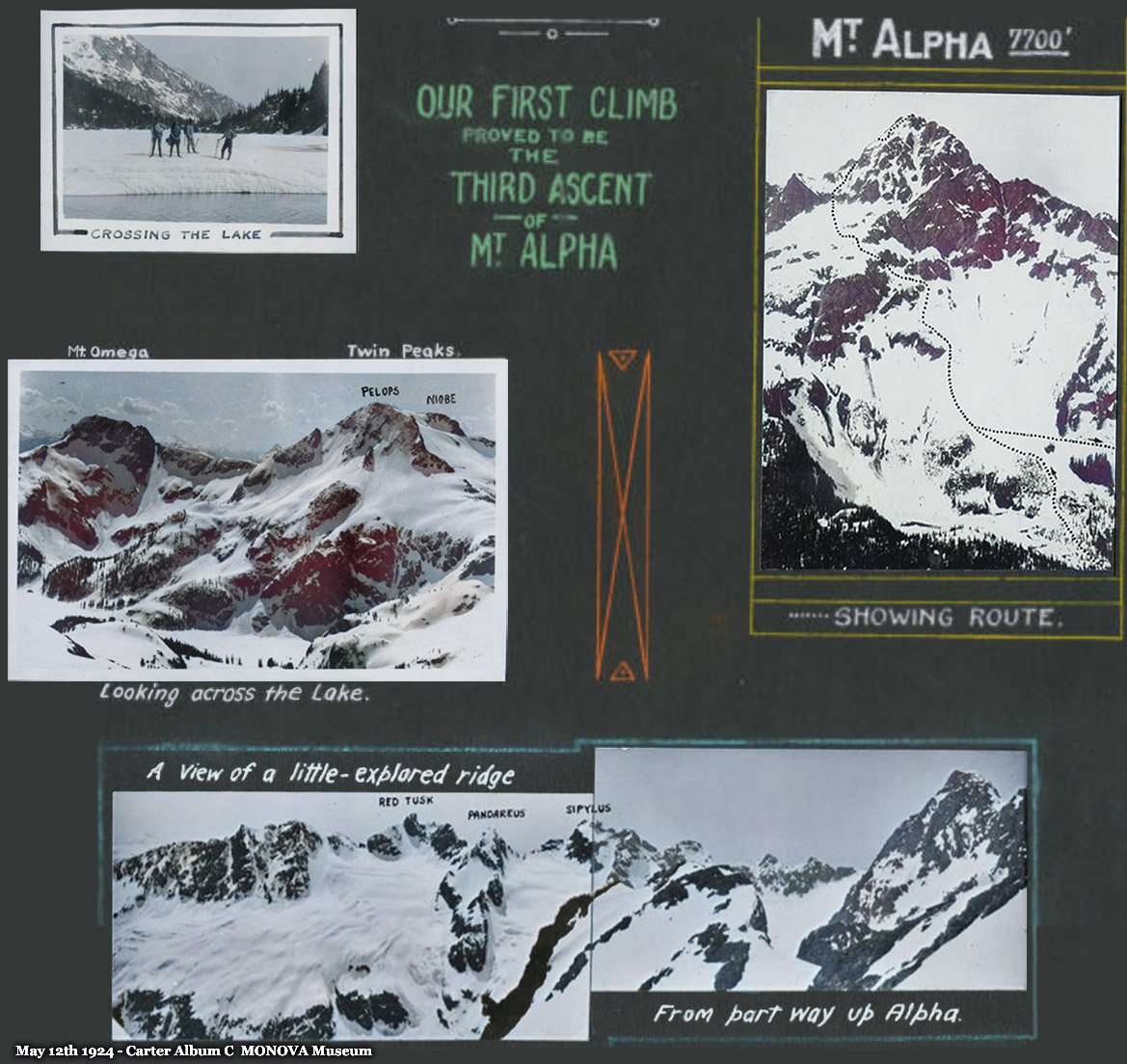

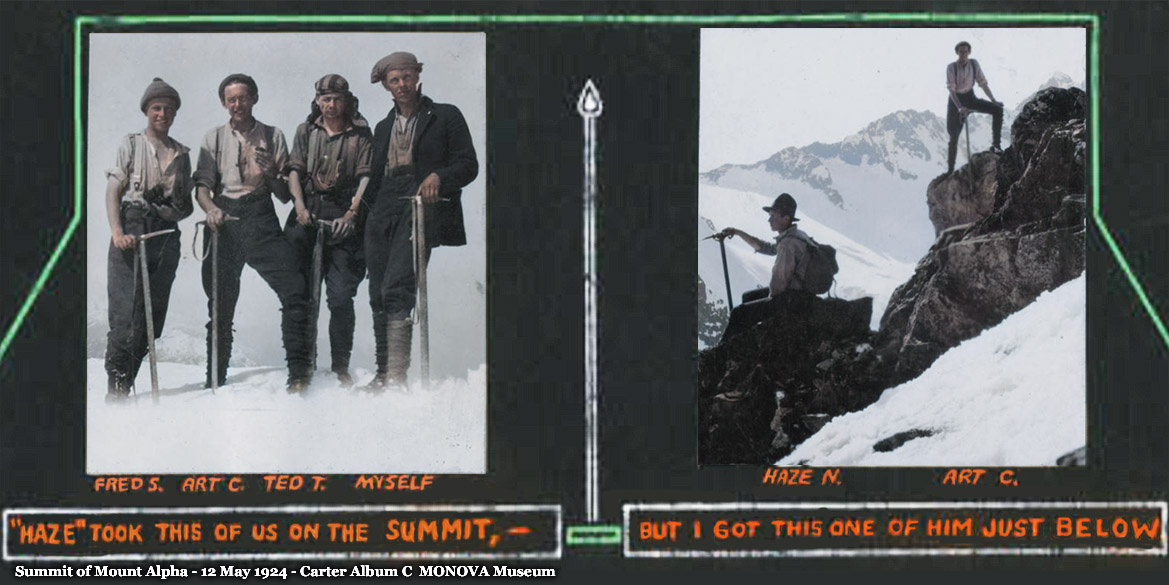

Monday, May 12th, 1924: Mt. Alpha

Leaving camp at 8:30 Monday a.m. we hiked down the frozen lake to a favourable point and commenced the assault on Mt. Alpha. A few preliminary snow slopes brought us to the scree-covered ledges of the main peak. To the west lay the serrated crags and pinnacles of the Red Tusk Ridge, dominated by Mt. Serratus itself. From this ridge a series of glaciers flow eastward toward the lake, each terminating in an ice-fall, from which came almost a continuous roar as tons of rock and snow poured over the cliffs.

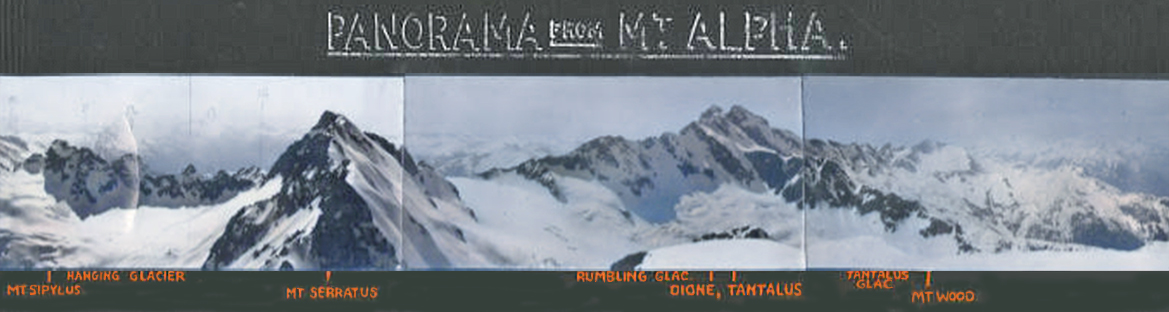

Alternating between interesting rock work and steep snow slopes, we passed the last vestige of vegetation at 11:30 (6,400). At this point we were surprised by an avalanche which swept down the slopes not twenty feet from us and went thundering down over the cliff. The rock ledges were covered with a lot of loose rocks, and the rear climbers were kept busy dodging the fusillade. Suffering no casualties, we arrived on the corniced summit at 1:50 and found in the cairn a record to the effect that A.B. Morkill and B.S. Darling had made the first ascent in 1914, and that Tom and John Fyles had climbed the peak in 1916. Ours was the third ascent and the earliest. Observations on two aneroids gave and elevation of about 7,700 feet. Lunch and the wonderful view were absorbed simultaneously and made a good combination. To the east lay the Garibaldi group, with the cairn on The Table visible with the naked eye. With the aid of our field glasses, though, some of the more obscure details were easily recognized. To the north we could see Wedge Mt, and Mt. Turner. Behind us, to the south, lay the local peaks with Mts. Crown, Bishop, Cathedral and Brunswick plainly visible—the Sawteeth also showing up well. To the southwest reared the imposing massif of Mt. Sir Roderick, and in the further distance rose the Jervis Inlet peaks. On every hand stretched an endless ocean of snowy pinnacles and billowy ridges,—material to reward the efforts of exploration for many years to come. In the valley, 7,500 feet below us, lay the thread-like Squamish River, and the tiny villages of Chee Kye and Brackendale.

"Our First Climb" Mt. Alpha - 12 May 1924

Tantalus Range Peaks Named

Mts. Alpha and Omega (also known as the South Peak), are visible from the Squamish Valley and are well known by name. We suggested a number of new names from the Greek myth of Tantalus. Thus the N. and S, Twin Peaks we called Niobe and Pelops, while the two main peaks of the range we named Tantalus and Dione. Two prominent pinnacles in the Red Tusk Ridge we called Sisyphus and Pandareus.

Mt. Alpha Summit - 12 May 1924

Panorama From Mt. Alpha - 12 May 1924

Fred Smith, Ted Taylor & Arthur Cooper Mt. Alpha - 12 May 1924

At 3.30, having taken some plane-table observations for a map of the district, we left the summit, and after an exhilarating descent arrived on the lake at sunset. In this vicinity we noticed several areas of red snow. The lake was a bit slushy, and every step was a knee-deep plunge. We arrived back in camp at 6.25, and a victorious attack was made on the macaroni and cheese.

Tuesday, May 13th, 1924: View Rock, Pelops & Niobe

Tuesday morning, we left at 9.15 and crossed the lake towards the southern peaks. Ascending a snow gully, we emerged into a glacial amphitheatre filled with avalanched debris. From here an hours grind up the north margin of the snow covered glacier brought us to the neve. In places the wind had blown the snow away, exposing the blue and green ice. In front of us rose the Twin peaks,—Pelops and Niobe; behind us towered Omega, and to the north loomed the imposing mass of Alpha. On our left we noticed a small, but promising looking, rocky peak. (View Rock, now officially named Mt. Iota).

Route Up Pelops and Niobe - 13 May 1924

View Rock (Mt. Iota) Summit

By noon we had gained the summit and found that Smith and Warren had made the first ascent in 1910. Mt. Sir Roderick looked very impressive from this point and we could also see that the route in to the Tantalus district by Mill Creek would be impracticable as two ridges of about 5,500 feet altitude would have to be crossed and the deep intervening valley would make packing in difficult.

"The Three Musketeers on the Rock" (Mt. Iota) - 13 May 1924

Mount Pelops Summit

Dropping down again to the neve, we ascended Mt. Pelops by a series of snow slopes broken by jutting rock ridges. Finding no cairn on the summit we left evidence of the first recorded ascent, and observed the elevation to be about 6,800 feet, and that of Mt. Dione Mt. Niobe (Nunn incorrectly wrote Mt. Dione instead of Mt. Niobe) to be slightly lower. On the ridge between the two Twin peaks we found a fine example of a wind cirque which showed the depth of snow to be about 40 feet.

"A Tremendous Wind-Sweep Between Pelops and Niobe" - 13 May 1924

Mount Niobe Summit

By 2:40 we were on Mt. Dione Mt. Niobe (Nunn incorrectly wrote Mt. Dione, they were on Mt. Niobe) and found a record stating that Smith and Warren had climbed the peak in 1910.

Mount Omega Summit

Leaving at 3.15, we glissaded down to the neve and, traversing below the cliffs of Pelops, crossed the snowfield towards Mt. Omega. An interesting rock scramble brought us to the summit at 5.15. There was a cairn with no record, but we recently learned that it had been built by Tom Fyles in 1916.

"Mt. Omega from the Rock" (Mt. Iota) - 13 May 1924

The view from the peak was almost as fine as from Alpha. The sun was getting low and the peaks threw their shadows for miles across the snowfields and glaciers. The bases of the crags and their ridges lay in the soft purple shadows of twilight, but the summits still flamed with the fiery splendor of the sunset. The tremendous ice-fall of the Chee Kye glacier on the west face of Garibaldi looked especially fine where the level rays of the sun brought out the vivid blue and green in the ice, contrasting with the red volcanic rock. We left Omega at 5.45, and after scrambling down the rocks, glissaded back into the amphitheatre. From here a short hike across, or more properly, through, the lake brought us back to camp.

Wednesday, May 14th, 1924

Wednesday dawned cold and cloudy, so we stayed in the vicinity of the camp all day.

Thursday, May 15th, 1924

Thursday was another dull day so we broke camp quite early and left the Lake of Lovely Waters at about 10. Following our route in over the rock-slide we arrived at the creek at 1.45 and found the water much higher. We finally managed to cross, however, and followed the ridge down to the Squamish River. A hike of about two miles along the west bank landed us back at the cable and we were not delighted to find the car on the wrong side. The situation was saved, however, by Neal, who made a rope sling and hauled himself across, At 7.30 we hit the Cheakamus River and made camp.

Friday, May 16th, 1924

Leaving Chee Kye at 9.30 a.m. Friday we started the ten-mile hike to Squamish, but fortunately got a lift for six miles. An enjoyable trip down the Sound landed us in the city at 5.30.

Fred Smith, Hazen Nunn, Art Cooper, Neal Carter & Ted Taylor

1925: Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus

Neal Carter, Charles Townsend & Hazen Nunn

Tantalus Range as we now know it was barely explored when Neal Carter set his eyes on it in the spring of 1923. All the colorful names we use today were not yet created. The range was dubbed Tantalus Range in the years previously and the tallest, most prominent peak became Mt. Tantalus. Another prominent peak climbed in 1914 was named Alpha by Basil Darling. Omega, Pelops, Niobe, Serratus, and many more were still unnamed peaks. Carter summarized the brief history of early exploration of the range.

Two of the lower summits of the eastern end of the range were ascended in 1910 by a party led by Mr. G.B. Warren. The first account of a mountaineering trip to this range is found in the 1912 Canadian Alpine Club Journal, in which Mr. B.S. Darling of the B.C. Mountaineering Club, relates his exciting experiences in leading a party on the first ascent of Mt. Tantalus in July, 1911. Mr. Darling revisited the region in July, 1914, making the first ascent of Mt. Alpha (7700 feet), which was again climbed in August, 1916, by Mr. Tom Fyles, present director of the B. C, Mountaineering Club, in company with his brother. The latter party also made the first ascent of the lower of the two peaks of Mt. Tantalus.

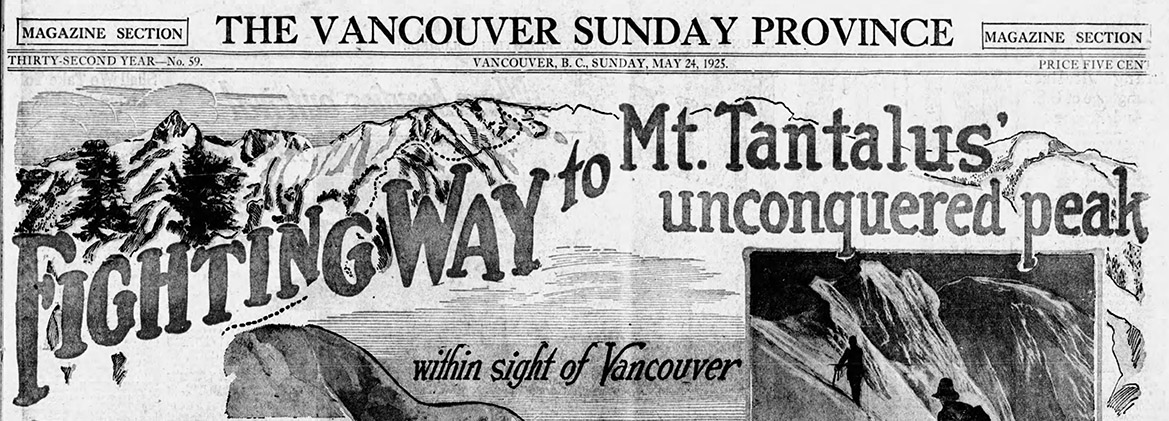

“Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus’ Unconquered Peak”

On Sunday, May 24th, 1925 the Vancouver Sunday Province had a feature article titled, “Fighting Way to Mt. Tantalus’ Unconquered Peak”. The article was written by Neal Carter just a few days after his third expedition into the Tantalus Range. Three years in a row in springtime he ventured into the challenging and fairly unknown mountain range. This third expedition by Carter, he was joined by Chas Townsend and Hazen Nunn. Townsend was with Carter on his first expedition in 1923 and later that year he and Carter went on their incredible expedition into the unknown mountains around what is now Whistler. Hazen Nunn accompanied Carter on his second expedition into the Tantalus Range in 1924. The highly skilled trio were very motivated and had the ability to reach their goal as Nunn later wrote:

The Tantalus Range runs in a general North-West direction from Howe Sound and can be seen to advantage on the way to Squamish. Although not so extensive as the neighbouring Garibaldi group, it is much more rugged and precipitous. The peaks rise abruptly from the valleys to imposing heights. Mt. Tantalus, the highest peak, overlooking Garibaldi itself. The object of this year’s expedition was to climb Mt. Tantalus which lies in the northern part of the range.

Their 1925 expedition to conquer Mt. Tantalus was unsuccessful, however the expedition was wildly successful in an unexpected way. The photos they took and the articles they wrote bring the historic adventure to life in a beautiful way. It is extraordinary to see a photo of an alpine summit taken a century ago. Photos back then were rare enough, but from a snowy summit after a brutal trek. Extraordinary. The following is the account of the Tantalus expedition in the spring of 1925, mostly taken from Neal Carter's Vancouver Sunday Province article and Hazen Nunn's BC Mountaineer article, both written in 1925.

Day 1: Vancouver to Squamish River Camp

The first day was spent travelling from Vancouver to their first nights camp along Squamish River. From Vancouver to Squamish they travelled by boat ferry. From the boat dock in Squamish they then travelled 30 kilometres by “auto stage” to Chee Kye, a small settlement along Cheakamus River just upstream of the point where it joins Squamish River. They next had to get across Cheakamus River which Carter described, “..by employing “Indian Jim” to take a dugout canoe up the Squamish from Chee Kye, we could cross at the advantageous place used two years previously.” They then made their way to their first camp Hazen Nunn referred to as “Barber's abandoned lumber camp on the south bank.” This camp was in an ideal location leading to what Carter described as “a prominent ridge which led right to the heart of the highest part of the range.”

Day 2: Difficult Hike to Alpine Camp

The next morning, they began the difficult hike up the ridge through dense underbrush and swamp and which Carter described as an “African jungle”. After an hour of difficult bushwhacking, they emerged to more open terrain along the ridge which ascends steeply in a series of bluffs. Carter estimated, “..progress was made at the rate of 1500 feet elevation per hour in places.” Several hours later they reached their second nights camp. Carter wrote, “Towards the end of the day, however, the exertion began to tell, and packs were dropped with much relief at a suitable spot just below the summit. The depth of the snow was estimated at fifteen to twenty feet, and much difficulty was experienced with camp fires, which persisted in eating their way down to a considerable depth, when a fresh one would have to be built. All water was laboriously obtained by melting snow.”

Neal Carter and Hazen Nunn Tantalus Camp - April 1925

Day 3: Attempt on Mt. Tantalus

The third day of the expedition they woke early to climb Mt. Tantalus. Carter detailed the challenging day in detail.

The weather was splendid for an early start the next morning to Mt. Tantalus. The hard snow experienced along the connecting ridge gave way to the soft dry powdery variety when the head of the glacier to the right was reached, however, and it was soon realized that the peak would never be climbed that day. But by plugging along as far as possible, a trail could be made which would enable the ascent to be completed the following day. This was done, therefore, and proved quite dangerous. The party had to rope together, for the glacier is notoriously steep and broken in summer, which means that in spring a light covering of snow hides innumerable hidden crevasses. Many of the larger crevasses were already open, and occasioned much trouble in choosing a route.

Neal Carter, Hazen Nunn, Alpha & Serratus Mountains - April 1925

Hazen Nunn continues the story.

Leaving the ridge, we traversed below a series of cliffs and roped up on the margin of the glacier. A peculiar feature of Tantalus Glacier is a nunatak rising some 200 feet above the ice. This rocky pinnacle, which, owing to its shape, we called the Horn, is situated below the peak, and our course was directed towards it. At 2:30 we reached it and found the altitude to be 7,300 feet. As the peak was known to be at least 1,000 feet higher, we decided, in view of the exhausting trail breaking, to renew the attempt the next day.

Nunn, Townsend & Carter "Flashlight of the 1925 Party"

Day 4: Second Attempt on Tantalus

On day 4 they set out on their second attempt to reach the summit of Mt. Tantalus. Carter described the day.

With greater hope of success, a fresh attempt was commenced the following morning and splendid time made over the already broken trail. In places, wind-drifted snow had filled it overnight, but the "Horn" at 7000 feet was reached over two hours earlier than before. From here the ascent lay up a tremendous steep slope of soft snow to a pass just below the peak; but many hours were spent battling with the crevasse stretched completely across between cliffs of the peak on one side and a rocky inaccessible ridge on the other. It looked as if progress was barred but, fortunately, a narrow ridge of snow at an angle of 45 degrees was left unmelted, and over this the party crossed with much misgiving. Once over the top of the pass a wonderful view was obtained of the country to the south between the head of Jervis Inlet and Howe Sound. The peak could be seen rising some 500 feet higher to the left, and since there seemed to be no immediate difficulty, our hopes of success were high.

Neal Carter & Hazen Nunn Approach Tantalus Summit - April 1925

Half an hour later, however, it was discovered that a narrow ridge of overhanging snow lay just in front of us, separating the summit by some 200 feet linear distance. It was deemed imprudent to attempt to cross this, for if it gave way during the process, a 6000-foot drop to the Clowholm Lakes on one hand and a 1000-foot drop to the head of the Rumbling Glacier on the other would have been sure to have put our aneroid out of order. Hence one of the most galling events had to be endured; that of stopping short of the summit. Our elevation was 8800 feet and the summit about seventy-five feet higher.

Hazen Nunn wrote about the beautiful view from the summit ridge.

From the summit ridge a wonderful panorama was enjoyed in all directions. Almost directly below us lay Clowholm Lake and Narrows Arm. This locality was once proposed as the site of a summer camp, but we could see that the peaks are not as imposing as was thought at that time. To the north lay the vast dissected coast peneplain reaching far up into the Lillooet country. The whole length of the Squamish valley could be seen, and the river followed from its headwaters down its winding course to the sea. We had a very fine view looking down on the Garibaldi range, and various features in the 1924 summer camp district were recognized.

Charles Townsend & Hazen Nunn Tantalus Summit Ridge - April 1925

Tantalus Summit Ridge Panorama - April 1925

1932: Mount Meager Expedition

Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram

The Mount Meager massif is a collection of volcanic peaks that can be seen in the distance, to the west of Pemberton Valley, 150 kilometres north of Vancouver. Mount Meager produced the largest volcanic eruption in Canada in the last 10000 years when it had a huge eruption 2400 years ago. In recent years it has produced another type of hazard, debris flows. The last one happened in 2010 when more than 48 million square metres of debris cascaded down from Capricorn Glacier. It was the largest debris flow ever to occur in Canada. In 1932 Neal Carter, Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish and Mills Winram went on a two week expedition into the mountains at the source of Lillooet River. Two years previously Tom Fyles caught a distant glimpse of the unexplored peaks from Gargoyle Peak. Fyles described the area of ice and snowfields far exceeding that of the Columbia Icefield. The 1932 expedition was photographed and Neal Carter wrote a detailed article, ‘Exploration in the Lillooet River Watershed’ in the 1932 edition of the Canadian Alpine Journal. This is the article Carter wrote which details their amazing journey into the unknown. Date headings in blue have been added for clarity. The black and white photos from the article have also been added and some have been colorized a little or a lot.

EXPLORATION IN THE LILLOOET RIVER WATERSHED

By NEAL M. CARTER

That section of the British Columbia Coast range of mountains which covers the 1500 square miles between latitudes 50°30’-51°00” and longitudes 123°30°-124°30° is practically unknown from a mountaineering standpoint. Large scale maps of the Coast utilize this area for title and legend, which, in an alpine region is a direct invitation for exploration.

Parties which have penetrated comparable watershed areas such as the Mt. Waddington district and the mountains north of Bute inlet have shown that such exploration is well rewarded by the finding of peaks of unexpected height and panoramas of snow and ice reminiscent of the last throes of an ice age. The possibility of similar surprises in the region just described seemed quite likely in view of the fact that it is known to feed four large glacial rivers; the Southgate flowing into Bute inlet, the Toba emptying into Toba inlet, the Lillooet which joins the lower Fraser River, and the Elaho, a main tributary of the Squamish flowing into Howe Sound.

Distant views of this region had been obtained by Mr. T. Fyles’ party which ascended Gargoyle Peak in 1930 and by Major F. V. Longstaff’s party when at the headwaters of the Bridge River. The latter reported that the area of ice and snowfields seen far exceeded that of the Columbia Icefield. Four members of the Club, Messrs. Tom Fyles, Alec Dalgleish, Mills Winram and the writer, discovered a fortnight of coincident holidays in August of this year and decided the occasion was opportune for investigating what lay behind this tantalizing skyline which all had seen from some angle or other.

August 8th, 1932 Day 1: Vancouver to Pemberton

Leaving Vancouver on the morning of August 8th, the ever pleasurable journey by boat to Squamish and past Garibaldi Park on the P.G.E. train brought us late that afternoon to Pemberton, where the railway crosses the Lillooet river. It was up this river that we had decided to journey in our effort to reconnoiter the high peaks on the watersheds at its source. Twelve miles upriver by auto left us at a farm near the edge of civilization, where we literally “hit the hay” for the night.

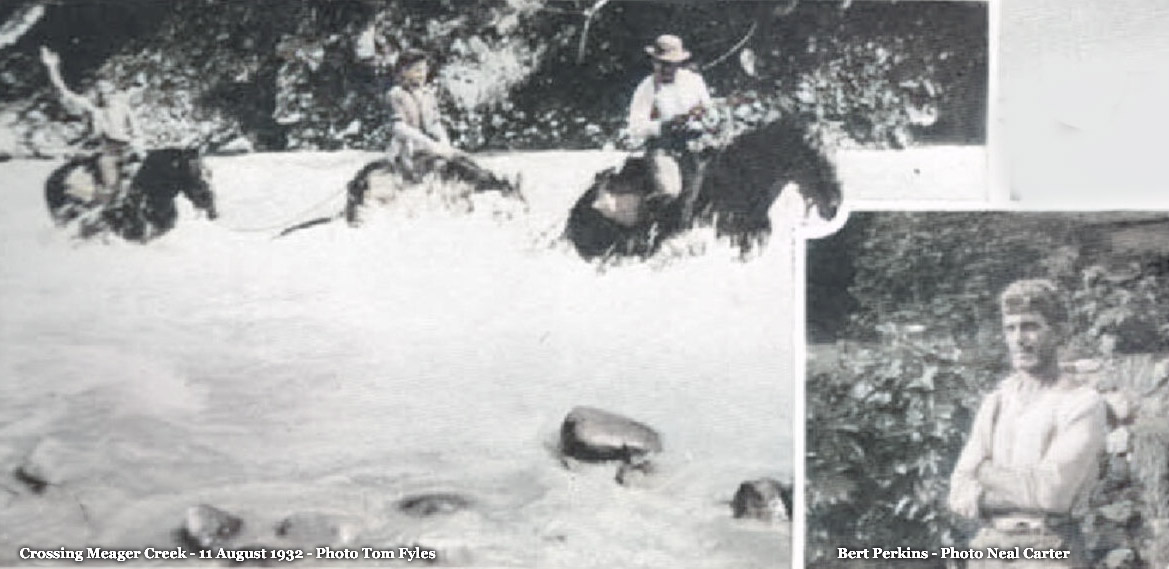

August 9th, 1932 Day 2: Bert Perkins

Next morning, we placed ourselves in the care of one Bert Perkins, trapper of marten and packer extraordinary. What Bert didn’t know about the river systems of this part of the country wasn’t worth knowing, but he confessed that neither he nor anyone else could state what lay above and between the Lillooet and Toba rivers. If we would point out where we wished to go, however, he promised to do his best to get his three horses and our packs as far up as possible, and he did!

For twenty more miles up the south side of the Lillooet River we travelled over trail, swamp, gravel bar and quicksand, stopping overnight at a small cabin near South creek. The Lillooet changes its course so frequently that settlement of its wide and fertile upper valley has been found impracticable, much to the sorrow of some who made the experiment. Near the confluence of several of its tributaries the main stream had shifted since Bert’s last visit and we were left to negotiate delightful beaver swamps and devil’s club thickets while he waded channels with the horses. Occasionally an ice-cold, raging torrent with its load of water-borne boulders would prove too much for us on foot and the pack-horses would be requisitioned as ferries. Because of the steep sides of the main valley, very little of the surrounding mountains could be seen; our attention being chiefly centered on two peaks which lay far up the valley in the approximate position given for Meager Mt., the only named mountain shown on Government maps of this vicinity.

Mills Winram, Alec Dalgleish, Tom Fyles and Neal Carter

August 10th, 1932 Day 3: Meager Creek

By three o’clock in the afternoon of August 10th we reached Bert’s winter trapping headquarters, a well-equipped cabin some two miles below the junction of Meager creek, or south fork of the Lillooet. Here, at an elevation of approximately 1200 feet we paused to take in our surroundings. A wonderful stand of huge red cedars made the area almost park-like, a pleasing variation of the succession of nondescript forest types we had encountered. Besides cedar, the Lillooet valley supports a certain amount of cottonwood, white pine, Douglas fir and hemlock; the undergrowth consisting chiefly of snow bush, elderberry, devil’s club, high bush cranberry and young willow and alder. At higher elevations the cotton-wood and cedar give way almost entirely to the amabilis and Douglas fir and hemlock, which in turn is replaced by the usual alpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) intermingled with wild rhododendron.

It was now necessary to decide from what direction we should approach our objective, tentatively chosen as the group of peaks lying between Meager creek and the Lillooet. Only by climbing to some vantage point could this question be settled. So up we went, taking only our sleeping bags and overnight provisions, after promising to return by ten o’clock the following morning to allow Bert to get us across Meager Creek before the afternoon high water. A steep ridge immediately behind the cabin provided good going and by 8 p.m. we crossed timberline at 6000 feet and made camp after a fashion.

August 11th, 1932 Day 4: Beyond Meager Creek

Early next morning Fyles and Dalgleish crossed a glacier and ascended an 8000-foot rocky peak, while Winram and myself remained on the lower ridge where we established the first camera station of the photographic survey which had been planned by the writer. Unfortunately, rising mists from the valleys obscured much of the view. The general direction of the higher mountains was ascertained, however, and after a headlong descent of the steep ridge we reached the cabin on time and were able to inform Bert that our route appeared to lie up Meager Creek. That afternoon the southeast bank of the creek was followed until a cut-bank forced a crossing. The horses experienced considerable difficulty in finding a footing among the rolling boulders of the stream bed and we had some misgivings as to the condition of the river on our return, should the weather clear up and become hot. Bert’s little dog “Scotty” which we had met at the cabin got left behind here, since he refused to swim the torrent and the horses were not equal to an extra return trip for him. Some three miles up the creek, camp was pitched for the night.

Crossing Meager Creek - 11 August 1932

August 12th, 1932 Day 5: Hot Springs

On the morning of August 12th, the toe of a likely looking ridge at an elevation of 1750 feet opposite some hot springs on the bank of the creek was reached. Here we expected Bert would leave us with his blessing, to return six days later. But not Bert. He disappeared for a while and returned with the news that he thought he could get the horses up that ridge. It was a mighty task; but windfalls, hornets, rhododendron bush and rock slides were slowly left behind (except in the case of the hornets) and a camp finally established on a flower strewn bench just at timberline (5665 feet).

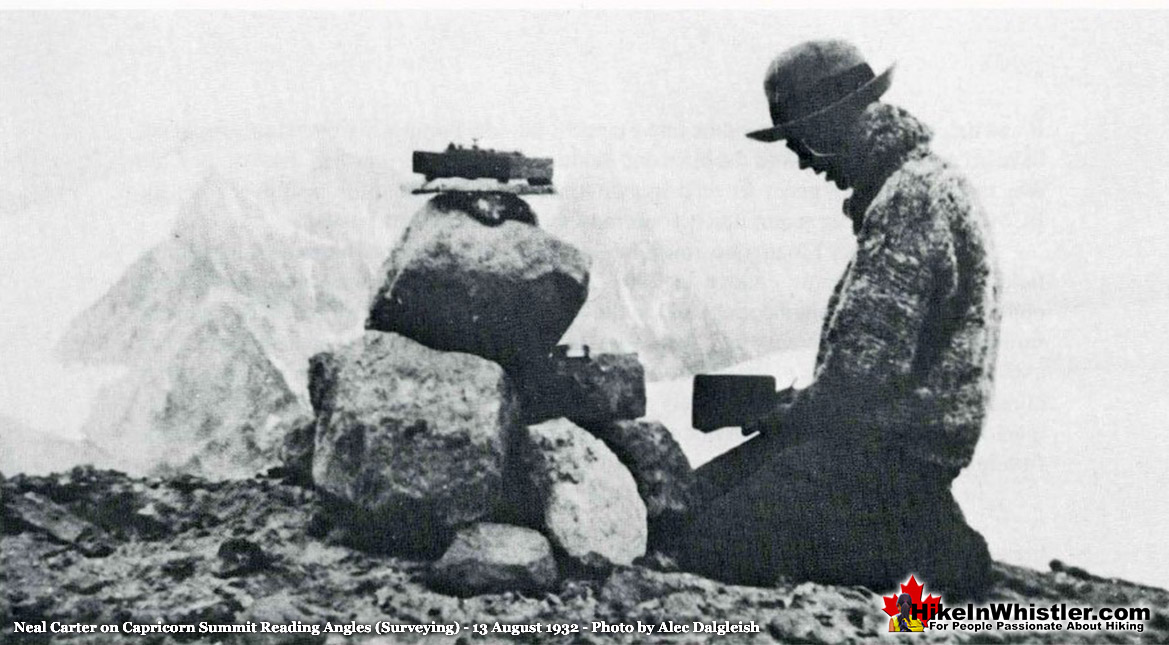

August 13th, 1932 Day 6: Mt Capricorn

The weather for our first climbing day was disappointing and only four days’ climbing was available. With no definite knowledge of how our ridge was connected with the high peaks we had seen two days previously, we decided to tackle the foggy heights immediately behind camp. The ridge grew more arête-like and on a sharp pinnacle of rock we halted for a bite to eat at 7850 feet, hoping the fog might lift. When it eventually did, pinnacle after pinnacle appeared dimly before us, each higher than the last, until we wondered when the procession would cease. It was soon evident that we had chosen the wrong approach to the high, rocky pyramid in which our ridge culminated, so retracing our steps we descended to a glacier below and skirted the base of the ridge. This glacier proved most tractable in providing a fine crevasse-free bench which was to become a necessary matutinal and evening promenade each day as the easiest route to the mountains beyond.

Projecting from a snowy dome at the head of the glacier was a most startling series of grotesque pinnacles of rock. Here we spent an hour waiting for the fog to lift, climbing the more solid towers and inspecting three remarkable rock “windows” which pierced the base of one mass. We named this group “The Marionettes” from their diversity of form. The generally volcanic nature of the region justifies the belief that they are the remains of a volcanic rim, a most interesting vertical section through breccia, basalt and fused ash containing nodules of banded quartz being visible.

The fog had now lifted but the dullness of the day did not encourage an attempt on the rocky peak which rose above us, accessible apparently only by means of a steep snow couloir. We accordingly descended 700 feet to a snow pass and made the first ascent of an easy, snowcapped summit which gave us our first glimpses of the lay of the land. Swirling clouds discouraged a prolonged stay and we left the summit confident that we now knew how to best utilize our three remaining climbing days. The name chosen later for this 8440-foot mountain was Mt. Capricorn, a variation of the all-too-common appellation “Goat” applied by Bert to the stream which drains the Capricorn glacier at its base. A lusty shout before commencing an exhilarating 500-foot glissade down a snow bank just behind camp informed Bert that it was time to put on the kettle, and we retired to the accompaniment of pattering raindrops.

Neal Carter on Capricorn Summit Surveying - 13 August 1932

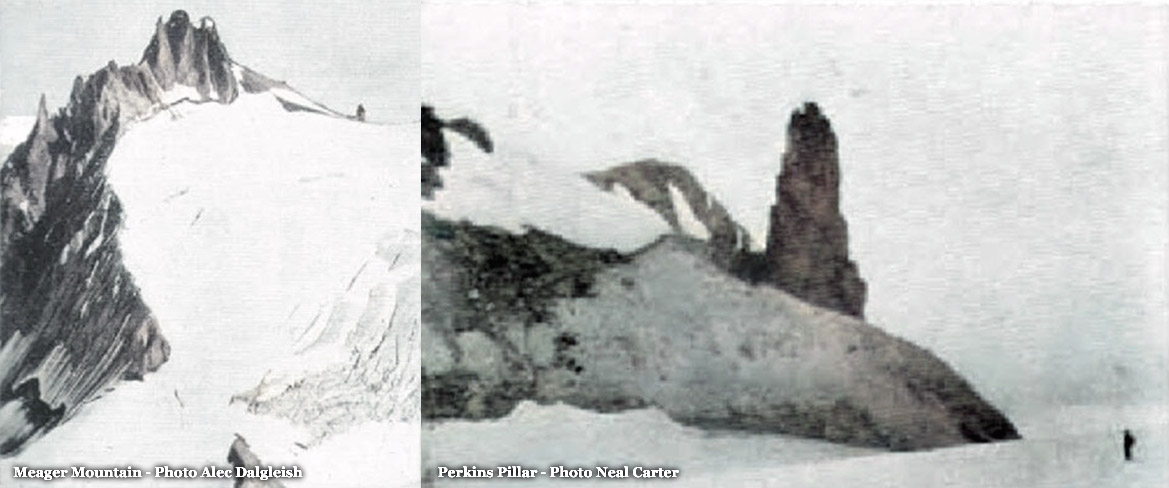

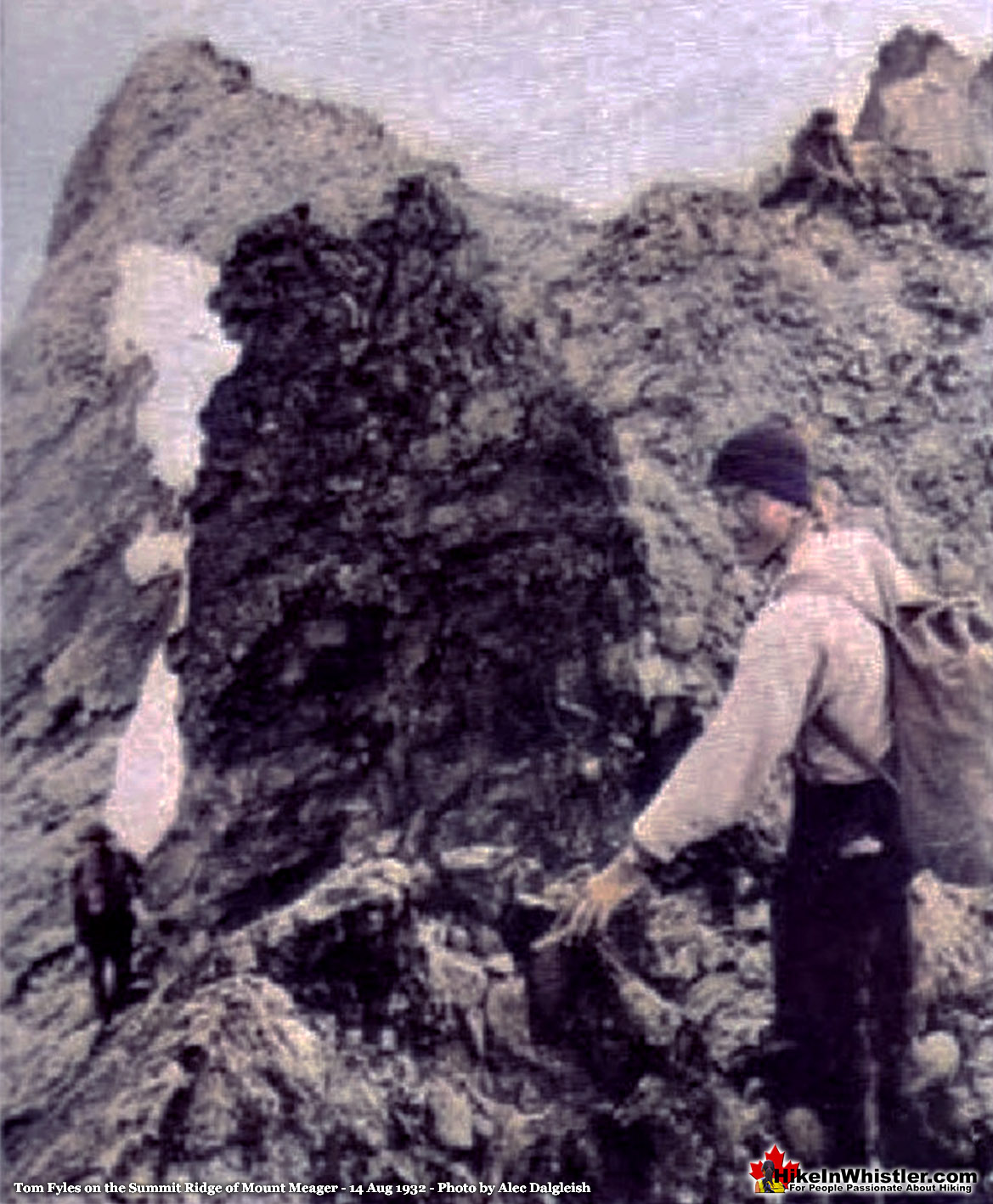

August 14th, 1932 Day 7: Plinth, Perkins Pillar and Meager

August 14th dawned most promisingly and we decided to bag the highest peaks seen close at hand yesterday. Following our return footsteps of the previous evening as far as the base of Mt. Capricorn, we swung to the right and ascended the Capricorn glacier to a peculiar, three-way pass below what we believed to be the aforementioned Meager Mt. This pass, named Triskelion after the device on the Manx coat-of-arms, provided a close up view of a sheer, 400-foot rock pillar which had been observed by different trappers from the Lillooet valley. At Bert’s request its height was triangulated in order to settle a (financial?) argument which appears to have originated between him and some of his pals. “Perkins’ Pillar” seemed a good name.

Meager Mountain & Perkins Pillar - 14 August 1932

Turning now to the supposed Meager Mt., we found its ascent relatively simple except for the last hundred feet. The loose, igneous rock, brightly colored in hues of red and sulphur-yellow, proved most treacherous and we rested on an ashy saddle just below the summit, where a Lapland longspur graced us with its company. An interesting feature of the view from here was an outlier surmounted by two pointed pillars of rock strongly reminiscent of the well-known horns of the dilemma. One of these pillars was pierced by a “window” estimated to be twenty feet high, and which could be readily discerned from the valley below.

Tom Fyles on the Summit Ridge of Mount Meager - 14 August 1932

Fyles and Dalgleish went on to the final, tottering pile of rock which called itself a peak, but seemed hesitant about announcing their victory. They commenced throwing rocks at the blade-like crest of the ridge and triumphant shouts finally re-echoed their success in knocking over the unattainable summit, leaving them on the (now) 8830-foot peak of Meager Mt., one of the few recorded instances of the mountain coming to Mohammed. My effort to establish a camera station on the actual summit was unsuccessful since the necessary cairn would not stay poised. A small gap just below was finally utilized, and by pushing over several projecting masses with an ice-axe, most of the horizon could be photographed. Splendid views of the Lillooet valley and the mountains of the Bridge River district were obtained, but we were still at that edge of our little group farthest removed from the snowy giants to the west and northwest.