![]() Neal Carter (14 Dec 1902 – 15 Mar 1978) was a mountaineer and early explorer of the Coast Mountains primarily in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Highly skilled as a mountaineer, Carter also excelled at cartography and surveying which he used to map the vast unnamed and unexplored mountains of BC. He named a staggering number of mountains, peaks and glaciers as well as making 25 first ascents of mountains, many of which surround what we now call the Whistler Valley.

Neal Carter (14 Dec 1902 – 15 Mar 1978) was a mountaineer and early explorer of the Coast Mountains primarily in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Highly skilled as a mountaineer, Carter also excelled at cartography and surveying which he used to map the vast unnamed and unexplored mountains of BC. He named a staggering number of mountains, peaks and glaciers as well as making 25 first ascents of mountains, many of which surround what we now call the Whistler Valley.

Neal Carter Mountaineer

- Neal Carter Mountaineering Highlights

- First Ascents by Neal Carter

- 1920: Black Tusk North Pinnacle

- 1922: Second Ascent of The Table

- 1923: Carter/Townsend Expedition

- 1932: Mount Meager Expedition

- 1933: To the Cradle of Toba River!

- 1934: Mount Waddington Tragedy

Carter recalled his first impression when he first saw it in 1923, “..the skylines seen from their main valley in which Alpha, Nita, Alta, and Green Lakes lie. Alpine features beyond those skylines were pretty sketchy on maps, and few had names.” A few weeks later he and Charles Townsend would spend two weeks exploring these mountains, nearly all unclimbed, unnamed and very challenging. A skilled mountaineer, surveyor and cartographer, he compiled much of the data that went into the first official topogra

1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

In the summer of 1923 Neal Carter and Charles Townsend went on an incredible two-week climbing expedition around what is now Whistler. They set off from Rainbow Lodge and climbed the previously unclimbed Wedge Mountain. From the summit of Wedge they spotted a mountain to the north in the midst of a maze of glaciers. They named it Mount James Turner and managed its first ascent as well. In the following days they hiked up Singing Pass and to the summit of Overlord Mountain. They made first ascents of two peaks, which they named Diavolo and Whirlwind. Carter left photos at Rainbow Lodge and now they reside in Whistler Museum. Continued here...

1923: Wedge & Whistler Expedition

Neal Carter & Charles Townsend

In the summer of 1923 Neal Carter was working as a surveyor in the valley stretching from Brandywine Falls to Green Lake. This valley wouldn’t be known as Whistler Valley for several more decades. Carter helped cut the first packhorse trail to Cheakamus Lake and hiked up to Whistler Mountain via Singing Pass in order to sketch the shape of Cheakamus Lake. From high up on Whistler Mountain he got a close look at Wedge Mountain, which Alex Philip would later tell him was thought to be unclimbed. Alex Philip was, along with his wife Myrtle Philip, the owners of Rainbow Lodge at Alta Lake. Alex Philip further mentioned that he believed Wedge Mountain to be a higher mountain than Mount Garibaldi. In 1923 Mount Garibaldi was the highest mountain in Garibaldi Park, which at the time extended only as far north as Cheakamus Lake. At the end of the summer with his survey work finished he persuaded Charles Townsend to join him on a two week expedition to climb Wedge Mountain and the mountains beyond.

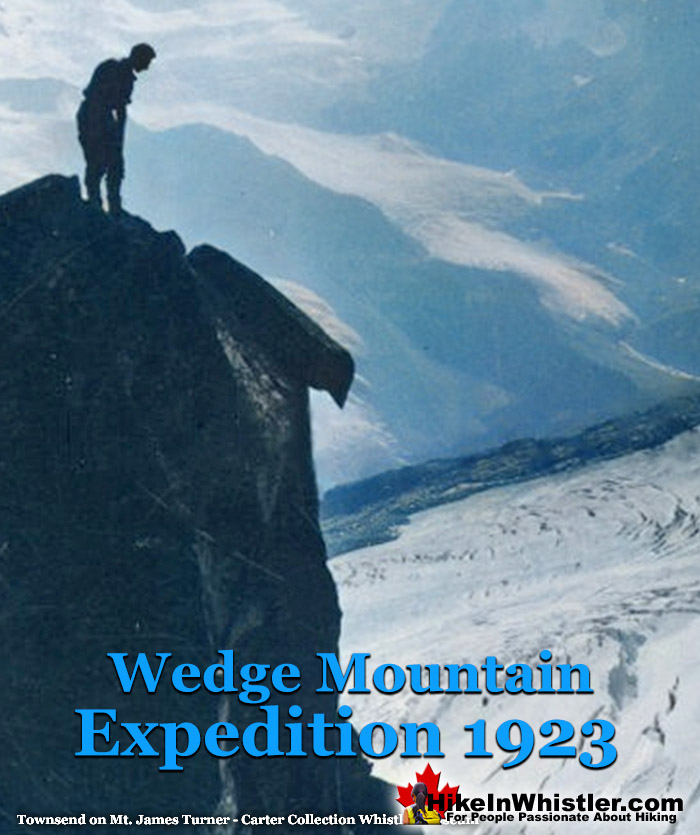

Neal Carter's Article in The Vancouver Sun - 30 Sept 1923

Neal Carter wrote a wonderful article about his two weeks exploring the mostly unclimbed and unnamed mountains around Alta Lake, decades before it became known as Whistler Valley. His article is shown further below in bold. Dates have been added as well as photos he took that were included in this article and several other photos that were not. Some of the original black and white photos have been colourized to enhance their appearance. Wedgemount Creek mentioned several times in the article is now officially named Wedge Creek. Turner Glacier has also been officially renamed as Chaos Glacier.

RUGGED PEAKS ARE CONQUERED IN BC WILDS

By NEAL M. CARTER

While engaged on a survey along the P.G.E. Railway this summer, during which the district between Alpha and Green Lakes, and later, Cheakamus Lake, was traversed, I had occasion to view many fine unclimbed mountain peaks in the unmapped and practically unexplored regions around the heads of the valleys lying to east of the railway, and at the head of Cheakamus Lake. Chief among these was a fine peak well known to visitors at Rainbow Lodge as “Wedge Mountain” from its characteristic shape as viewed from that angle. Looking up Fitzsimmons Creek valley from a few hundred yards beyond the lodge on the railway, another high series of mountains may be seen, the highest of which was climbed this summer by Mr. and Mrs. Don Munday of the BC Mountaineering club while reconnoitring from a proposed site for a summer mountaineering camp. Having to be content while surveying with viewing these peaks from the depths of valleys, I determined to return with a fellow member of the Mountaineering club to investigate them at closer range during a two weeks pleasure trip.

FULLY EQUIPPED

With the main object of making the first climb recorded of Wedge Mountain, Mr. Charles T. Townsend and myself left Vancouver on Saturday morning, September 8, with full equipment to contend with any glacial or rock features we should encounter. This included heavily nailed boots, ice-axes, snow glasses, a rope, etc., as well as an aneroid and mapping facilities to bring back data of our trip. Food, clothing and a tent were chosen such as would keep the backpacking within the limits of a “pleasure” trip. Arriving at Alta Lake, we were in time to have our last civilized meal at Rainbow Lodge before turning in a little way up the track under the stars.

September 9,1923: Alta Lake to Camp #1 on Parkhurst Mountain

Sunday dawned a beautifully clear day, and by 10:30am we had hiked down the track to Mile 42 on Green Lake. Opposite here, a ridge comes down from the shoulder of Wedge around the base of which Wedgemount Creek wends its way through box canyons to join the Green River farther down the railway. So, turning our faces to the east, we struck into the timber and after a brief lunch of hard tack, chocolate and cheese, crossed Wedgemount Creek on a slippery log and commenced the real climbing.

Neal Carter Crossing Wedge Creek - 9 Sept 1923

OBSTACLES ENCOUNTERED

All through the hot afternoon, a tiresome series of hollows, ridges and rocky bluffs was encountered; sometimes treading on a mossy carpet, no pushing our way through dense tangles of blueberry bushes, then perhaps scrambling up some stony cliff. Without so much as a glimpse of our mountain all the way, and only one drink of water, we were heartily glad to come out at timberline about 6 o’clock and find ourselves withing an easy day’s journey of the peak. Another hour was spent in searching for water, which was eventually founded trickling from under a small ice sheet. Here we pitched our tent.

Neal Carter at Camp #1 Wedge Mountain in Background

September 10, 1923: Wedge Mountain

The weather on the 10th was fine, the aneroid stationary at 5800 feet, so we left camp in the morning for the final climb on Wedge Mountain in fine spirits.

Wedge Mountain from Ridge Above Camp - 10 Sept 1923

Continuing up the ridge leading towards the mountain, an unavoidable gap forced us to cross mountainous remains of some huge glacier of the past, and it was after 11am before we reached the base of the final 2000-foot slope of broken, jagged chunks of rock that form the face of which looks so perpendicular from Alta Lake. This really was at an angle of about 40 degrees though steeper in places where the bedrock was exposed almost perpendicularly.

West Face of Wedge Mountain - 10 Sept 1923

No especial care or skill was needed in the final ascent except to prevent the foot being caught when three or four 500-pound rocks would shift and settle when stepped on.

Charles Townsend Climbing Wedge Mountain - 10 Sept 1923

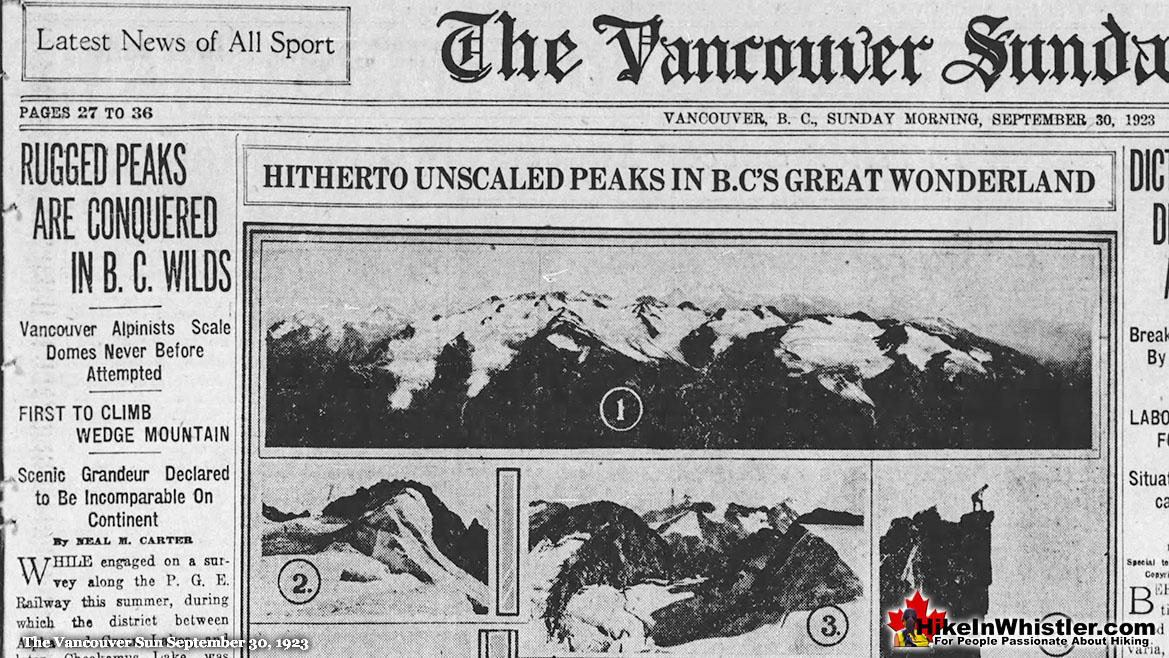

SAW SUN’S ECLIPSE

A summit ridge of elevation 8200 feet was finally reached, culminating in the actual peak, some 200 feet higher at the far end. A splendid view of the partial eclipse of the sun was obtained just before reaching here.

Neal Carter on Wedge Summit Ridge - 10 Sept 1923

Neal Carter Wedge Mountain Summit - 10 Sept 1923

First View of Mt James Turner from Wedge Summit - 10 Sept 1923

Panorama South from Wedge Mountain - 10 Sept 1923

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Wedge Mountain

In 2012, Jeff Slack, working at the Whistler Museum created three wonderful videos of the Carter/Townsend expedition. He used the written account of Charles Townsend and the photos taken by Neal Carter. He narrated the videos along with images from Google Earth, recreating the journey in beautiful detail. This is the first of the three videos, The 1st Ascent of Wedge Mountain - A Virtual Tour, which covers the journey from Rainbow Lodge to the summit of Wedge Mountain.

September 11, 1923: Hike Around Wedge to Camp #2

Following around the face of Wedge, keeping approximately at timberline all the way, we came to the edge of the deep valley behind Wedge and dropped down 800 feet to camp beside a roaring stream coming from a glacier not far above us. A long hot walk along a steep side hill all afternoon with little or no water again made us thankful to lay out the sleeping bag on the heather and play ourselves to sleep.

Carter Looking West to Wedge Mountain - 12 Sept 1923

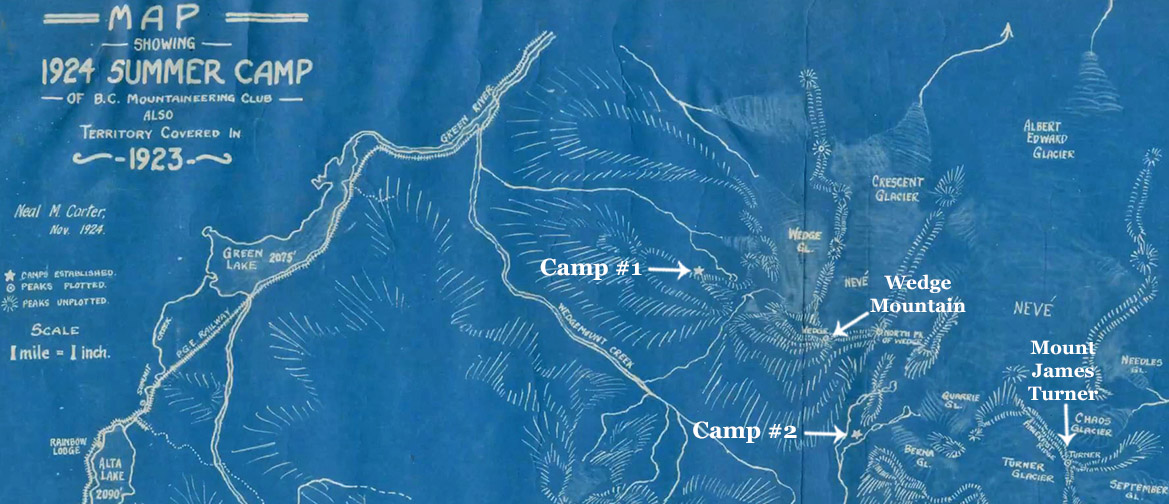

Section of Neal Carter's 1924 Map

In 1924 Neal Carter created the first detailed map of the region that would become Garibaldi Park. His contribution to mapping and surveying the region was enormous and the original Garibaldi Park topographical map created in 1928 was largely based on his exploration and surveying work. This is a small section of his 1924 map showing some details of the 1923 expedition. To make it easier to identify, Wedge Mountain and Mount James Turner have been added to highlight their location on the map. Also Camp #1 and Camp #2 have been added. They are shown on the map as stars. Camp #1 was on Parkhurst Mountain, which was unnamed at the time, which is why Carter and Townsend never identify it. It is interesting to note that Carter's map does not show Wedgemount Lake, which evidently covered by Wedgemount Glacier at the time.

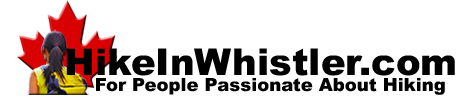

September 12, 1923: Mount James Turner

The summit was finally reached safely about 2pm, and found to consist of a pinnacle of rock hardly large enough to stand on. The mountain is shaped like a tetrahedron, two of whose faces are precipitous and hopeless to climb; the third, up which we came, only slightly less so.

Neal Carter on Mount James Turner - 12 Sept 1923

DEPOSITED RECORD

As large a cairn was built as the peak would support, and a record deposited naming it Mt. Turner, after the Rev. James Turner, a lifelong Methodist church worker who died in 1916 at the age of 74 after rendering many years of faithful service in this province and the Yukon.

Neal Carter Mount James Turner Summit - 12 Sept 1923

The elevation proved to be 8000 feet, and the large glacier we had crossed was named the Turner Glacier. (Turner Glacier is now called Chaos Glacier)

Neal Carter Chaos Glacier & Fingerpost Ridge - 12 Sept 1923

Another huge glacier to the north having a neve of over 8 square miles, we named the Albert Edward. Several others were named, on in particular, consisting solely of one continuous ice-fall, became the Needle Glacier from its numerous ice pinnacles.

September 13, 1923: Camp #2 to Camp #1

Carter skips September 13th in his article, as it was just a move from their second camp back to their first camp on Parkhurst Mountain.

September 14, 1923: Camp #1 to Alta Lake

Carter also doesn't write about September 14th where they hiked down to the Rainbow Lodge for the night. Townsend wrote about the day briefly in his Mountaineer article: "The next day we packed back to our first camp and the day following down to Alta Lake. The latter journey taking six hours. At Rainbow Lodge we had an excellent supper which partially made up for a week of dried goods. Afterwards we collected the other half of our grub preparatory to making an early start the next day up Fitzsimmons Creek."

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Mount James Turner

This is the second of three videos created by Jeff Slack for the Whistler Museum. This one titled, The 1st Ascent of Mount James Turner - Virtual Tour, shows the journey Carter and Townsend went on to reach Mount James Turner. Using Google Earth, Slack follows the route they took, narrates the journey with Townsend's written account, and illustrates it with Neal Carter's beautiful photos.

September 15, 1923: Alta Lake to Fitzsimmons Cabin

Carter's article doesn't include details about their hike up Whistler Mountain on the 15th. Charles Townsend wrote a short description of the day in his BC Mountaineer article: "The following morning, we left Rainbow Lodge at 11am and found the trail up Fitzsimmons Creek was excellent to travel on. But for some exciting moments with wasp nests, we had an enjoyable day's journey to the cabin on the meadows below Avalanche Pass. The two miners we found to be not at home so we made ourselves comfortable in their absence."

September 16, 1923: The Fissile, Refuse Pinnacle and Overlord

On Sunday we made the ascent of Mt. Overlord, second highest in the group, by way of going around the rear of Red Mountain and over a series of pinnacles on the ridge leading up to Mt. Overlord.

Neal Carter on Pinnacles Leading to Overlord - 16 Sept 1923

One in particular on one side was a sheer drop to the Fitzsimmons Glacier hundreds of feet below, while the back was a veritable ore-dump consisting of strips of granite, quartz, slate, iron ore, etc., all broken up into small pieces by the frosts and left in a pile at the “clinging angle”. This we refer to as “Refuse Pinnacle”.

Charles Townsend on Refuse Pinnacle - 16 Sept 1923

Mt. Overlord’s summit closely resembles that of Wedge, and is perhaps a little over 8000 feet. Mr. and Mrs. Munday’s record was found, and ours added to it. The view to the north and south is not so striking.

Peaks from Overlord Looking Northeast - 16 Sept 1923

RETURN IS SIMPLIFIED

After climbing a few odd-shaped pinnacles around the rim of the glacier on Overlord, the return trip was simplified by going around the bottom of the pinnacles beyond Refuse Pinnacle on the glacial neve.

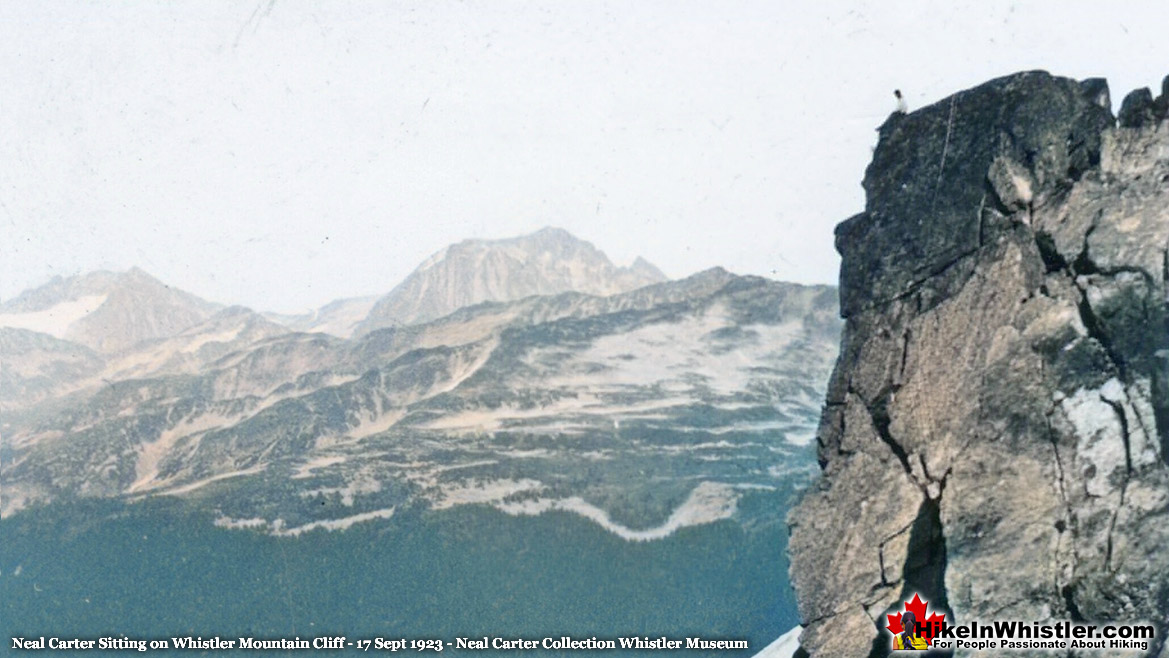

September 17, 1923: Whistler Mountain

Although not a strenuous trip, we decided to take the next day easy and made an ascent of Whistler Mt. from the cabin. This is most easily reached from Alta Lake, which it overlooks, and is frequently ascended from the lodge, and made a pleasant afternoon’s trip..

Neal Carter Whistler Mountain - 17 Sept 1923

September 18, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin to Mount Diavolo

Tuesday the weather showed signs of breaking and we hurried to get in our last trip. From K.M. pinnacle back of Mt. Overlord, I had seen a sharp peak connected to where I was by a knife-edge ice ridge above which a rock arete led to the summit. This was so narrow that sections of it looked as if they could be pushed over, and promised so interesting a climb that Mr. Townsend named it Mr. Diavolo from its black and sinister appearance, and we determined to try this peak today.

CLIMBING IN DANGER

Taking advantage of a momentary rift, a photo was taken and a start made immediately, ice steps had to be cut up the steep ice ridge and when within four steps from the top, my ice-axe cracked and almost broke in two while cutting, very nearly throwing me off my balance and providing rapid transit to the Diavolo Glacier far below. Finishing these few steps with Mr. Townsend’s axe, we stepped onto the rock and began one of the most exciting bits of rock climbing. It is best compared with the summit arete of Mt. Tupper in the Selkirks. Fog hid from us the full extent of the tremendous drops on either side in case a hand or foothold should give away. Fifty minutes later the top of the arete was reached, after a climb of only two or three hundred feet.

Charles Townsend on Ridge to Diavolo Peak - 18 Sept 1923

Here we were much disappointed to find the real summit, a few feet higher, some 50 feet away, connected by a practically level series of knife-edged pinnacles of rock. After some debate in which the lateness of the hour entered into consideration, I started off to work my way along astraddle the ridge, the only indication of Mr. Townsend’s presence behind being a clatter of rocks back in the fog as sections of the ridge would topple over and go avalanching down to the glaciers on either side below. Loosened by me while testing them, he would knock them over to avoid trouble on the return. The summit cairn was finally erected at 2:45 and the name Diavolo heartily verified. Although only 7700 feet in elevation, it amply repaid our search for a rock climb.

Charles Townsend Straddling Diavolo Summit - 18 Sept 1923

On a clear day a wonderful panorama of the mountains around the head of the Pitt River might be obtained, as well as the Cheakamus Glacier, the largest in the region, consisting of one continuous ice-fall from the base of Mt. Castle Towers to almost the level of Cheakamus Lake, 4000 feet below. With the aid of the rope, we negotiated the return safely, and following our footsteps over the fog covered glaciers, made good time by reaching the cabin about 6:30. Soon after in commenced to rain, and the following day was spent inside.

September 19, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin Rain Turned to Snow

We saved food by laying in bed most of the morning reading; however, by night we had almost come to the stage of hiding our food from each other, and if a raisin dropped on the floor, it was a case of get a candle and hunt for it. Snow began to fall in the afternoon, and we awoke next morning to find 2 ½ inches had fallen and part of our firewood, cut in five-inch lengths, packed away under the bed by packrats.

Charles Townsend Outside Fitzsimmons Creek Cabin - 19 Sept 1923

September 20, 1923: Fitzsimmons Cabin to Alta Lake

So we took the hint and after a somewhat imaginary breakfast, left for Alta Lake. That night we had a real supper at the lodge and after a few hours sleep, caught the early morning train (21 Sept Friday) and arrived back in Vancouver at 10:30 am highly pleased with our mountaineering holiday. Lots of goat tracks seen, but few evidences of bear. Only animals actually seen were marmots and a porcupine at the cabin.

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Mount Diavolo

This is the third of three videos created by Jeff Slack for the Whistler Museum depicting the amazing journey Carter and Townsend went on when they explored the Fitzsimmons Valley to the peaks of Mount Overlord. This one is titled, The 1st Ascent of Mount Diavolo - A Virtual Tour. Using the words of Charles Townsend and the photos of Neal Carter, the video shows the journey with the use of Google Earth.

Charles Townsend's Account of the Expedition

Charles Townsend also wrote about the expedition in two articles that appeared in two editions of the BCMC Newsletter in 1923. The October edition printed, 'Trip to Wedge Mountain and Mt. Turner', and in November, 'Fitzsimmons Creek Mountains'. They, along with more of Neal Carter's photos can be found here. The wonderful videos above from the Whistler Museum are narrated directly from Townsend's articles.

Charles Townsend's 1923 BC Mountaineer Articles

BCMC Newsletter October 1923

TRIP TO WEDGE MOUNTAIN AND MT. TURNER

By Chas. T. Townsend

Mr. Neal Carter and I had been planning all the summer to make the first ascent of Wedge Mt. as soon as we could get away in the fall. Accordingly on Saturday evening, September 8th, we landed with our belongings at Alta Lake. Having nearly a fortnight before us, we decided to make Rainbow Lodge our headquarters, and to make two trips, one up Wedge Mountain, and the other to Avalanche Pass, the proposed 1923 camp site.

September 9,1923: Alta Lake to Camp #1 on Parkhurst Mountain

We left half our grub at the Lodge, and with the other half and the rest of our belongings, started out from Alta Lake on Sunday morning bound for Wedge Mountain. We followed the railway for 4 miles to Mile 42, as from Rainbow Lodge we could see that the main ridge from Wedge Mountain hit the railway at about this point. From the railway we travelled east following logging roads for about a mile, and after that picking our way through the trees (there was very little bush), for another half-mile until we reached Wedgemount Creek, where we had lunch. Our journey so far had taken us 3 hours. Wedgemount Creek was larger than we had expected, and we were lucky in finding a log on which to cross quite a short distance above where we struck the creek.

Neal Carter Wedge Creek Log Crossing 9 Sept 1923

On the east side, the hill rises very sharply from the water for about 800 feet, and as the bush was thick, we were very glad of a rest when we reached the top. From there on, the ridge is a succession of bluffs, thickly wooded.

First Glimpse of Wedge Mountain 9 Sept 1923

At about 5,000 feet elevation the trees thinned out, giving place to meadows, which must have been beautiful when the flowers were in bloom. We were nearly “all in” when we found water at about 6 pm, and we made camp as quickly as possible. We were now in an ideal place for an attempt on Wedge Mountain, being at an elevation of 6,000 feet, and at the extreme limit of timber line.

September 10, 1923: Wedge Mountain

Early the next morning we started up the ridge. At the end of it we found quite a gap in between us and the base of the mountain, and I should suggest to any others who might make the climb, that it would be more advisable to keep on the south side of the ridge at an elevation of about 6,000 feet, instead of climbing to the top of it. This would bring them to the foot of the gap and at the base of the easiest face of Wedge Mountain.

Wedge Mountain from Ridge Above Camp 10 Sept 1923

As it was, we had to descend into the gap, cross a number of ridges composed of masses of loose rocks, probably moraines at one time, and then cross a small glacier, before we got on to the climbable slopes of the mountain. The glacier we named “Eclipse Glacier.”

Charles Townsend Eclipse Glacier 10 Sept 1923

From there to the peak, about 2000 feet, we were travelling over talus slopes, the rocks being on an average cubes about 2 feet in thickness. We reached the summit at 115, after having had a good view of a partial eclipse of the sun a short time before.

Charles Townsend West Face Wedge Mountain 10 Sept 1923

Charles Townsend Wedge Summit Looking East 10 Sept 1923

The summit of the Mountain is a long ridge ending in quite a sharp peak at the eastern end. It is very precipitous on three sides, but is readily accessible on the south side, up which we had come.

Charles Townsend Wedge Mountain First Ascent 10 Sept 1923

Owing to the clearness of the atmosphere, we had a magnificent view, and were able to secure some fine photographs. Immediately to the south of us was the Spearhead Range, which has been practically unexplored. It contains seven fine glaciers on the north side, and, as we afterwards discovered, one on the south side. What particularly attracted us was a valley immediately south of the peak of Wedge Mountain. This valley pointed north and south, and contains beautiful meadows. At the head of it, on three sides, there are three large glaciers, one of which has a splendid ice-fall. The meadows are probably at an elevation of about 5,500 feet, and they lie in the centre of the Spearhead Range, so that a party intending to climb in that district would do well to investigate the possibilities of a camp there. We named the place “Glacier Meadows.” It would also seem to be possible to climb peaks in the Fitzsimmons district from there, as there is quite a low pass over to the Fitzsimmons Valley. Mt. Overlord, and a number of other peaks at the head of the Fitzsimmons glacier, possibly could be climbed in a day's trip.

Panorama South from Wedge Mountain 10 Sept 1923

On the north side of Wedge Mountain are several large glaciers, one of which we called “Wedge Glacier,” and another the “Crescent Glacier.” To the east of us lay a peak which we resolved should be the object of our next climb. It lay across a valley from Wedge Mountain, and promised to be an enjoyable three-day trip from camp.

First View of Mt James Turner from Summit of Wedge Mountain 10 Sept 1923

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Wedge Mountain

In 2012, Jeff Slack, working at the Whistler Museum created three wonderful videos of the Carter/Townsend expedition. He used the written account of Charles Townsend and the photos taken by Neal Carter. He narrated the videos along with images from Google Earth, recreating the journey in beautiful detail. This is the first of the three videos, The 1st Ascent of Wedge Mountain - A Virtual Tour, which covers the journey from Rainbow Lodge to the summit of Wedge Mountain.

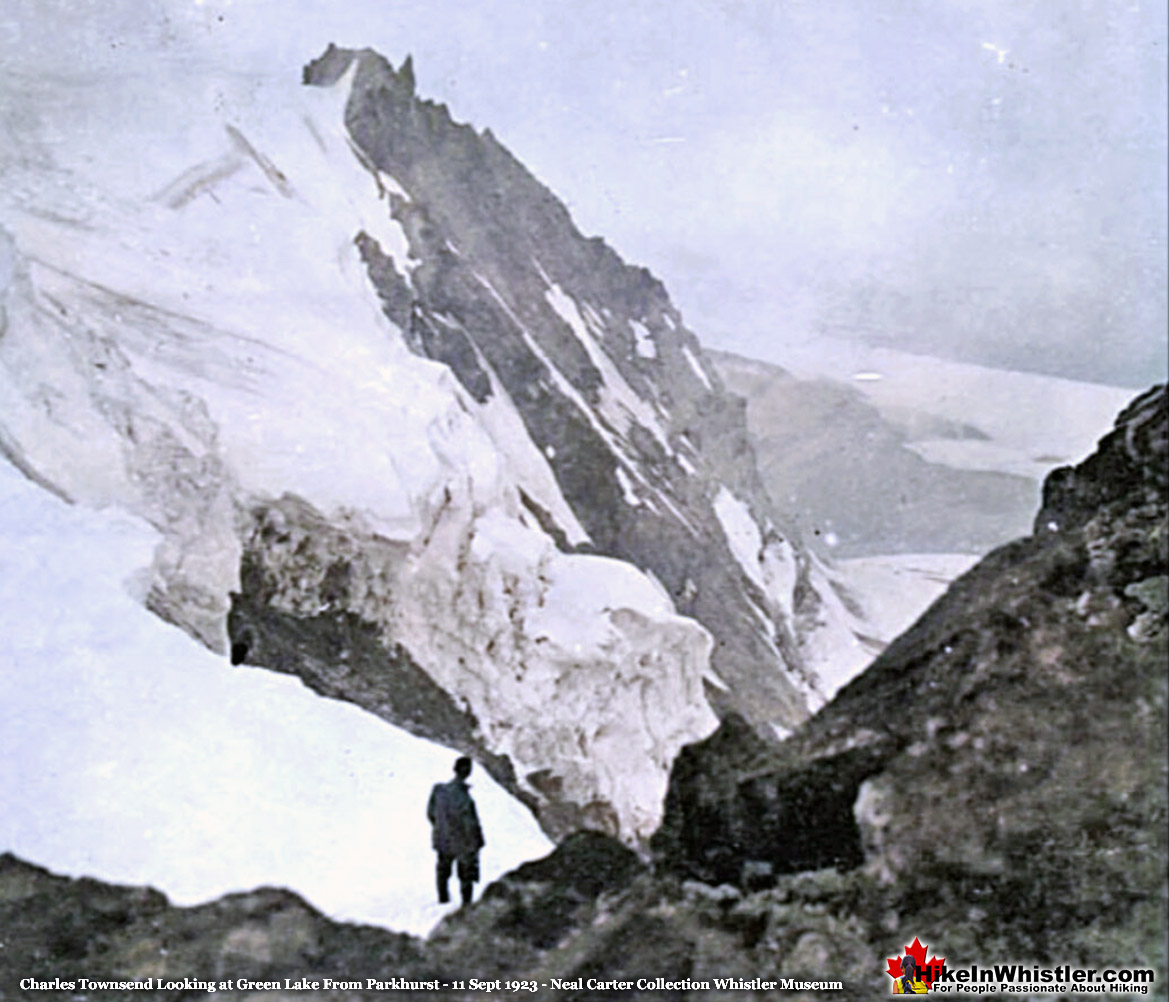

September 11, 1923: Hike Around Wedge to Camp #2

The next day, taking with us just enough food for three days and our bedding, and leaving our tent behind, we hiked round the southern slopes of Wedge Mountain, keeping just above timber line to avoid the bush.

Neal Carter About to Leave Camp 11 Sept 1923

Charles Townsend Looking at Green Lake from Above Parkhurst Camp 11 Sept 1923

To obtain water we had to drop down about 800 feet into the valley east of Wedge Mountain, which we had seen the day before, where we found a delightful camping spot. The journey from camp to camp took us about 5 hours. We lulled ourselves to sleep under the stars that night with soothing strains from the camp orchestra.

September 12, 1923: Mount James Turner

The first part of our climb the next day took us over four high ridges, very much similar in composition to Wedge Mountain. This brought us to an elevation of about 7.000 feet, where we came out on to a glacier which we called the “Quarry Glacier” From there we had a good view of the peak of Mt. Turner, as Neal had named it, in memory of the Rev. Jas. Turner. Once across the Quarry Glacier, we had to cross the Turner Glacier, much larger than the former, and flowing east, while the other flowed west towards Wedge Mountain.

Neal Carter on Turner Glacier (now Chaos Glacier) 12 Sept 1923

We were now at the foot of the cliffs at the base of the peak. These cliffs run east and west from the base of the peak; on the west side they form a striking ridge of jagged rock surmounted by fantastic pinnacles. Owing to this peculiarity we called it “Finger-post Ridge” We had some trouble getting up the cliffs to the east of the peak owing to the extreme looseness of the rocks, but once on top, we were ready for the final climb. The peak is a mass of jagged rock, most of which is very loose and dangerous, and I doubt whether it could be climbed from any direction other than the east. An hour's rock-climbing took us to the summit, where we arrived at 1:30. The top itself was so small that it was hardly big enough for a cairn. On three sides the cliffs were very precipitous, while even the face up which we had come looked very steep from above.

Charles Townsend James Turner Summit 12 Sept 1923

Once again we had a magnificent view, particularly of Wedge Mountain, which looks very fine from that side. Three glaciers to the north we named respectively, “The Chaos,” “The Needle,” and “The Albert Edward” glaciers.

Charles Townsend Mount James Turner 12 Sept 1923

We reached camp again at about 6 p.m.

September 13, 1923: Camp #2 to Camp #1

Townsend does not write about September 13th which was spent moving from their second camp to their first camp on Parkhurst Mountain.

September 14, 1923: Camp #1 to Alta Lake

The next day we packed back to our first camp, and the day following down to Alta Lake, the latter journey taking us six hours. Our aneroid was found to be untrustworthy, so we had to estimate our elevations from well-known peaks in the Garibaldi district. Thus we made Wedge Mountain to be 8,400 feet high, or higher than Castle Towers, and Mt. Turner to be 8,000 feet, or 400 feet lower than Wedge Mountain. At Rainbow Lodge we had an excellent supper, which partially made up for a week of dried goods, and afterwards collected the other half of our grub preparatory to making an early start the next day up Fitzsimmons Creek.

Whistler Museum's Virtual First Ascent of Mount James Turner

This is the second of three videos created by Jeff Slack for the Whistler Museum. This one titled, The 1st Ascent of Mount James Turner - Virtual Tour, shows the journey Carter and Townsend went on to reach Mount James Turner. Using Google Earth, Slack follows the route they took, narrates the journey with Townsend's written account, and illustrates it with Neal Carter's beautiful photos.